Much has been made about wolves either being environmental saviors by bringing balance to ecosystems, or essentially being an environmental wrecking ball by killing way too many elk.

Neither view is particularly true, a Wyoming wildlife researcher said Thursday.

Wolves do cause the much-vaunted trophic cascade “sometimes,” and also can “sometimes” significantly decrease the population of prey species such as elk, said wildlife researchers and avid outdoorswoman Kristin Barker.

Trophic cascade refers to the interactions between predators and their pray, a wildlife tickle-down effect, so to speak.

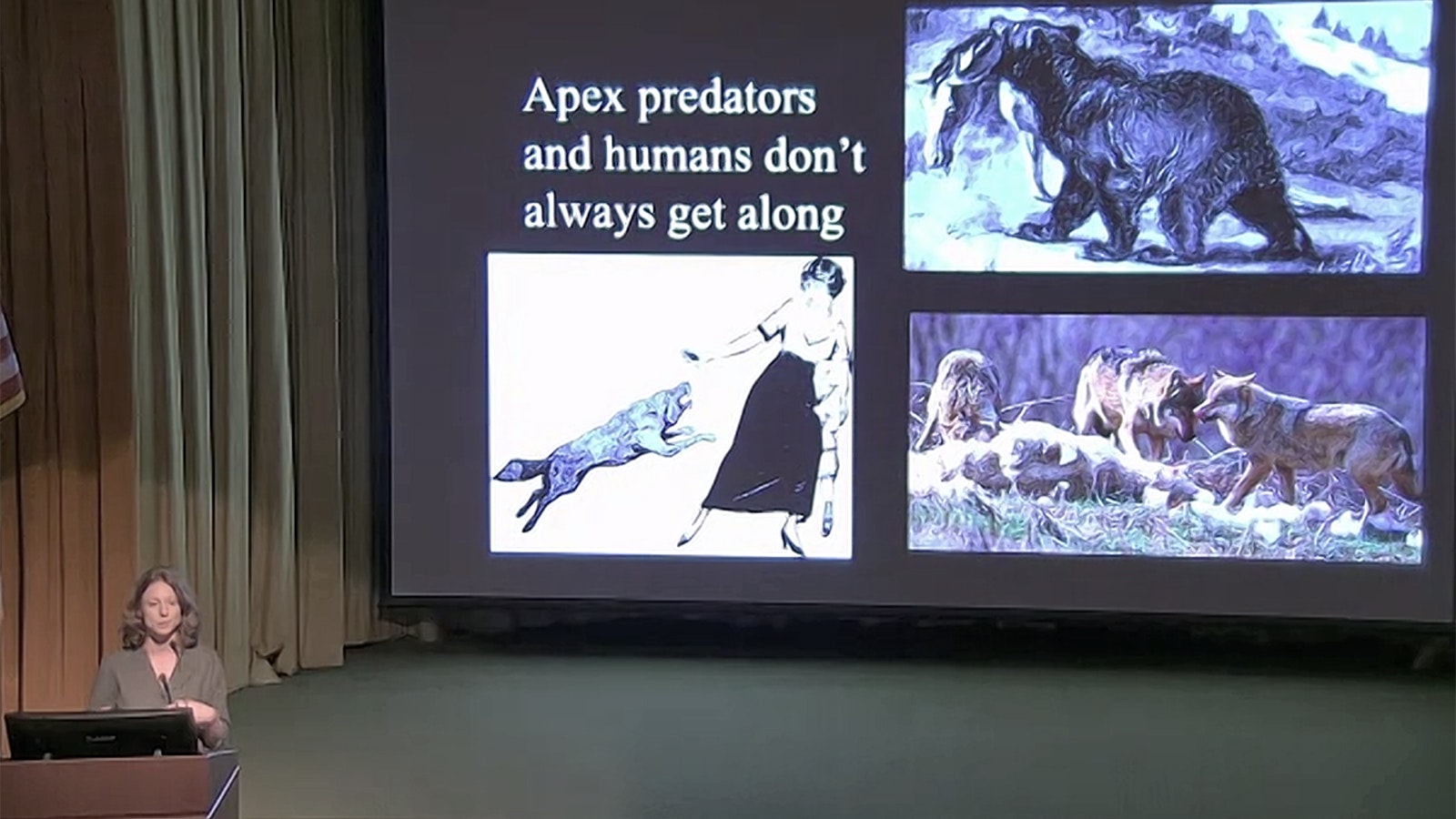

She made her remarks during a presentation about the complex interactions between wolves, elk and people at the Draper Natural History Museum in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody.

