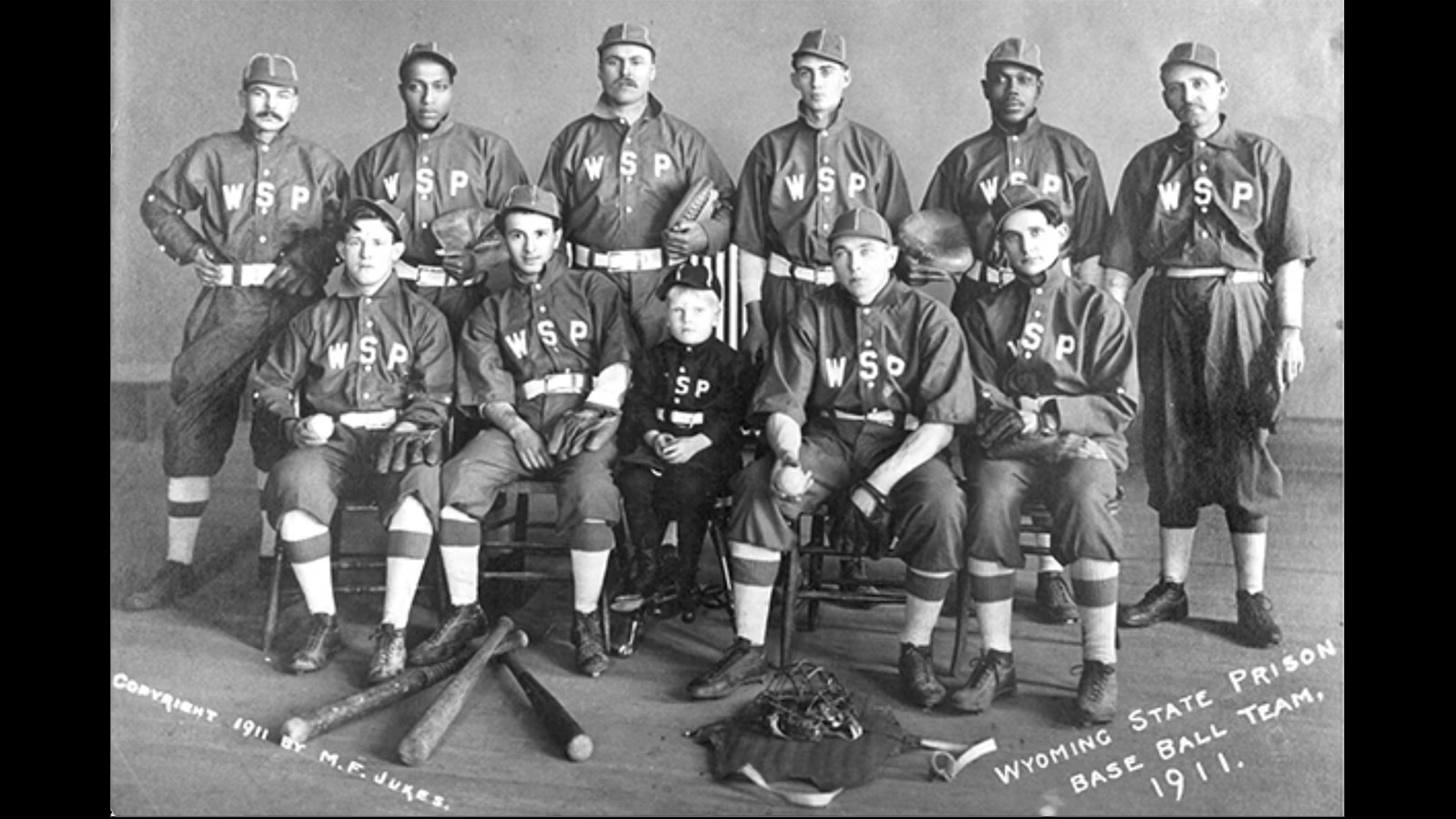

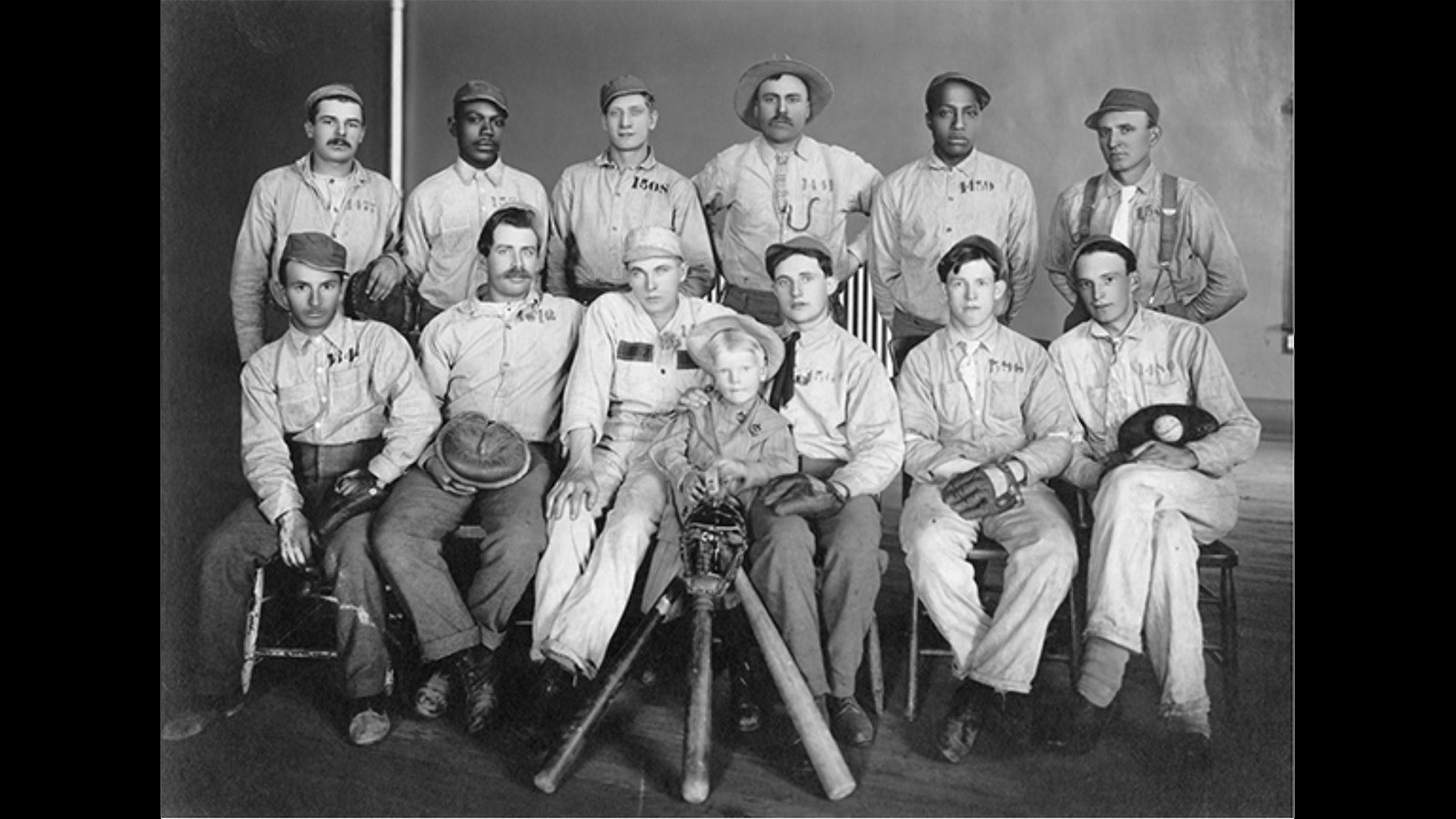

As baseball teams go, the Wyoming State Penitentiary All-Stars looked a lot like any other from the era. A team photo from their 1911 season shows a sharp-looking ball club decked out in spiffy uniforms, matching caps, gloves and bats proudly displayed.

Closer examination reveals a darker side.

