She was the largest wooden ship ever built, and her name was Wyoming.

Naming a massive wooden ship after a landlocked state might seem a bad omen, but the history of the Wyoming is one of industry, investment, the end of an era and a ship connecting a fledgling Western state to the world. The Wyoming was the biggest of them all.

And while the Wyoming may be no more, she’s far from forgotten.

Western Money In Eastern Docks

The story of the Wyoming begins at the Percy and Small Shipyard along the banks of the Kennebec River in Bath, Maine.

Samuel Percy and Frank Small opened the shipyard in 1894 to build massive wooden cargo ships, and theirs became the largest wooden schooners ever built.

To finance their endeavors, they specifically sought investments from wealthy businessmen in Western states. Enter Bryant Butler Brooks, Wyoming’s governor from 1905-1911. His brother John Brooks invited Percy and Small to visit the governor in Wyoming and facilitated the first investment from a Wyoming businessman.

“They agreed the best way to get over this Western indifference to the shipping trade is to get them involved in building ships,” said Con Trumbull, president of the Fort Caspar Museum Association.

Governor Brooks’ money helped build a five-masted schooner named the Governor Brooks in his honor. He traveled to Maine for her launch in 1907. While there, he met and had lunch with Maine’s governor, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlin, who famously defended Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg.

The Governor Brooks was an immense success for Percy and Small and their investors, so they returned to Wyoming to find $175,000 (roughly $5 million today) to build an even larger schooner. That money came from the private business earnings of Wyoming’s politicians, which is how the ship got her name.

“All of the old politicians were businessmen, and they all had their own businesses,” Trumbull said. “Governor Brooks was involved in ranching, banking, lumber, mining and oil fields. These were all big investments from private individuals. Using Wyoming capital, they built the largest wooden sailing vessel ever built.”