Her talk was titled “Who’s the Big Bad Wolf Afraid Of: Wolf-Elk Interactions Across the Wildland-Urban Interface.” It covered some results of winter research conducted in the Jackson area.

‘Trophic Cascade’ Idea Doesn’t Hold Up

Trophic cascade refers to the effect the return of an apex predator, such as wolves, can have in re-balancing an ecosystem. In Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding region, there have been many claims that wolves helped restore an ailing ecosystem.

The argument is essentially that an over-abundance of elk congregating in certain areas destroyed key vegetation – such as willow stands – which in turn drove out other species such as beavers. With the beavers absent, the course of many streams was altered in a way that hurt the ecosystem and hampered even more species.

The return of the wolves to Yellowstone in the mid-1990s knocked the elk population back and got the herds moving around more. That in turn, allowed the beavers to return to renewed willow stands and started a “cascade” of positive changes to the entire ecosystem, proponents of the idea argue.

While that certainly did happen in some areas, there’s no evidence of any such effect across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Barker said.

Nor is there evidence that wolves cause the widespread destruction that some claim, she added. There’s no reason to think wolves are either the “angels” or “demons” that different sides of the debate have tried to make them out to be.

Jackson An Ideal Place To Study

An ecosystem-wide summary of the effects of wolves is a gigantic and ongoing scientific undertaking. Barker said she and her team wanted to zero in on some specifics, particularly how the interactions between humans, wolves and elk play out.

And the Jackson area in the wintertime was perfect for that, she said. It has a large population of elk, along with wolf packs that hunt them along the edges of areas developed by humans.

There are other variables in play, such as humans hunting some of the elk herds. And there are some places near Jackson where wolves may also be hunted by humans and other areas nearby where hunting wolves is forbidden.

And there are numerous wolves and elk that have been radio-collared in the Jackson area, making the animals’ movements and interactions easier to track, she said.

They focused on roughly 170 wolf-kill sites around the area. Those consisted mostly of elk brought down by wolves, although there were a few moose, Barker said.

One question is, does human activity drive down the risk to elk of being killed by wolves, or does it increase it?

As with many factors when it comes to wolves, the answer is that it depends, Barker said.

Driven By Their Appetites, But Still Smart

It often comes down to both wolves and elk letting their stomachs make their decisions for them, but both species are also apparently much smarter than people give them credit for.

When food is plentiful, both species prefer to play it safe. Wolves will avoid hunting elk too close to human-inhabited areas, and elk will travel and browse in areas where it’s harder for wolves to stalk and attack them, she said.

However, in many instances, elk would hang out in “risky places” for wolf predation, if the winter forage was good there, she said.

Evidently, “the cost isn’t worth the benefit” for the elk when it comes down to selecting an area that might have less forage but a greater risk of being attacked by wolves, she said.

And elk also seem to have individual personalities, with some being far braver than others.

“Some individual elk just might have a higher risk tolerance than others,” she said, adding that wolves will reduce the risk to themselves, if the eating is still good.

For example, they will frequently hunt elk along hiking or snowmobile trails – which elk use – but only at night when humans are far less likely to be around, she said.

Wolf packs also tend to avoid roads, because vehicles are more likely to be there at all hours. And the wolves might have also figured out that hanging out around roads comes with the risk of being hit by vehicles, Barker said.

Wolves Will Kill Healthy Elk

It’s also a common assumption that wolves kill only old, sick or weak animals. Barker said that’s true, to an extent.

In general, the packs around Jackson seemed to prey primarily on very young or very old elk because they’re easier to chase down and kill, she said.

But she added her team was surprised by the number of “healthy elk of breeding age” they found killed by wolves.

That frequently boiled down to wolves being crafty, or those particular elk being a little stupid, she said.

Large, healthy elk are “targets of opportunity” for packs, she said. The wolves would wait until such elk were in good ambush spots that left their prey at a disadvantage.

“They were in really gnarly places where the wolves could just nail them,” she said.

Part Of The Ecosystem

Researchers have likely just scratched the surface of the complex interactions between elk herds, wolf packs and people, Barker said. But it’s evident that polarized opinions about wolves — either good or bad —are probably off base.

“Wolves are just another species that has co-evolved with other species that make up the ecosystems we see today,” she said.

Mark Heinz can be reached at mark@cowboystatedaily.com.