The lineup included a murderer at shortstop, a burglar at third and manning first base was a convicted rapist. If that’s not enough, the team’s star player in right field had a date with the hangman before the season was scheduled to end.

It sounds like a twisted version of the old Abbott & Costello comedy routine “Who’s On First?” Call it “Field of Nightmares.” Never mind the 1927 Yankees, this was the original “Murderers’ Row.”

It’s hard to believe, but this tale is 100% true. A team of prison convicts made up one of Wyoming’s better baseball teams in 1911. What’s more, there is every reason to believe they were literally playing for their lives.

Bases Loaded

The Wyoming State Penitentiary All-Stars was a baseball team made up of convicts who showed some aptitude for the sport.

On the surface, it was one of the more novel prison programs instituted by a newly installed warden who cherished the game. At its ugliest, it may have fostered the same kind of corruption that the previous warden had been accused of.

This story comes at a time in American history when the popularity of baseball was beginning to sweep the nation. At the turn of the century, the sport of baseball was becoming all the rage. Every kid wanted to be like Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson. Men followed daily box scores religiously.

In Wyoming, baseball fever was catching on as well. Semi-pro and amateur teams were sprouting up everywhere. Edward Meeker’s 1908 hit “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” was still getting airplay on home radio sets.

Fans in the Cowboy State couldn’t get enough of the game.

This preoccupation with America’s pastime helped pave the way for the WSP All-Stars, but the catalyst was far more ominous in nature.

Early Days At The State Pen

Opened for business in 1901, the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Rawlins was the kind of gloomy lockup that made criminals almost wish for the rope. No running water or electricity, it was a cold, dark and miserable place to be incarcerated.

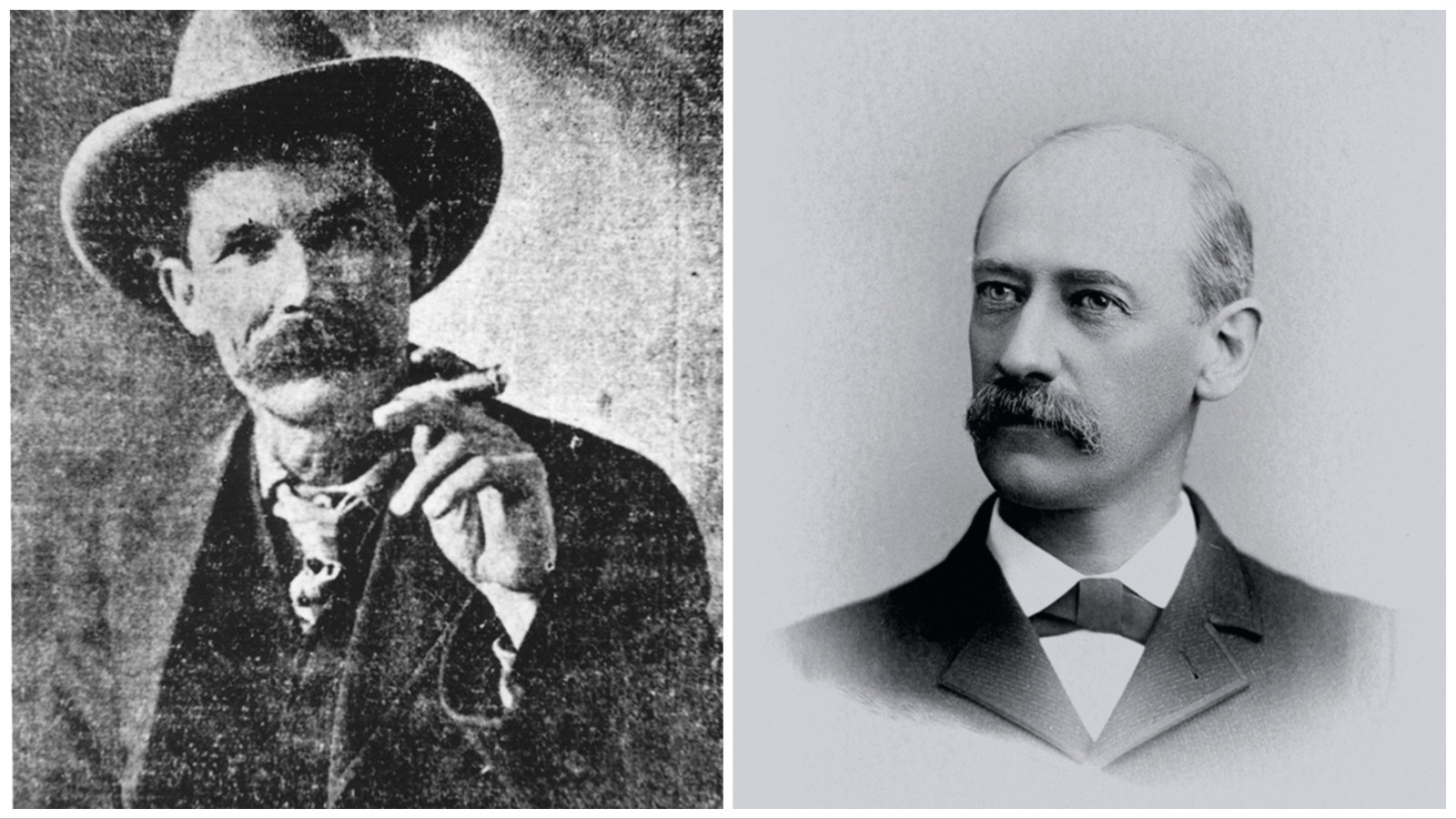

To make matters worse, millionaire businessman Otto Gramm practically ran the prison with assistance from the actual warden, JP Hehn. Under a penitentiary lessee program popularized in the South and instituted elsewhere in the nation, inmates were put to work for Gramm manufacturing brooms in a makeshift prison factory for 57 cents a day.

Prisoner grunts were often mistreated and barely fed enough to stay alive while Gramm benefitted from an average of 60 dozen brooms per day produced by his conscripted workforce from among the 200 inmates at the Wyoming State Penitentiary.

It was “a system of the dark ages,” said one inmate, Harry Pendergraft, who was in for larceny.

