One of the last things people passing through the remote Lost Cabin area might expect is to see is an architectural wonder sitting in what is the high plains desert. It’s a big mansion built of sandstone and pinewood, with a turret at the top that makes it seem like a castle.

It is the multi-story mansion of J.B. Okie, Wyoming’s “sheep king,” a man who came out West with nothing more than the clothes on his back and some spare change borrowed from his mom for a train ticket to Rawlins.

Okie dreamed of making his fortune as a cowboy, but became a sheepherder instead — and made millions of dollars doing it.

It wasn’t an easy road, but the incredible success is evident with just a glance at the five-bedroom mansion.

It includes a third-story cupola out of which Okie would gaze at the land around, most of which he owned, as well as an additional servants’ quarters over the garage space and a tremendous sandstone wraparound sunporch.

Today the mansion is still there, about an hour northeast of Riverton and is not readily visible to the casual traveler until one gets really close up. Ancient cottonwood trees have surrounded the place.

In fact, well before the mansion comes into view, there are several signs that warn of “bad gas” when lights are flashing.

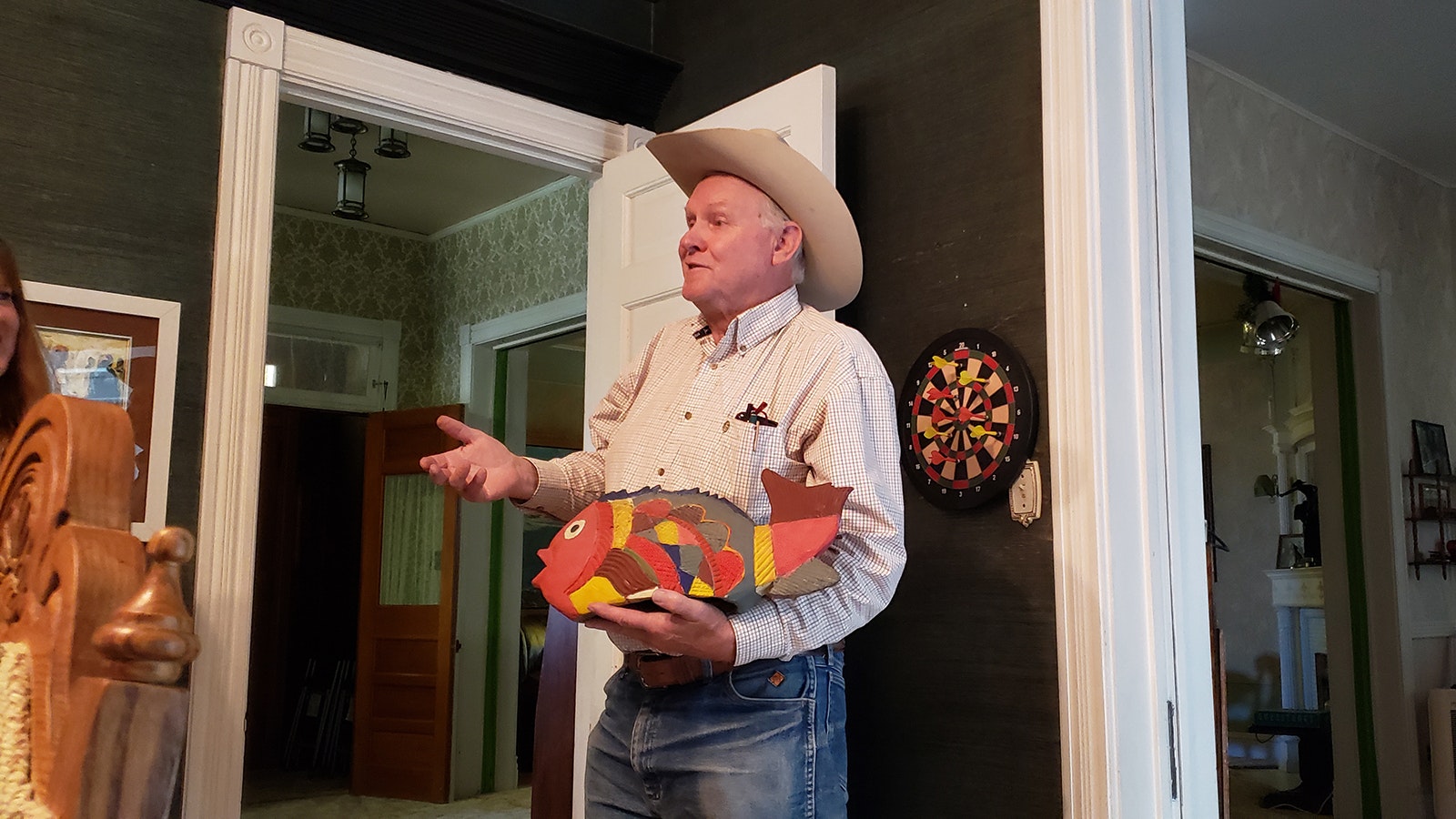

That “bad gas” is hydrogen sulfide from nearby oil and gas activity. It’s one of the first things the home’s present occupant, Zane Fross, tells guests about before he gives a tour of the 122-year-old place.

“We are surrounded by pipelines to carry the nasty gas from 26,000 feet below the surface,” Fross told a recent tour group. “They say your first breath (of that gas) is your last breath. So, I want you to be aware you’re here at your own risk the whole time. I’ll do my best to keep you safe.”

A Glass Wonderland On The Plains

One of the favorite stories Fross likes to tell is about the glassed-in aviary that Okie added to his mansion after marrying his second wife.

“It was large enough to be a house,” Fross said. “And he boasted of having the largest collection of exotic birds in the territory.”

The aviary was built in 1910, after Okie and his second wife Clarice went on a six-month world tour to places like China, Paris, and Japan.

When they returned to Lost Cabin, they had bought a home in Denver and another in Pasadena. They also built California-style bungalows, and the giant glass birdhouse.

