SAVERY — It’s a truck that’s seen better days. But Lela Emmons, executive director at the Little Snake River Museum, wouldn’t dream of touching up the little Crosley pickup’s paint job.

The rust spots and the varying colors of paint are all part of the Crosley’s charm, as well as part of a history in the Little Snake River Valley that will remain forever young at the Little Snake River Museum.

The pickup’s story is told in a side placard written by Barbara Moss, who was a girl of about 9 years old when her father, Hap Henderson, got the little Crosley pickup running again.

No doubt, he gave it a new coat of paint, or perhaps not — he was after all a ditch rider at the time, and that was rough work. No need for a pristine pickup. Ditch riders kept weeds and willows out of irrigation ditches, ensuring that they didn’t get jammed up, causing unintentional flooding.

Moss fondly recalls riding in that truck on a very hot summer day all the way to Craig, Colorado, some 50 miles away, with some of her cousins.

Her mom and her mom’s sister were in the front, while all the kids piled into the tiny bed of the pickup.

“The little truck was so hot we could hardly touch the sides,” Moss recalled. “So, there we sat, four or five little kids in the back of this tiny truck. Of course, us kids thought this was wonderful.”

Moss’ memory and the truck are just one of hundreds of little stories preserved at the Little Snake River Museum, where Emmons and other volunteers have become quite skilled at taking remnants from the past and weaving them into timeless stories of the valley, preserved for future generations.

The Baker Cabin

The Little Snake River Museum is a collection of buildings arranged as if they are a village of old. There’s about a dozen log homestead cabins ringing the campus, as well as a newer structure that houses an exhibit about Savery’s sheep industry. Many have proclaimed the museum is one of the best they’ve ever seen.

“Guests tell me that all the time,” Emmons said. “’We’ve traveled the world, and this is the best museum we’ve been through.’ We get that a lot.”

Perhaps the most significant building in the collection is Jim Baker’s cabin. Baker was one of the last mountain men of the West, and a man who was prominent in both Wyoming and Colorado.

Baker was hired by famous mountain man Jim Bridger for John Jacob Astor’sAmerican Fur Company. As a trapper for them, he went all over the Rocky Mountain West. When he was ready to retire from “big city life” in Denver, though, his choice for a slice of heaven was Savery, Wyoming. He built a two-story cabin — a miniature fortress really — which he lived in until his death in 1898.

Sometime after his death, Baker’s cabin was caught up in a little tug of war between Wyoming and Colorado. The latter had immortalized Baker with a stained glass window in that state’s capitol, highlighting him as an important figure of the West and their state. The folks in Colorado wanted Baker’s cabin as part of that history.

People in Savery, however, appealed to the Wyoming Legislature to keep the cabin in Wyoming. That resulted in legislation that landed the cabin in Cheyenne in 1917. Not exactly the solution that Savery residents had hoped for, but at least the cabin remained in the Cowboy State.

Eventually, once the frenzy over the Baker cabin was forgotten, it landed in storage for a long time. Decades passed, and then, finally, it was returned home to Savery in 1976.

No Numbers To Go By

The cabin arrived as a pile of logs. The numbering system placed on the cabin’s individual logs when it was disassembled had long ago faded, so it took a fair bit of tenacity and ingenuity to put everything back together again.

Frank Duncan, a carpenter and artist from Dixon, created a miniature replica of each and every log. He tinkered with the replica logs arranging and rearranging them a bit like a child might a Lincoln log set. Finally, after much trial and error, he had a model made from his replicated logs that looked just like old photographs of the cabin suggested it should.

From there, he and other volunteers, including Baker descendant Paul McAllister, were able to put the real logs back together as the two-story cabin it once had been.

According to historical records, Baker may have had a third turret on his cabin, which was a lookout tower, when it was first built. There are no pictures proving that, however, and historical documents suggest Baker himself soon disassembled the lookout tower as tensions with American Indian tribes waned, so the cabin was left as two stories.

It now sits a mile from the original location when Baker occupied it, and it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Baker’s gun is on display in the Little Snake River Museum collections, which are housed in what used to be the Savery schoolhouse. There’s also a couple of Baker’s clocks there.

The cabin itself is outfitted with period furniture and furs, as well as portraits of Baker and other historical artifacts representing mountain man history.

Baker also built a couple of homesteads for his daughters, which are also still standing and part of the Little Snake River Museum.

