Native American culture is intertwined with the buffalo. The social, physical and spiritual connection between the tribes of the Great Plains and the massive herds of shaggy beasts is central to a new documentary by renowned filmmaker Ken Burns.

The tribes used every part of the animal, head to tail. They even used the excrement as fuel for their fires. They mimicked the buffalo’s vocalizations in their ceremonies, wrapped their newborn babies in buffalo robes and swathed their elders in the same robes when they died.

Every tribe held ceremonies related to the buffalo. They believed the animals had their own societies and customs and were capable of changing forms to communicate directly with humans.

“You don’t just go out and kill a buffalo – you go to the ceremonies, you pray and you ask for the gift of a buffalo. You ask that a buffalo will give itself to you,” said Marcia Pablo, a member of the Pend d’ Oreille-Kootenai Tribe. “It’s a spiritual relationship, you do everything with a pure heart.”

The tribes of the Great Plains developed a complex relationship with buffalo over a 10,000-year period and never viewed themselves as superior to the animals on the land.

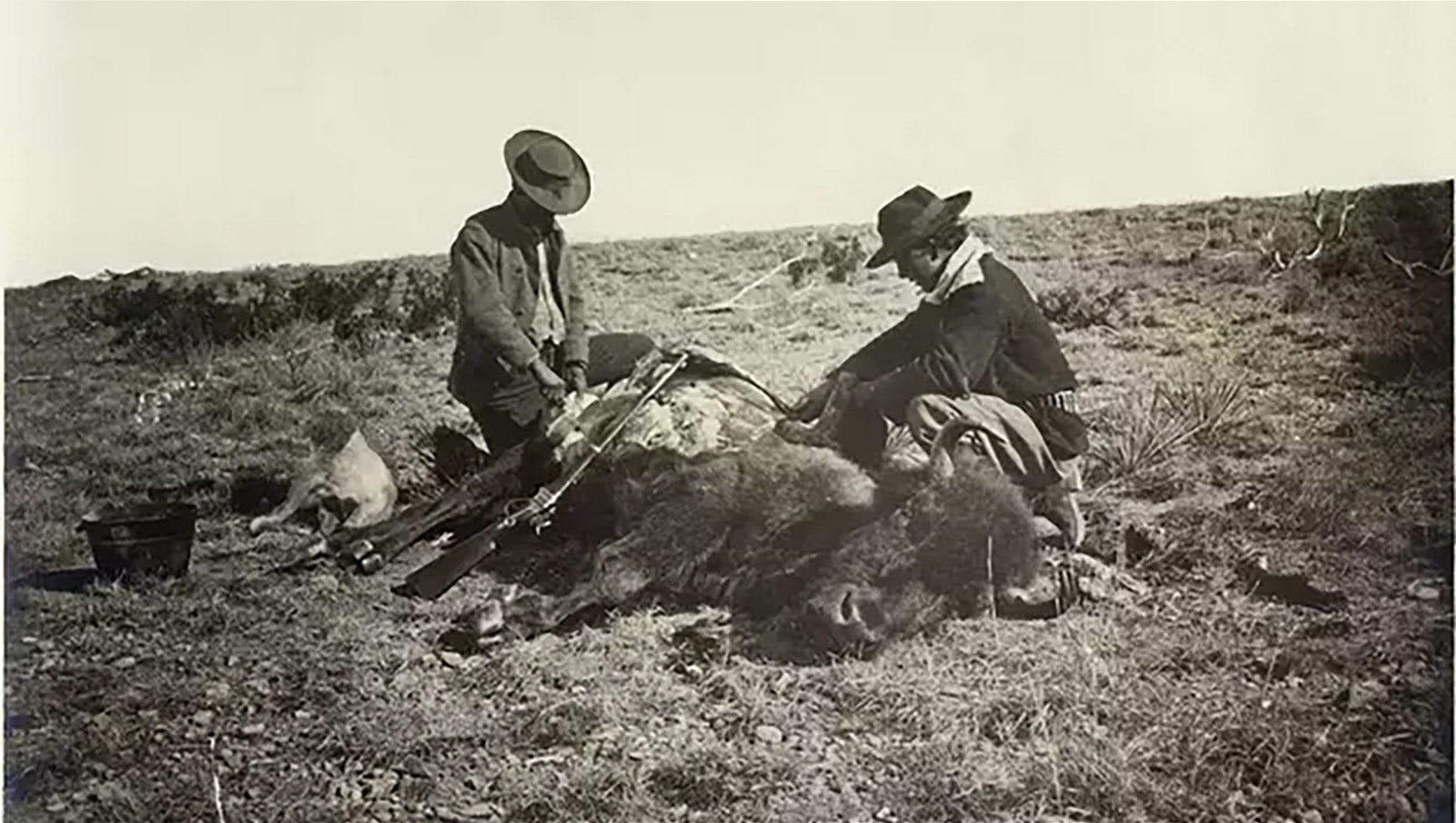

The fact that white men drove the bison to the brink of extinction in close to one decade sheds light on the distinct differences related to how people view the natural world.