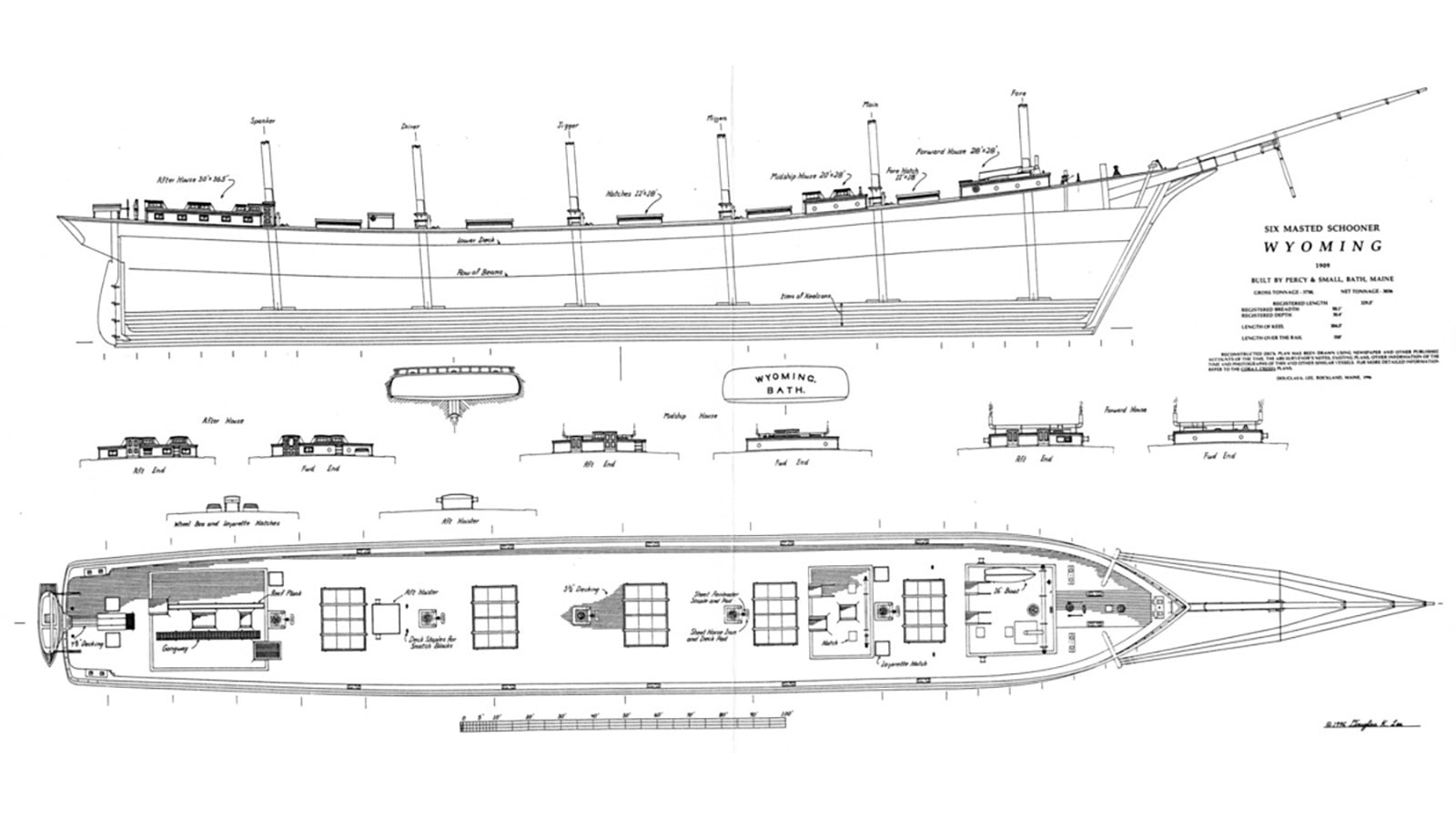

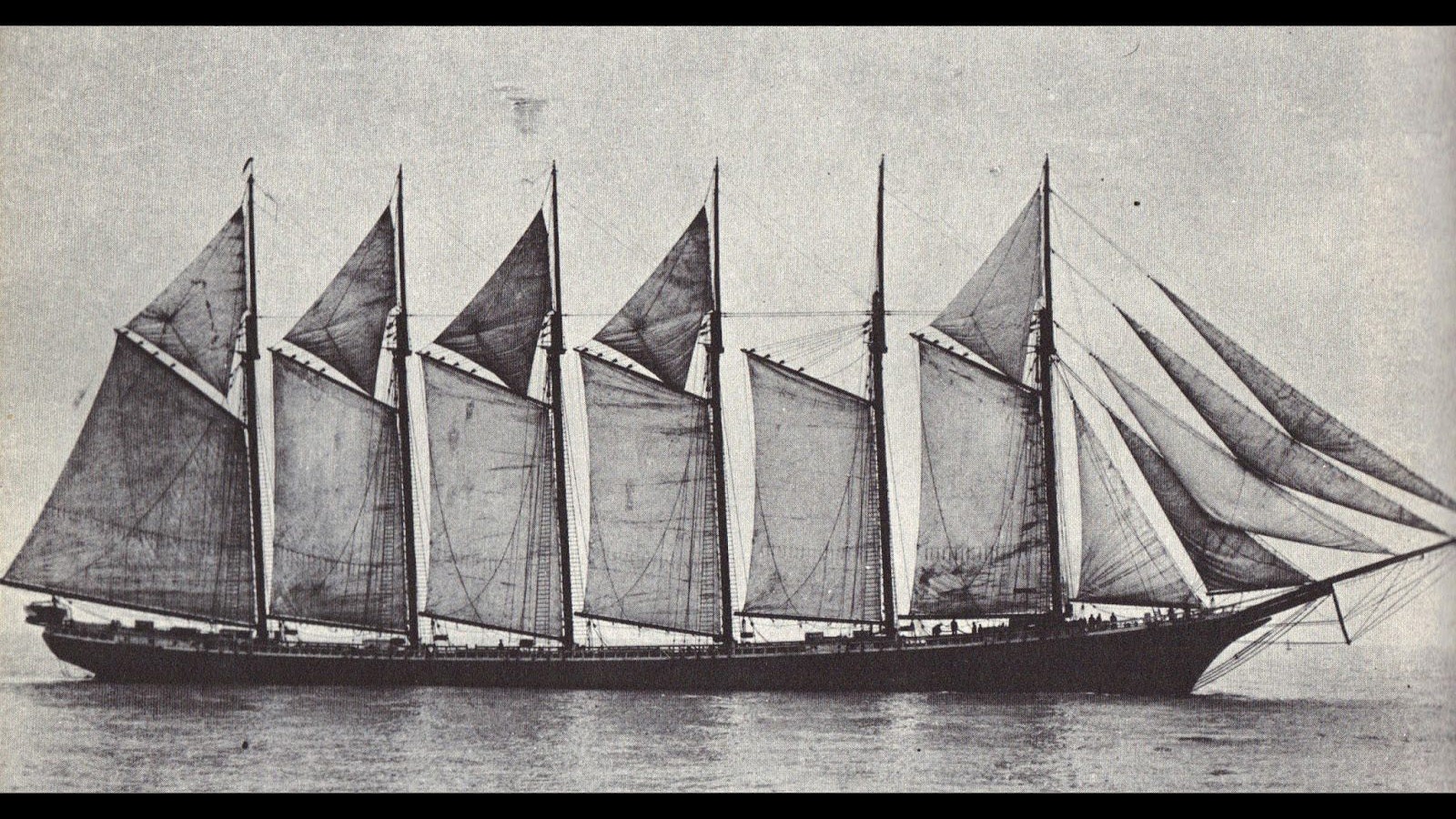

When she was finished, the Wyoming measured a massive 450 feet long with six 126-foot-tall masts. The 22 sails on those masts flew 12,000 yards of material. It took 1.5 million feet of Southern pine and Chesapeake Bay white oak to build, and when finished weighed in at about 3,800 tons. Even the ship’s anchors were massive, weighing 8,500 pounds each.