A Story For Every Cabin

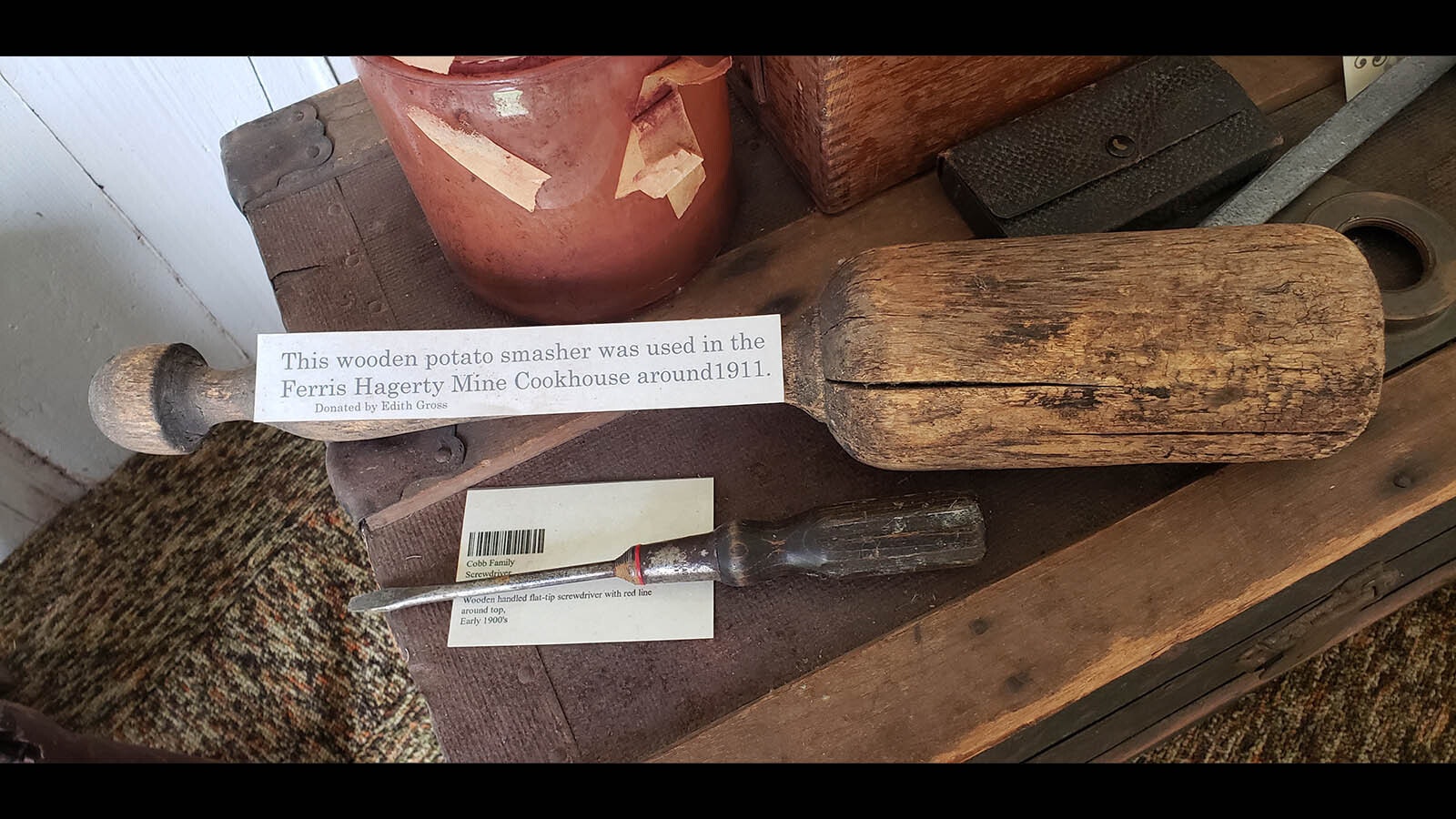

Every item inside the Little Snake River Museum has a story that’s tied to the history of the valley in which the museum sits. That’s part of the museum’s charter, in fact. Every item must be tied to the valley in some way.

Likewise all the cabins, too, have their cool and interesting stories, which are being preserved.

Among them is the Stonewall Cabin, built in 1871 by Bill Slater and Bibleback Brown, just 2 miles from its present-day home at the museum.

The cabin was given to a family down on their luck, counting the last of their change with a couple of children in tow, Emmons told Cowboy State Daily.

“They ended up staying to become one of the big ranching families of the valley,” Emmons said. “The Reader family, Noah and Rossanna. Their descendants are still around.”

Noah’s wife, Rossanna, was a trained herbalist and healer who befriended many of the American Indians living in the valley at the time.

She was the first white woman to call the Valley home.

“She went like seven years without seeing another white woman,” Emmons said.

The cabin has been set up to represent a typical trapper home for the late 19th century, complete with a sod roof. It, too, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the future, Emmons wants to plant a medicinal garden around the cabin, to represent the kind of plants Rossanna would have worked with at the time.

Saving History

While many of the Little Savery Museum’s buildings are largely intact when they arrive, some are not. Emmons is never daunted, however, when it comes to rescuing the bones of good history in the Little Snake River Valley.

“Sometimes, you kind of have to start from scratch,” Emmons said. “You may have to replace some logs on the bottom .. stabilize them, sometimes put a completely new roof on the structure.”

And with some, preservation starts with a bit of demolition first. The Focus Cabin, for example.

“I helped tear the old wall board out and get it ready to disassemble,” Emmons said.

Then a specialist came and single-handedly took it apart, salvaging as much as possible from the cabin.

Since a picture window had been cut into the cabin in the 1970s, and a big fireplace added to the living room, that particular cabin couldn’t be restored to the story and one-half that it used to be.

“He could sort of see on some of the logs where the floor had been,” Emons said. “So he figured out what size of cabin he could get and got some historic windows to put in there, because all the windows had been replaced with newer windows so they weren’t authentic.”

That particular cabin had also been through multiple transformations, Emmons added.

“It’s kind of a fun one, because it also came to the Focus Ranch from somewhere else years ago,” she said. “And they don’t even know when it came, it was like dragged down from some mountain, you know, some other ranch. They did a lot of that, moving cabins around in the old days.”

The cabin was transformed into a guest cabin for help in the summer on the Focus Guest Ranch and was built somewhat into a hillside.

“Normally, we don’t do anything like that where, you know, we totally transform it from what it was,” Emmons said. “But it had been altered to the point there was no saving it as it was.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.