This divergence of thought is at the center of Burns’ new documentary, “American Buffalo.” It’s a two-part series, about four hours total, set for release on PBS on Oct. 16.

A Long Time Coming

Burns and his writing partner Dayton Duncan have pretty much nailed the art of narrative story telling. Their documentaries “The West,” “The Dust Bowl,” “The National Parks” and “Lewis and Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery” have all been intertwined with America’s most iconic mammal.

In an interview with Cowboy State Daily, Duncan said they’ve been kicking around the idea of a “bison biography, if you will,” for the past 30 years.

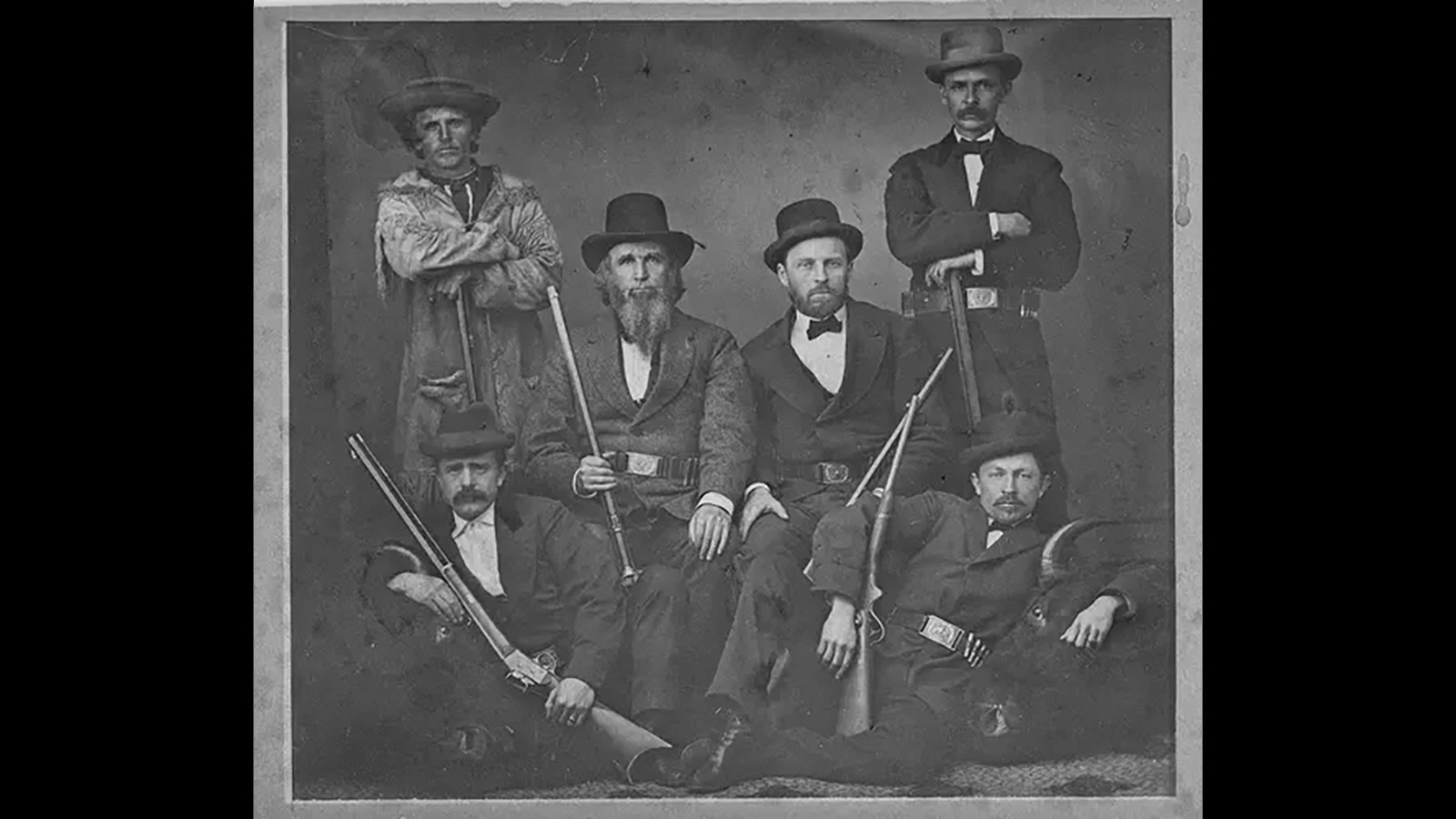

In the 1996 documentary “The West,” they told the story of the profits that motivated hide hunters in the 1870s and how in one month a hunter sold 300 hides and made $1,000, the equivalent of an average man’s wages for an entire year at the time.