It was a glass wonderland with more than 140 exotic birds, including cockatoos, macaws, and birds of paradise, and the exotic plant life to match, in what resembled a lush jungle oasis.

It must have been quite a contrast to the brown sandy dirt and dried grass that’s more usual for this area.

It’s possible the aviary was just the beginning of Okie’s dreams for the place with his second wife.

Years ago, Fross found a set of blueprints while he was working for the Spratt family as a ranch hand, helping them with maintenance of the mansion. They outline a much bigger footprint for Okie’s mansion.

“I kind of hid them,” Fross admits. “I kind of brought them over and I hid them here in the big house. We weren’t living here at the time. I was just a ranch hand, right, and never dreamed I’d ever live here. But so, I stored them in a closet here, out of the sun.”

The Spratts eventually sold the mansion to ConocoPhillips, which in 2009 asked Fross if he wanted to live in the mansion. Fross said he has been working through a process with the oil and gas company since then to eventually own the mansion.

The blueprints Fross found show a massive addition that would have come 80 feet out from the mansion. On one side of that addition, a wing of rooms 20 feet wide. On the other side, a wing 18-foot wide.

Together, the two wings helped define an indoor courtyard with a mosaic fountain.

“The addition was two stories high on both sides,” Fross said. “And the blueprints show that one side would have a master bedroom, which would be Okie’s.”

There were also bedrooms for each of his children in these wings, with their own private bathrooms. An indoor swimming pool was part of the layout as well.

“These are old, old blueprints,” Fross said. “They can’t be copied easily.”

Humbler Beginnings

J.B. Okie didn’t spend his first years in Lost Cabin in anything at all like a mansion, however.

His first home was quite humble — a big trench with a lean-to for shelter. He lived a hardscrabble life of wildcat speculation and almost unimaginable hardship. Not at all the life his well-off parents had planned for their son.

At 16, Okie had been appointed as a cadet in the school of the U.S. Revenue Marine, the forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard. They felt his future would be assured upon successful graduation from the program — and with much less hardship.