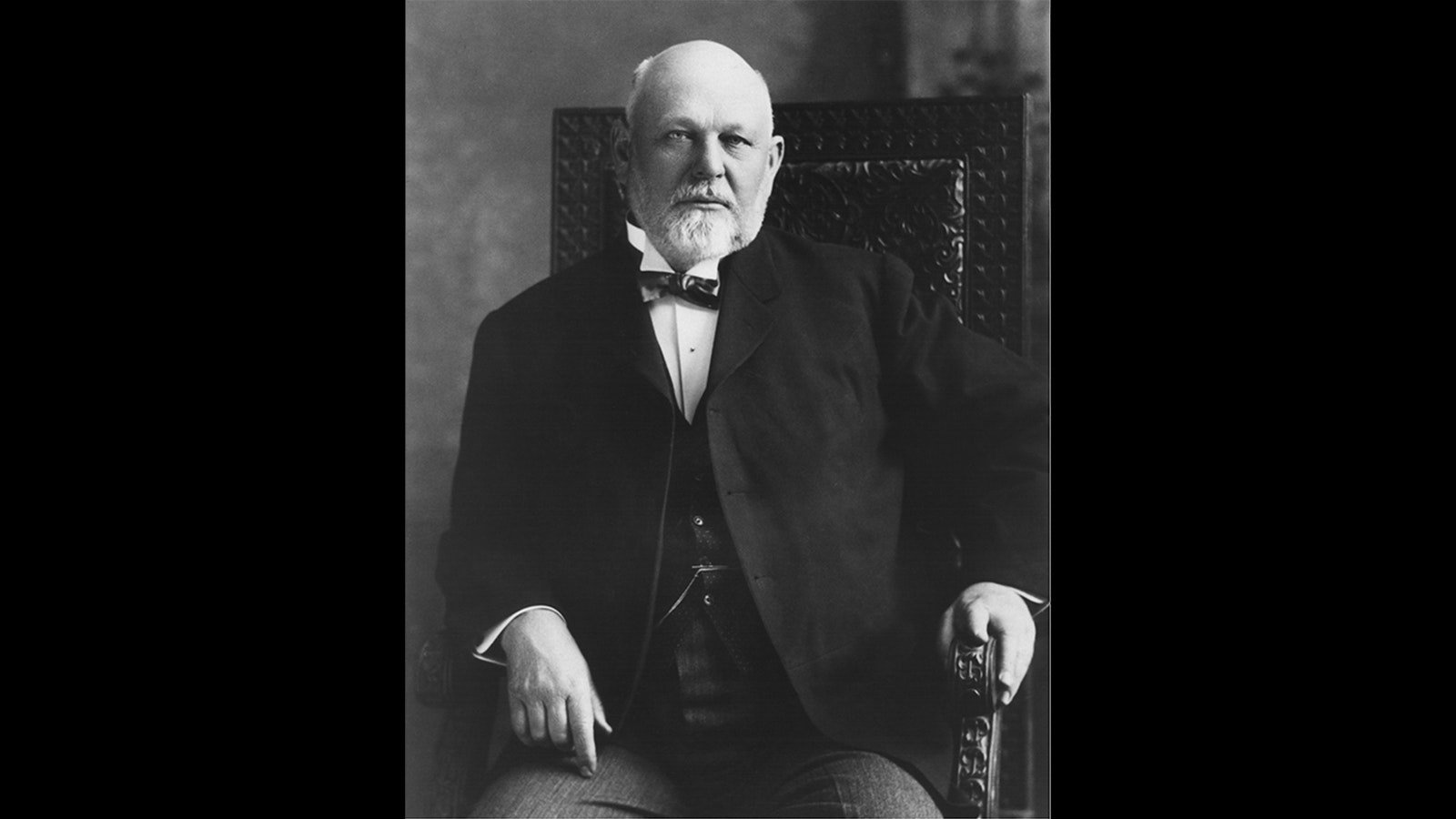

After more than a decade in operation, Gov. Joseph Carey shut the program down in 1911 and cleaned house. The governor tapped Big Horn County Sheriff Felix Alston as the new warden and the scene was set for wide-sweeping prison reform.

No change was bigger than the assembling of the institution’s first baseball team.

Bad News Bears

A huge baseball fan, Alston thought a prison team could boost spirits amongst the inmate-players and build moral at the prison across the board. What he didn’t count on was just how good a team he would assemble.