And for its time, the Wyoming had some modern conveniences, with running water in the bathrooms and a telephone communications system throughout the ship.

Lena Brooks, daughter of the governor, christened the Wyoming at its launch Dec. 15, 1909, and the ship departed on her maiden voyage the following week. One of the flags that flew atop her masts throughout the ship’s active service career was the V-V cattle brand of the Brooks Ranch.

How Big Can It Get?

The Wyoming was as much an experiment as a lucrative business venture. At the time, nobody knew how big a wooden ship could be before its size became untenable, but Percy and Small kept pushing the envelope with each ship.

Trumbull said the Wyoming was never intended to be the world’s largest wooden ship, and none of the Cowboy State investors expected it to keep that title.

“The Wyoming ends up being the largest not because of any plans. That was the limit of the technology,” Trumbull said. “The ships got too big, and it was hitting the limits of the technology for sailing ships.”

Appropriately enough, the Wyoming was designed as a coal-carrying schooner. At full capacity, she could carry more than 6,000 tons of coal, doing the work of several smaller schooners. This made the ship very profitable.

But that capacity and profitability came at a cost. The ship sagged when fully loaded with cargo and hogged when empty.

The constant downward and upward bending was problematic. Percy and Small built metal cross-bracing on her hull, which mitigated rather than solved the problem. In heavy seas, the wood twisted and buckled, allowing water to end the hold.

The Wyoming has roughly the same dimensions as Noah’s Ark (which the Bible says was 440 feet long) but it was also a testament to the limits of building ships that size out of wood.

Simply put, that’s because “wood bends,” Trumbull said.

Successful Stateside

Despite the sags and hogs, the Wyoming had an immensely successful and uneventful career transporting coal and other cargo along the East Coast of the United States and beyond. Governor Brooks made back his investment and much more in dividends.

Trumbull said the ship had “an illustrious career,” making a successful trip to Europe in 1916 and completing a voyage to South America, in addition to numerous trips up and down the East Coast. And the state of Wyoming benefitted from the success of the ship.

“It helped bridge the gap,” he said. “It brought about the social and economic partnership between Wyoming and Maine that was very successful.”

When Percy and Small sold the Wyoming in 1917 for $400,000, it was a windfall for them and Brooks. The France and Canada Steam Ship Co. bought it and made back the entire purchase cost within six months of service.

Snapped In Half And Sunk

The Wyoming’s career came to a tragic end March 11, 1924. After departing Norfolk, Virginia, with 5,000 tons of coal bound for Canada, the ship encountered a nor'easter, a hurricane-like storm off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

In the intense storm and heavy seas, the Wyoming continuously sagged and hogged until she finally buckled, snapped in the middle and sank. All 14 crew members aboard were lost.

Trumbull said Brooks had just landed in New York City after a trip through Europe when he saw a headline that the ship he helped build had sunk. But back in the state of Wyoming, the loss barely registered.

By 1924, metal steamships had made the massive wooden schooners built by Percy and Small obsolete. In fact, they had closed their shipyard in 1920, four years before the Wyoming foundered and sank.

“By the time the ship sinks, sailing ships are out of the public consciousness,” Trumbull said. “It wasn’t news in Wyoming. It’s like airplanes. When the latest and greatest planes take over, that’s the new news, and the old planes fade from history.”

The Wyoming’s wreck was rediscovered by American Underwater Search and Survey Ltd. in 2003. It was in 70 feet of water off the coast of Cape Cod. An analysis of the wreck indicated she may have hit the ocean floor in the storm, which caused the ship’s back to buckle and break.

Wyoming And The World

The Wyoming was the last ship of its kind, built at the end of an era of wooden shipbuilding. However, its success and impact on the history of Wyoming is undeniable.

While the wreck of the Wyoming remains under the waves off the coast of Cape Cod, a massive sculpture of the ship stands at the site of the Percy and Small Shipyard in Bath, now the site of the Maine Maritime Museum. The sculpture was built to the exact dimensions of the ship.

“You see it from a distance,” Trumbull said. “You see the tops of the masts. You see the burgee with the name of Wyoming flying high over the shipping city. And you can stand there and think back to what it was.”

Trumbull would be the first to admit he has a personal stake in the ship’s legacy. Lena Brooks, the daughter of Governor Brooks who christened the ship at its launch, is his great-grandmother. When the Maine Maritime Museum finished the sculpture, Trumbull’s mother was invited to attend the opening and christen it.

A common refrain among Wyoming politicians is that the state is a small town with really long streets. The legacy of the Wyoming, in Trumbull’s view, is that those long streets were extended beyond the state’s landlocked borders to benefit a nation and the world.

“We are a very small state,” he said. “We can feel disconnected from the world. The Wyoming shows that even over 100 years ago, the people of Wyoming could get connected to the bigger picture of the nation’s development and become part of that story.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.