But, while on a surveying trip to the West, Okie heard an instructor casually remark, “A man could get rich out here.”

That stirred Okie’s imagination, and, within a year, the 17-year-old had resigned as a cadet and set off to seek his fortune in Wyoming. He rode in on a Union Pacific train with not much more than the clothes on his back.

In fact, after landing in Rawlins, he had only his cadet uniform for attire, which soon earned the would-be cowboy a nickname. “The cadet.” There’s still a draw near Lander still referred to by some as Cadet Draw.

Okie, as it happened, wasn’t great at being a cowboy. He would even later joke he made a “damn poor one.”

Ultimately, he talked his mother into loaning him $4,500 to buy a sheep herd instead.

She had a few conditions. The sheep were to remain hers, and they would divide any profits equally.

Almost Disaster

Okie, as it turned out, wasn’t a great sheepherder either.

He kept his sheep too long in each camp, and he was herding them along the creek when they should have been up in the hills.

There was a terrible snowstorm in 1883, and his sheep were already in such poor condition they couldn’t withstand the record minus 57-degree temperatures. He lost all of his bucks, and his ewes were in no shape for lambing come spring.

He threw his herd in with A.D. Bright’s, another sheep herder, and worked for Bright as a sheepherder for $40 a month. That didn’t even begin to cover his expenses, but Okie gained invaluable sheep sense.

Okie had cash to build back up again at this point. No doubt, he didn’t want to tell his mother he’d lost most of his sheep and needed more money. Instead, he sold off a little shanty he’d built as a youth in Washington D.C., which he’d been renting to a family for $5 a month.

With the $300 from that sale, he bought 150 ewe lambs, increasing his herd from 718 to 868 ewes. Not as many as he’d had before. But as close as he could get.

There would be more winter roller coaster rides in his future, but Okie was more knowledgeable and managed to ride them out, even the particularly bad winter in 1886/87 that ruined so many cattle ranchers. Unlike cattle prices, sheep prices rose thanks to that debacle, making the sheep Okie had left even more valuable.

By 1889, Okie had over 5,000 sheep and the Wyoming Derrick Newspaper took to calling him the “Sheep King.” In the spring of 1891, the Derrick reported that Okie had sheared 12,000-some sheep.

He’d restored his herd and then some. But as Okie’s empire grew, he chafed at the restrictions his mother had on his sheep-herding activities. Facing a downturn in real estate that had dried up her own cash flow, she had forbidden him from making investments in the ranch, to prioritize his payments to her. That was, as he saw it, holding him back from improvements he needed to make.

Okie ultimately bought her out so that he was free to invest where he needed to in his growing empire. A day after, the volatile sheep market exploded on an upward trajectory. That prompted his own mother to sue him, claiming he’d undersold the value of her interest.

A judge, however, determined otherwise, and Okie prevailed in that case — as he would in subsequent suits brought against him, by various others seeking one claim or another on his wealth.

Easy Credit, Easy Street

Freed from his mother’s shackles, Okie opened general stores in not just Lost Cabin but surrounding communities like Lysite, Arminto, Moneta, Shoshoni, and Kaycee. At these stores, he allowed his fellow sheepherders liberal credit, at the low end of market rates, which allowed them to buy what they needed now and pay later, after sheep-shearing or lamb-shipping time.

Hugh Day, a beginning sheep herder, recalled this tale, which he told in the 1970s to a researcher named Karen Love.

Like other ranchers in the area, Day bought on credit at the Bighorn Sheep Company stores and typically paid his bill when he sold his stock. But one morning, when he had ridden to Lysite to get supplies, a clerk told him his credit was no good any more. He’d charged too much, he was told, and would have to pay first.

Just as Day was leaving, however, Okie happened to arrive in his car and asked the man what was wrong.

Hearing that Day had been summarily cut off, Okie went to the clerk’s office and told him, in front of Day and anyone else in the vicinity, that he was to sell Hugh anything he asked for, and that he was to continue to sell to Day until the shelves were empty.