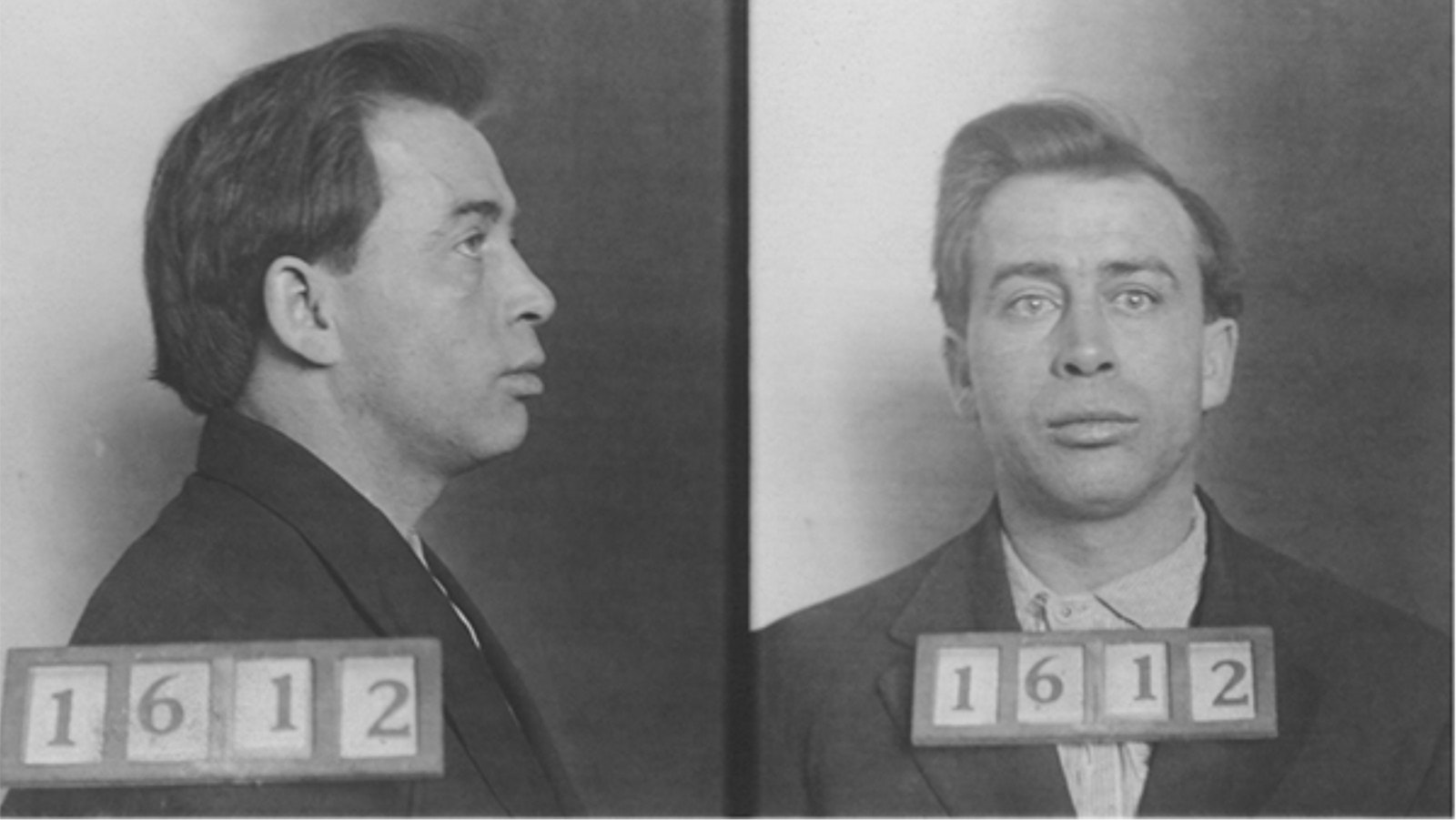

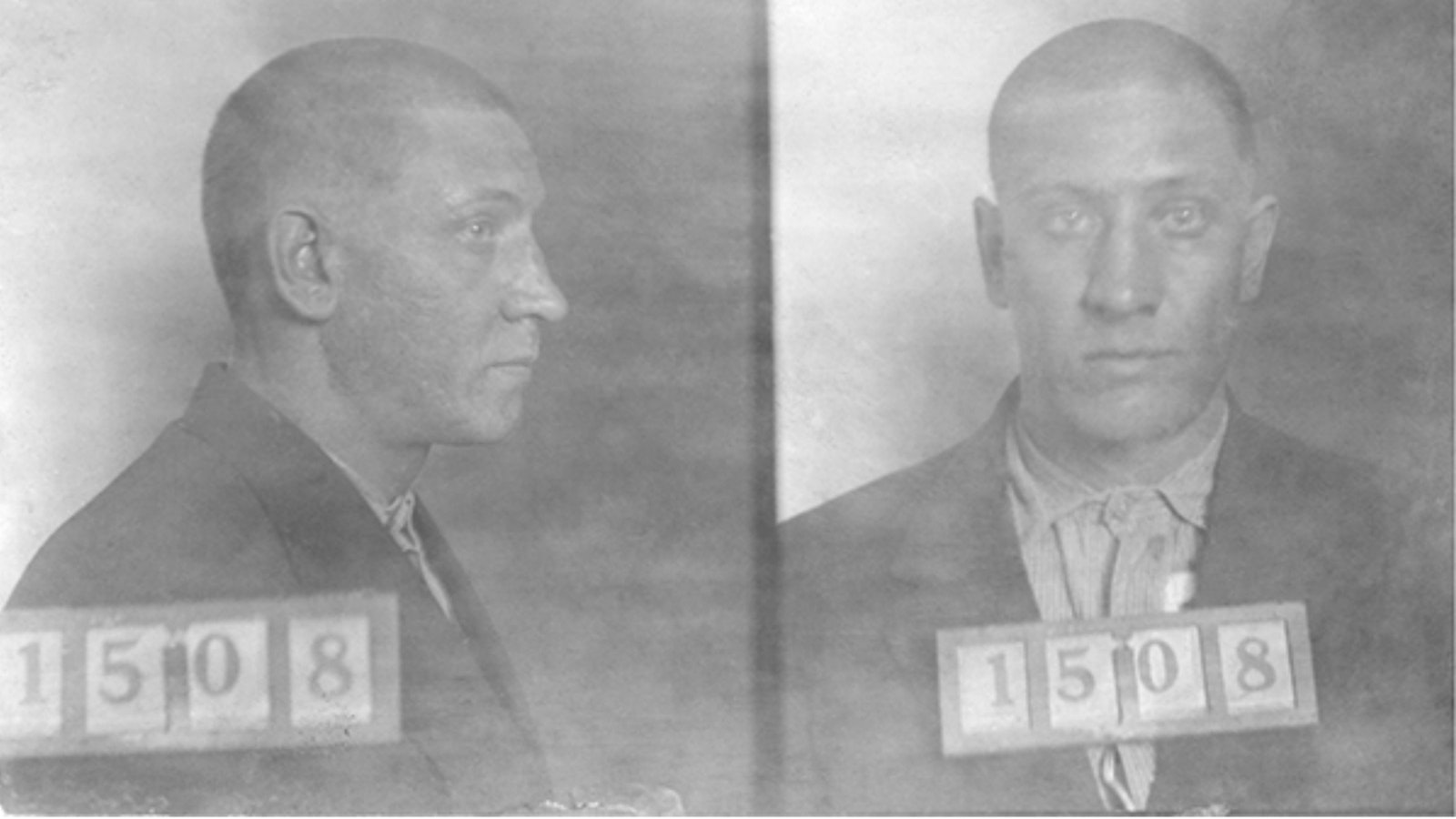

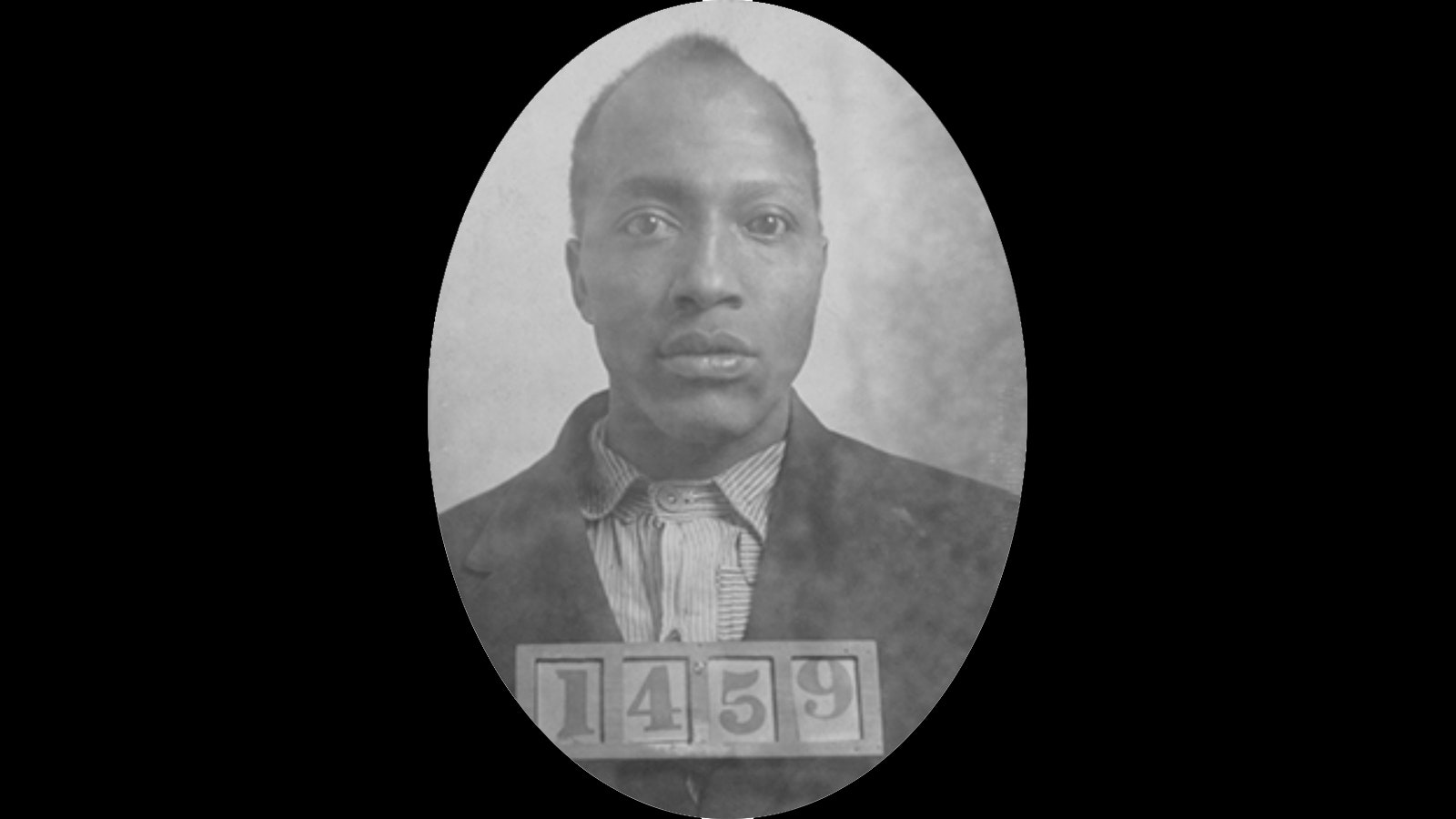

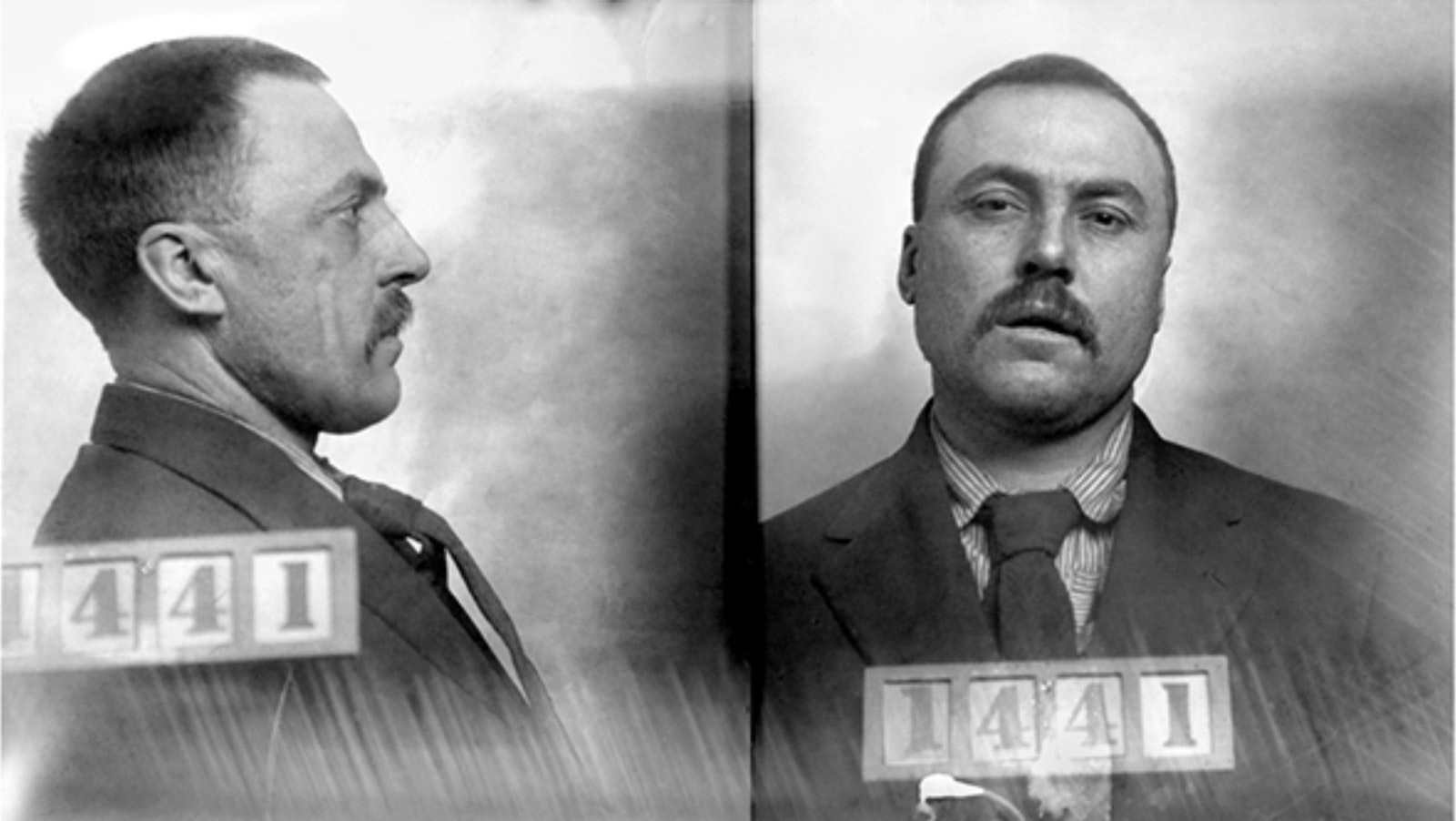

Ranging from ages 18 to 39, the inmate All-Stars roster was fleshed out by the likes of shortstop Joe Guzzardo (manslaughter), first baseman Eugene Rowan (rape), third baseman John Crottie (grand larceny), center fielder Sidney Potter (forgery), second baseman Frank Fitzgerald (breaking and entering) and right fielder Joseph Seng (first-degree murder).

Ace pitcher Thomas Cameron, 20, was a coal miner from Tennessee with an explosive fastball and a rap sheet that included sexual assault.

The team’s coach was stone cold killer George Saban, doing a 25-year stretch for shooting a sheepherder in the face and killing and burning two others during the Spring Creek raid — the ongoing range wars of Wyoming pitting cattlemen against perceived infringements on open grazing.

As bad and this team looked on paper, they were actually pretty good on the diamond, especially Seng (more on his story later).

Opening Day

Daniel C. Kinneman, owner of the Rawlins-based Wyoming Supply Co., suggested to Alston that the convicts play his company team, the Juniors, in a series of games that summer.