In the Lewis and Clark documentary, they told the story of the members of the Corps of Discovery throwing sticks to encourage massive herds of bison to move out of the way and of beaching their canoes on the Yellowstone River for several hours to allow a herd to pass.

In the documentary “The National Parks,” they describe how Yellowstone became the refuge for the last free-roaming herd of buffalo in the 1890s and how poachers motivated by lucrative profit and limited consequences continued to threaten the animals.

“It’s a very American story of different people in different places leading the nation in a different direction,” Duncan said. “It’s a historically important story, a cautionary tale of morality. As capable as we are of destroying the natural world, it shows we can change direction and lead thinking in a more hopeful direction, which is important for us to consider today.”

Tried And True Formula

Documentary fans will recognize the familiarities of the Burns team’s formula. The authoritative voice of Peter Coyote as narrator, the commitment to research and delivery of the important details that weave the story together and interviews with numerous sources close to the topic.

In one interview, Steven Rinella, a hunter and founder of the Meateater franchise, describes bison as extreme athletes.

“If you see one out grazing it looks so slow,” Rinella said. “It looks like a parked car sitting out there. But they can clear a 6-foot fence and can jump 7 feet horizontally. They can hit a speed of 35 mph, and you’re talking about an animal that weighs 1,800 pounds. They’re like a souped-up hotrod of an animal hiding in a minivan shell.”

Wyoming And Bison

The film is full of Wyoming mentions. Yellowstone National Park, where the effort to save the last free-ranging bison in the U.S. originated, is an obvious connection.

Chief Washakie, leader of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe and Wyoming’s most prominent native leader, is quoted in the film. Written quotations from the chief include his account of cattle and sheep being driven into Wyoming and how destructive that movement was to the riparian areas along the Platte River.

When Washakie said that westward settlement was causing his people to starve, the comment was related to the slaughter of the buffalo, Duncan said.

Buffalo Bill – The First Great Plains Roadside Hustler

In 1889, Buffalo Bill Cody was the most famous American in the world.

He was the central figure in his own Wild West Show, featuring a small herd of about 20 stampeding buffalo to close every performance. The outdoor show promised a Wild West experience inside of three hours.

Cody’s exploits were featured and greatly exaggerated in many dime novels of the time. Some of those tall tales were incorporated into the Wild West Show.

A stagecoach was attacked and saved by Buffalo Bill. A wagon train was raided and saved by Buffalo Bill. A settler’s cabin was surrounded by Indians and saved by Buffalo Bill.

A reenactment of the Battle of the Little Bighorn ended with Buffalo Bill showing up while the words “too late” were displayed to the audience.

The writer Dan O’Brien said crowds of people loved the buffalo in Cody’s Wild West Show and that Cody became “the first Great Plains roadside hustler.”

In 1886, 1 million people attended Cody’s Wild West Show on New York’s Staten Island and another million attended the show the following winter in New York’s Madison Square Garden.

In 1887, the show toured Europe, performing in England at Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee. Eighteen buffalo made the journey across the Atlantic.

Episode 2

The second half of the documentary delves into the lives of the people who saved the buffalo from extinction, some of them unknowingly.

Many of these early conservationists, including one who would become president – Theodore Roosevelt – agreed that for westward expansion to continue and for America to reach its “Manifest Destiny,” the buffalo had to go.

“Episode 2 tells the story of a motley collection of Americans who in one place or another and for different motivations, managed to rescue some buffalo and started small private herds,” Duncan said. “It resulted in a national movement to save the species from extinction.”

Removing the buffalo is what drove the Great Plains tribes out of their territories and onto reservations.

From 1870 to 1890, new industrial processes added value to the buffalo trade. A new tanning process was developed that turned buffalo hides into the belts that drove the machines that powered factories, and in turn increased demand for more hides.

Duncan said that at one time, buffalo were in every state. Historians are uncertain how many there were at their peak, but they believe there were as many as 30 million in the early 1800s.

The film tells the story of Texas rancher Charlie Goodnight and how although he didn’t want buffalo on his land because they competed with his cattle for grass, he saved a few and started a herd at the request of his wife. That herd later became a key part in saving the species.

It further tells the story of the Comanche Chief Quannah Parker and how he witnessed the extermination of the buffalo on the southern plains, and later wept when a small herd was loaded onto rail cars and shipped west from New York to Oklahoma and released.

In addition, it tells the story of how George Bird Grinnell and Theodore Roosevelt created the Boone and Crocket Club, a hunters organization that played a key role in the bison conservation effort.

“We hope this story helps people understand and feel the devastation that native people felt when the buffalo were brought to the brink of extermination,” Duncan said. “It’s a portal into a larger American story that touches on what our relationship should be with the natural world as humans and a nation.”

Duncan wrote a companion book to the film titled “Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo.” The book’s release date is set for Oct. 10.