After that, he was to offer Day the shelves, too, if Day wanted them.

In addition to business horse sense, Okie wasn’t afraid to defend what was his, either, Fross said, even against outlaws that struck fear into the hearts of most other people.

When a bandit loaded up supplies with no intention of paying, Okie’s store employees watched from afar, afraid to intervene. Okie stepped into the unsavory character’s path, and fearlessly demanded payment for the items.

The bandit scoffed and said, “Don’t you know who I am? I’m the bad man from the Stinking Water!”

“Well,” Okie replied, pulling his gun out. “I’m the stinking man from Badwater, and you’re going to pay for that.”

Many Firsts

Okie wasn’t at all content during his short life with the fortune he’d made. He was always seeking ways to do things better and to expand the empire he began in Lost Cabin.

When a disastrous winter led him to send his sheep to Mexico to graze there instead, he ended up buying Piggly Wiggly franchise in Mexico, which included six stores.

The sheep transport idea proved a bust. He quipped that he not only had to hire sheepherders there, he had to hire men to watch the sheepherders and then other men to watch the men watching the sheepherders.

He ended up selling his herd at a loss. But the Piggly Wiggly stores were a big win, and more than made up for that loss.

Okie also has an impressive list of firsts to his name. He brought the first steam sheep-shearing plant to the United States in 1894.

“Right across the creek over here, there’s an old sweat shed,” Fross said. “What they would do is they’d bring the sheep in and put them under the shed overnight. That would pull the lanolin out into the wool. You could increase the weight of that fleece 10, 15, 20 percent by putting them in that shed overnight.”

Okie also built a warehouse to store his wool, noticing that sheepmen all tended to sell their wool at the same time, depressing the prices. He would hold onto his wool and sell it later, when the price had improved.

Okie tried to talk his fellow sheep ranchers into building a $10,000 wool-scouring plant in Casper, which would have increased the value of wool before it went to market. Reducing the debris in the wool would have also lowered the wool’s weight, saving money in shipping costs. The wool-scouring plant didn’t catch on.

But, when the tariff on foreign wool was revoked in 1913, Okie built an Australian sheering shed, which is still standing in Moneta, to better compete on the world market.

He also hired Basque sheep breeders, recognized as the best sheepherders in the world, to run his flocks.

They were in such great demand, only the best operations could afford them. Okie had a big advantage — he was a world traveler and could afford to bring his Basques in directly from northern Spain. He also spoke several languages, so he could talk to his herders directly.

Okie recognized the value of learning foreign languages. His children, who were all homeschooled, had to learn a foreign language. He would then send them to the country of their chosen language for at least six months, to ensure they were fluent.

He Had A Car

Okie had the first car in central Wyoming. When he built his mansion, it had a carbide-based electric system, likely also a first for central Wyoming, if not the state. A little moisture on the carbide produced acetylene gas, which would burn clean and produce lights for the mansion.

In one of the living room areas, there are green-fringed glass beads original to the house, along with the original green paint, Fross said.

“Imagine having that light send the glow of green through those beads,” he said. “The ambiance in this room must have been kind of incredible.”

Incredible, too, is the mansion itself, built in the high plains desert with running water in the year 1901. Okie was the home’s architect, Fross said, but employed French masons to cut the stone for his mansion and carpenters who framed the home using pine wood he had hauled in by freight train.

“Some people said he was crooked,” Fross said. “But I really don’t see that. To work for J.B. Okie was a coveted thing. He had that bunkhouse that looked like a depot. He had a pool table there for all the people to play pool. And they had beds in there that didn’t have bugs. That was a big plus. To work for Okie was a valued thing, a treasured thing.”

So, too, is the chance to keep up Okie’s mansion, Fross told Cowboy State Daily.

“I love this old girl,” he said. “She’s definitely worthy of our respect. What Okie did here was phenomenal really. And for Wyoming and the time period, way ahead of his time.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.