Kinneman’s building, plumbing and supply company had a contract with the state penitentiary, so he knew of the new inmate team. He also was interested in seeing how his own ball club, a collection of promising rookies with a few seasoned veterans from the Rawlins city team sprinkled in, might fair against the cons.

The Wyoming State Penitentiary All-Stars played their first game on a cloudless day July 18, 1911. The same day Seng was granted a stay of execution by the Wyoming Supreme Court while his appeal was heard.

Seng celebrated by smacking two home runs as the “Cons” defeated the Juniors 11-1 in a rout played at the stockades on prison grounds.

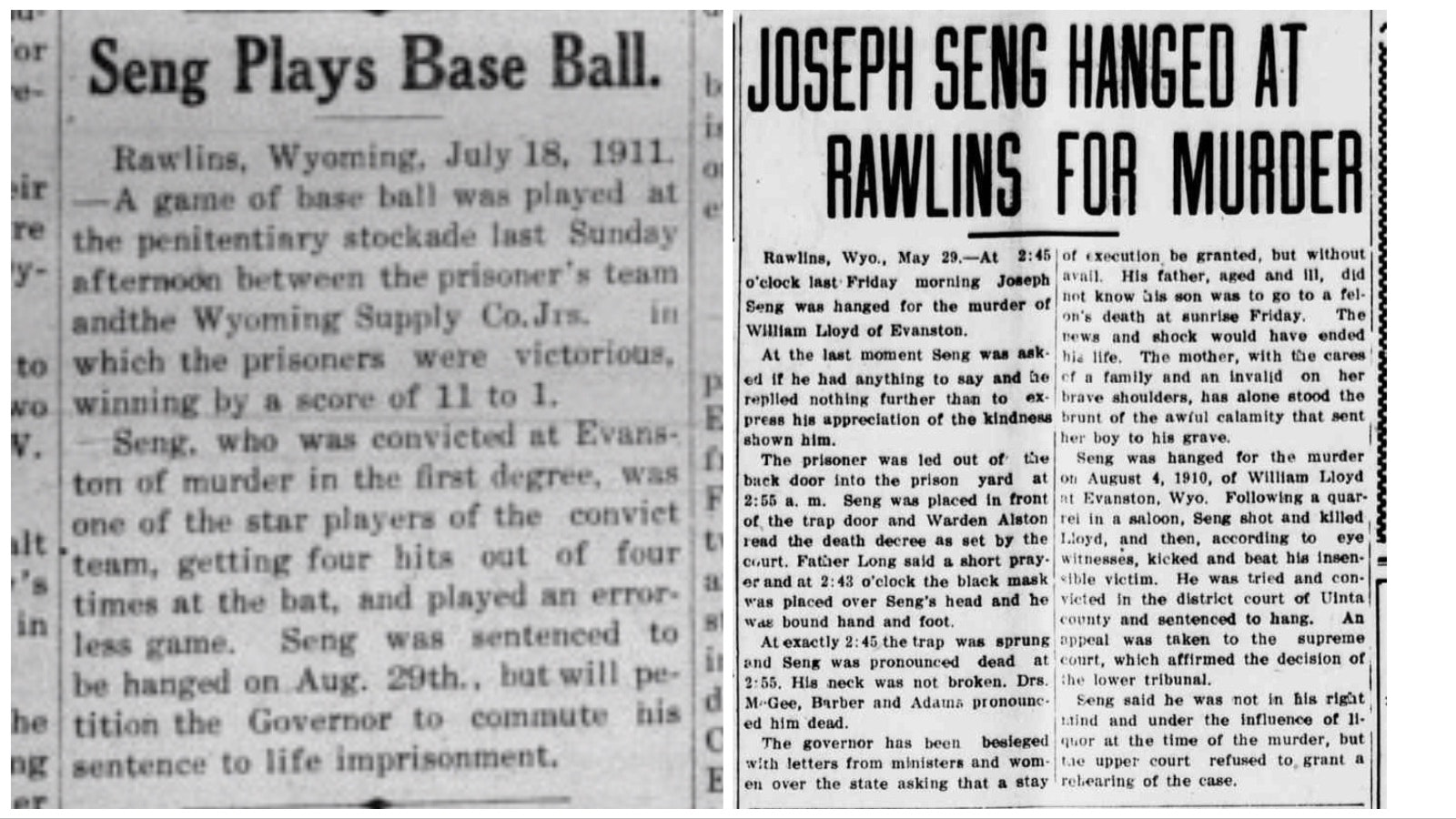

Carbon County Journal made the following observation of the game in its July 21, 1911 issue:

“Warden Alston has got a fast team as our Juniors are classed as one of the best amateur teams in the state and it takes a good team to defeat them, although they were on grounds that were new to them and also that they played one of the oddest games ever played in the state caused them to be a little nervous.”

Prisoners made a barrel of lemonade that was passed out on the sweltering afternoon.

The game was noted by newspapers across the country, including The Washington Post, which ran the headline in its sports section: “Slayer Scores Home Runs: A man under death sentence helps convicts win first game.”

It was Seng the media was interested in. His backstory read like a dime-store novel. A pretty boy “Babe Ruthless” who, rumor had it, killed his lover’s husband in a jealous fit of rage.

Struck Out Swinging

Leaving a large family back in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Seng headed west in 1908 as a 26-year-old looking for a fresh start. He found it with the Union Pacific Railroad in Evanston, Wyoming, where he was hired on as a night watchman.

William Lloyd was Seng’s immediate supervisor and a detective for the railroad.

In her 2014 book “The Death Row All Stars: A Story of Baseball, Corruption and Murder,” Chris Enss contends Seng had an affair with Lloyd’s wife, Alta. While it makes for a juicy subplot, this speculation can be corroborated nowhere.

Enss also authors other erroneous information concerning Alta’s death and burial place. Enss’ 2004 book on the subject, “Playing For Time: The Death Row All Stars,” is so error-filled as to practically be a work of fiction.

Alta, in fact, remarried Edward H. Smith in Green River on Nov. 20, 1911. The couple moved briefly to Twins Falls, Idaho, before settling in Bayard, Nebraska. Alta Smith died in August 1975 at the age of 89.

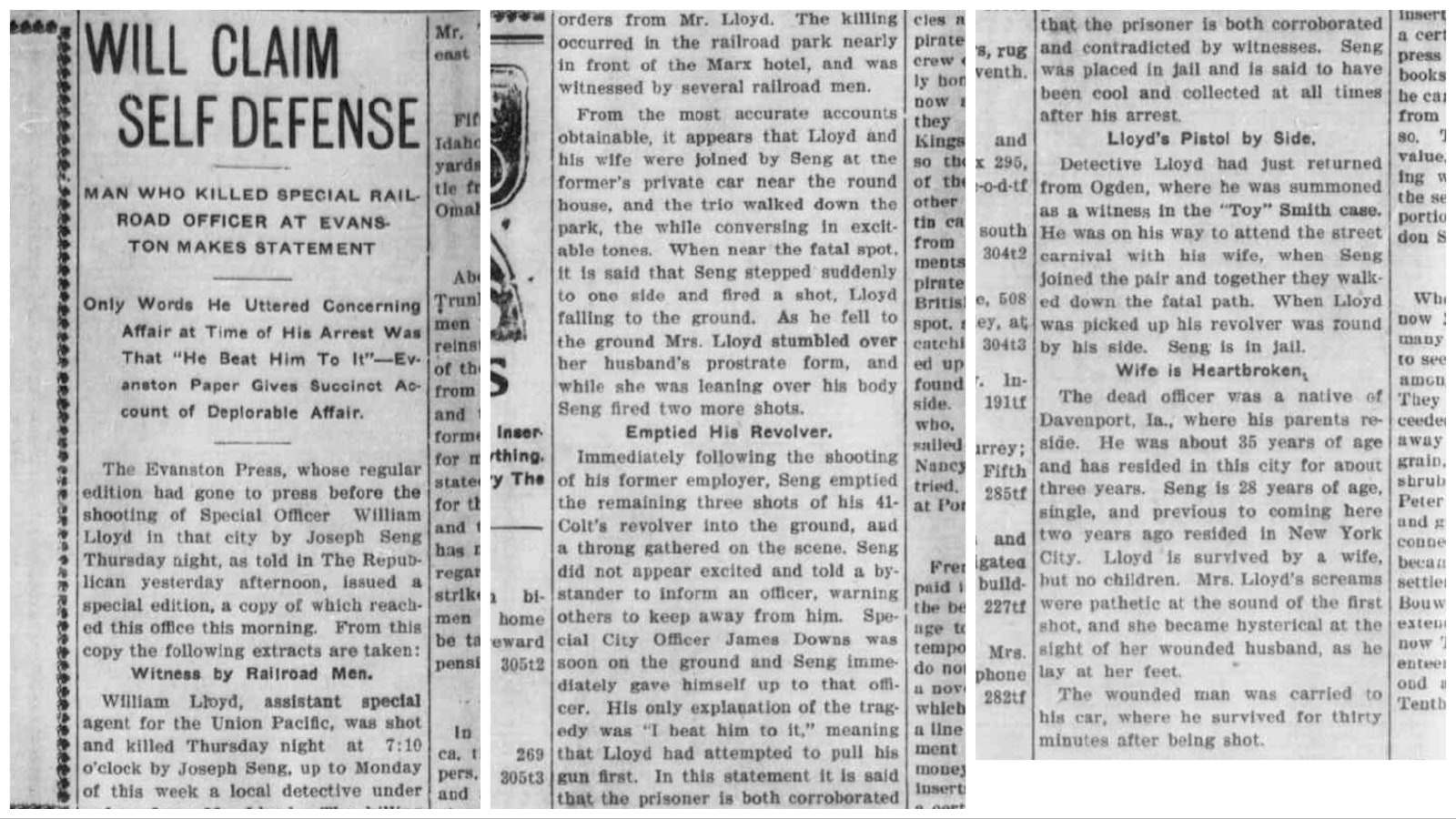

One thing remains certain: William Lloyd and his wife were walking down the street in the vicinity of the Marx Hotel in downtown Evanston on Aug. 4, 1910, when Seng confronted the couple.

Witnesses would later testify they heard Seng saying earlier in a bar that he was out to get Lloyd. The issue may have been over Seng’s termination days prior to the incident.

At around 7:20 that night, the altercation became deadly serious. Both men were armed, but it was Seng’s Colt .41-caliber that blazed first. He put two bullets into Lloyd’s head and emptied his revolver into the ground next to the fallen victim after that.

Alta reportedly wept uncontrollably over her husband’s body. Lloyd clung to life for a half hour, but eventually succumbed. Seng was reportedly calm after the shooting. He asked bystanders to get a lawman so he could surrender himself.

According to the Laramie Republican, “Special city officer James Downs was soon on the grounds and Joseph immediately gave himself up to that officer. His only explanation of the tragedy was, ‘I beat him to it,’ meaning that Lloyd had attempted to pull his gun first.”

The Republican paper called it a “deplorable affair,” but the crime may not have been as cut and dried as originally reported. Eyewitnesses both corroborated and contradicted Seng’s version.

Suicide Squeeze

Whether because of his compelling backstory or his prowess on the field, Seng was the one newspapers focused on when the convicts played. The attention showered on Seng and the rest of the players did not sit well with their cellmates. Trouble was brewing.

An attempt was made on Seng’s life. A disgruntled inmate pushed a heavy box of sand off a walkway above Seng, narrowly missing him. Threats against the players were a constant thing while in confinement.

Turmoil inside the prison walls leaked out into the community. Rumors of the penitentiary baseball team getting preferential treatment, even the potential commuting of Seng’s sentence, were linked by some newspapers to the governor’s possible involvement.

Meanwhile, the WSP All-Stars practiced hard throughout July for its second game. Sagan barked at his players whenever they made an error in the field, telling them if they played poorly there would be consequences, even time added on their sentences.

Aug. 5, the All-Stars took the field for the second time. It was another game with the Rawlins Juniors and another 11-1 blowout win for the prisoners. Once again, the 5-foot-5 Seng led the way with four hits in four times at bat.

The Laramie Daily Boomerang featured a “Seng Plays Baseball” story tucked in neatly between a feature on Cleveland Naps manager George Stovall and a recount of Laramie’s 9-1 win over Greeley.

Seventh Inning Stretch

Unrest at the state pen continued that August.

Warden Alston assured the public he had quashed an attempted assassination on his own life. He also recovered two escaped prisoners who walked off a work detail Aug. 9. Then, on Aug. 15, a guard was shot and killed in an escape attempt.

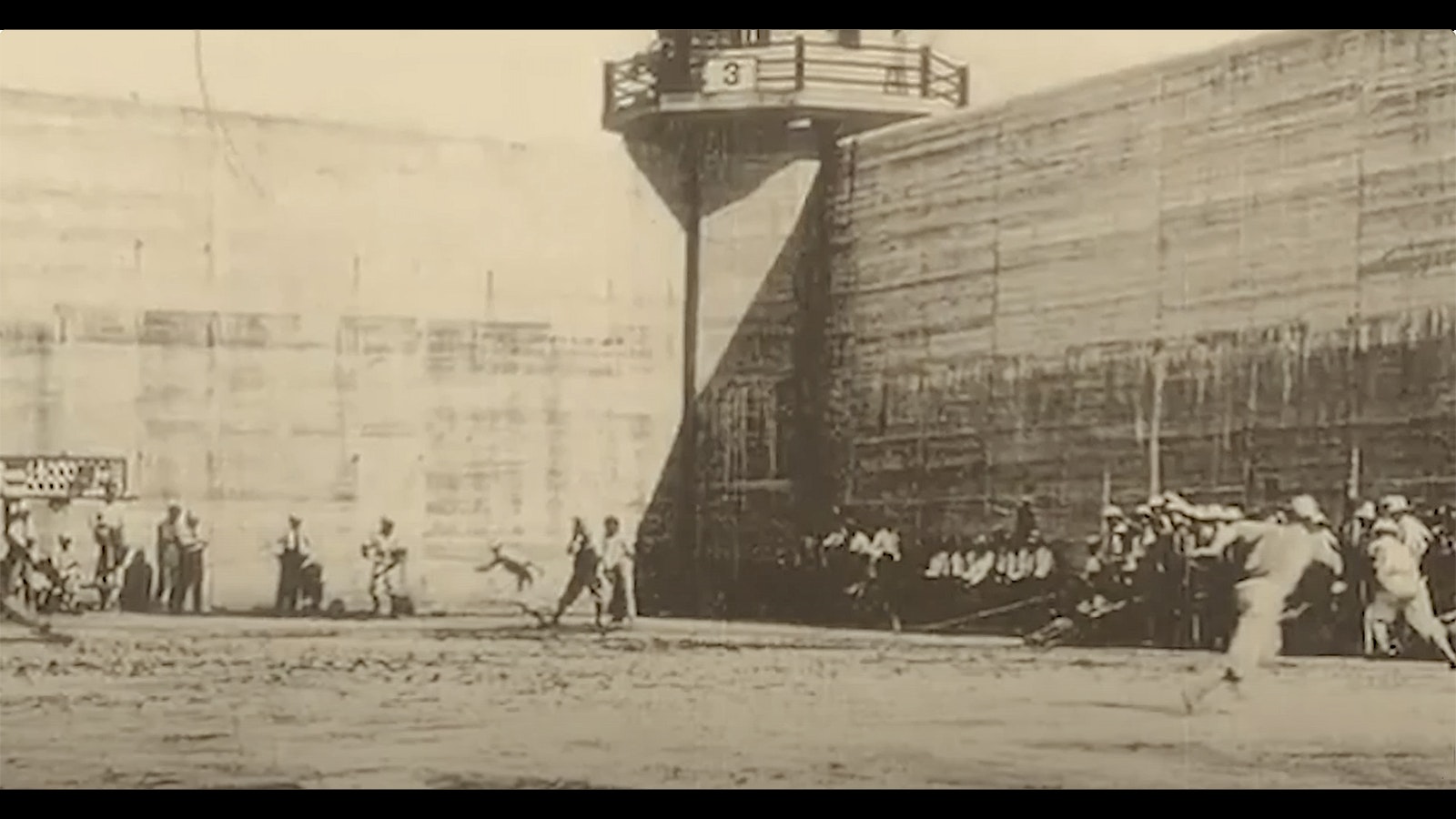

Despite internal issues and some pushback regarding the wisdom of allowing the baseball program to continue, Warden Alston announced his team would play its first game outside prison walls later in August.

The Carbon County Journal reported Alston as assuring there was a “general demand to see his fast team of convict ball players play.” The warden asked only that fans refrain from mingling on the field with the inmates and remain in the stands at the fairgrounds.

Meanwhile, the third of a four-game set was scheduled for Aug. 13. The Rawlins Juniors were out for revenge after being showed up twice and outscored by a combined 22-2 in the pair of losses.

But Cameron was again nearly unhittable for the WSP All-Stars, allowing just six hits and surrendering four runs while fanning 14. Seng went 2-5 with two runs scored in the 11-4 victory for the cons.

“Prisoners Win Again,” the Rawlins Republican headline read as the game was recapped alongside box scores from Rawlins’ games against Junction City (Kansas) and Salt Lake City.

Extra Innings

With Seng’s execution scheduled for Aug. 22, Governor Carey was petitioned to commute his sentence from death to life imprisonment. Letters from Seng’s mother, his spiritual advisor back home (the Rev. Peter Masson) and the prison’s doctor (Dr. Griffith Maghee) were received by the governor, who promised he would look into the matter. After all, Carey had recommended the pardon of 15 other prisoners just that year.

Seng continued to work hard in baseball practice and became a model prisoner. When the date approached for the All-Stars’ final game of the season, Seng had hopes that his sentence might indeed be commuted. After all, his supposed execution date of Aug. 22 had come and gone and here he was about to play in another baseball game days later.

Overland Park was the site of the fourth and final game between the WSP All-Stars and the Rawlins Juniors on Aug. 27. It would be the first time the cons would play in public. Security was tight.

Under heavy guard, the All-Stars were led onto the field in front of a packed house. No excuses this time for the Juniors. They could not claim nervousness at the thought of playing on prison grounds at the stockade. This game was to be played on their home field.

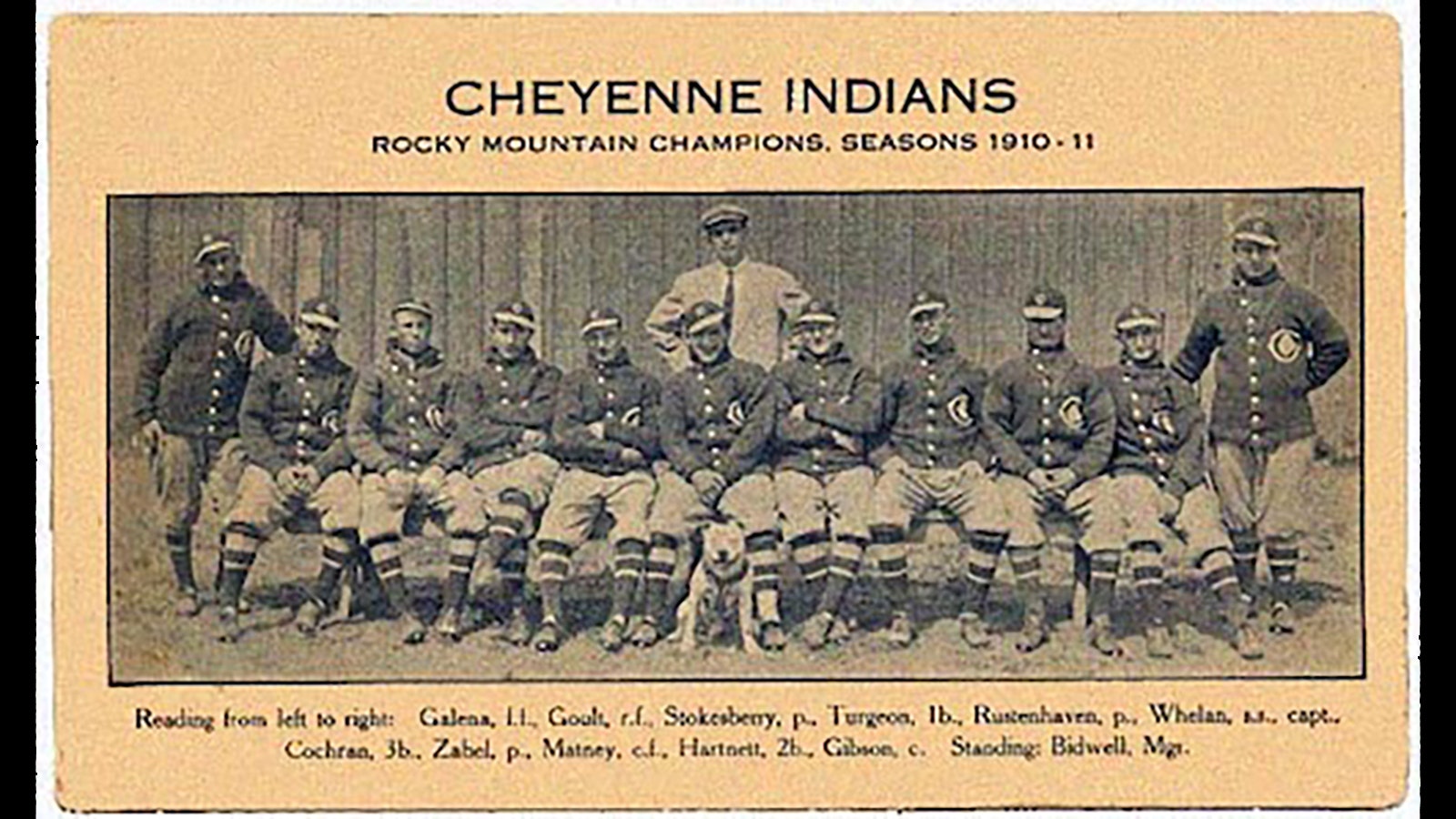

Earlier in the week, Rawlins split a doubleheader with the “invincible” Cheyenne Indians. The semi-pro Indians team went 70-25-5 on their way to a second consecutive Rocky Mountain League championship in 1911.

Incidentally, three players from that famed Indians team would go on to professional careers in the majors. Pitcher Claude Hendrix signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates and southpaw Harry Rustenhaven pitched for the New York Giants. Third baseman George Cochran was a member of the Boston Red Sox world series winning team in 1918.

Undaunted, the WSP All-Stars again bested the Rawlins Juniors 15-10. There are no newspaper accounts of the game that detail the box score or any stats.

After the win, the convicts returned to the state prison, surrendered their equipment and returned to their cells. They would never play again.

Bottom Of The 9th

Governor Carey penned a letter to Warden Alston in September expressing his concerns about the prison baseball team. The governor was worried about the potential impression of wrongdoing concerning the play-to-pay scheme of shortening sentences, as well as rumors that gambling was also taking place on the games.

Warden Alston gathered the team later than month and told them it was over. The short-lived experiment was discontinued in favor of a penitentiary-wide education program.

The season ended, the team dissolved, Seng anxiously awaited word on his final stay and appeal. It was denied. In early April, he learned his new date with the hangman was to be May 24, 1912.

Right up until the day of his execution, Seng held out hope that the governor might commute his sentence to life in prison. Dozens of letters were penned on his behalf. During his tenure as governor, Carey pardoned 63 people and commuted the sentences of 96.

But it was not to be for Seng.

The same gallows used to hang famed Wyoming bounty hunter Tom Horn at the Laramie County jail eight years prior was dismantled and brought to the Wyoming State Penitentiary. The Julian Gallows, as it was known, was named for its inventor James P. Julian. It operated by the use of a water pail which, when drained sufficiently, sprung a trap door, thus circumventing the need for an actual hangman.

At 2:45 a.m. on his scheduled execution day, Seng was fitted with a black hood. He stepped on the trap door, pulling the cork on the water bucket. Not a minute later, Seng “fell five feet and was jerked into eternity at the end of a rope,” according to the Carbon County Journal. His neck was not broken. He slowly strangled. Seng was pronounced dead at 2:54 a.m. by three attending doctors.

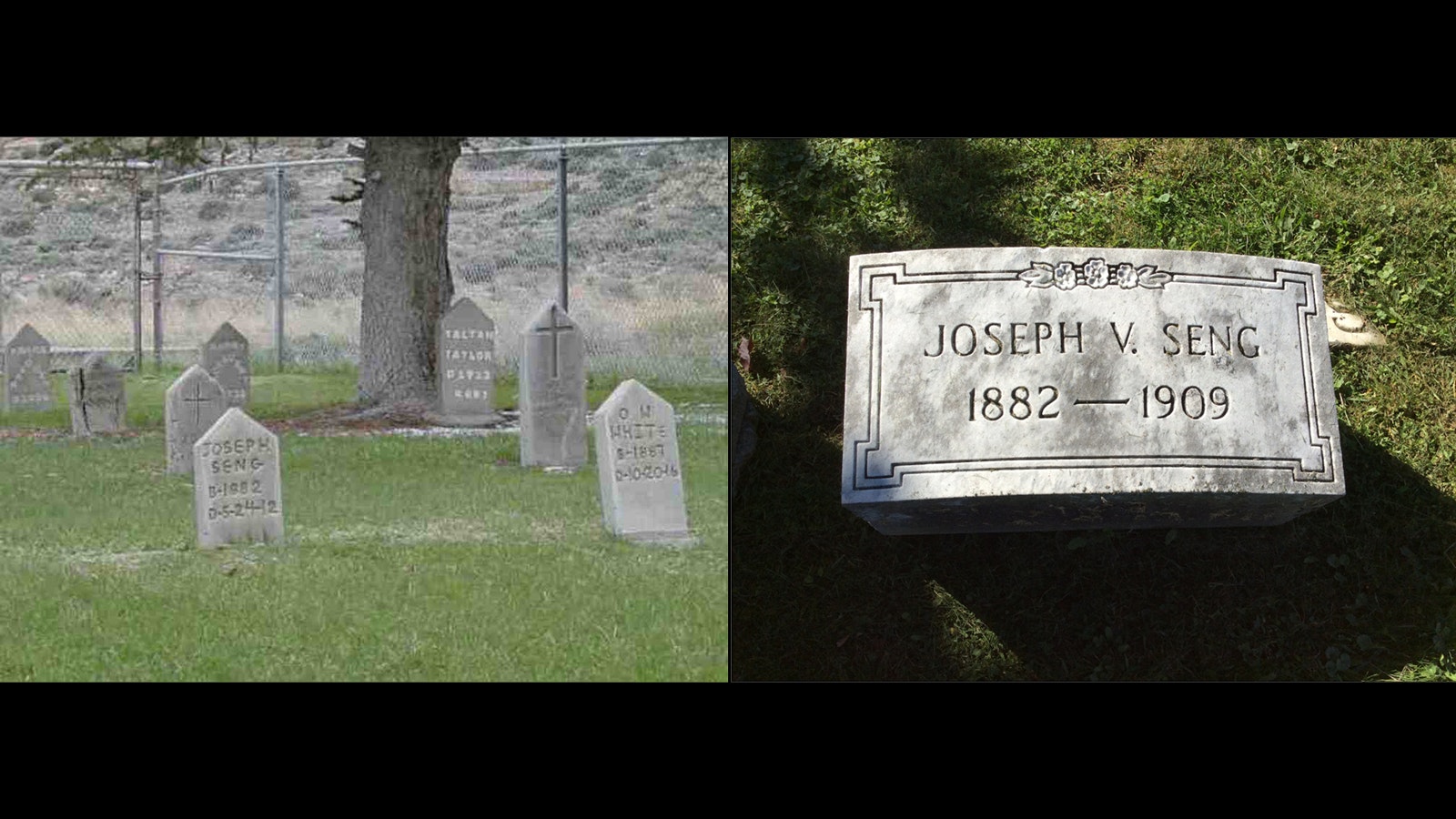

Seng’s body was turned over to county undertaker H. Rasmussen. The Journal reported Rasmussen promised to ship Seng’s body back to Pennsylvania for burial in his hometown, but that may not have happened.

A headstone can be found at the old “Frontier Prison” in Rawlins bearing Seng’s details. Another burial site in Allentown’s Sacred Heart of Jesus Catholic Cemetery also displays Seng’s name on a headstone, but the date of death is incorrect.

Seng was the first person hanged at Wyoming State Penitentiary. Eight more would follow until the gallows were replaced by the gas chamber in 1936. In all, 14 men were executed at the state pen. Another 250 died of natural causes, suicide, or were victims of inmate violence until the lockup closed down in 1981.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.