The grave of an Indiana woman who died in 1862 near La Barge is a stark reminder of the hardships faced by westward-migrating pioneers and is part of a much bigger story about where the Oregon Trail crossed Wyoming.

The Lander Cutoff was the first federally funded wagon road built in the West. It begins at Burnt Ranch near the Sweetwater River a few miles south of South Pass and traverses 256 miles across southcentral Wyoming to Fort Hall, Idaho. It crosses Thompson Pass near La Barge in the Wyoming Range and was an alternate route for emigrants that was shorter and avoided Utah’s west desert, which was devoid of grass and water.

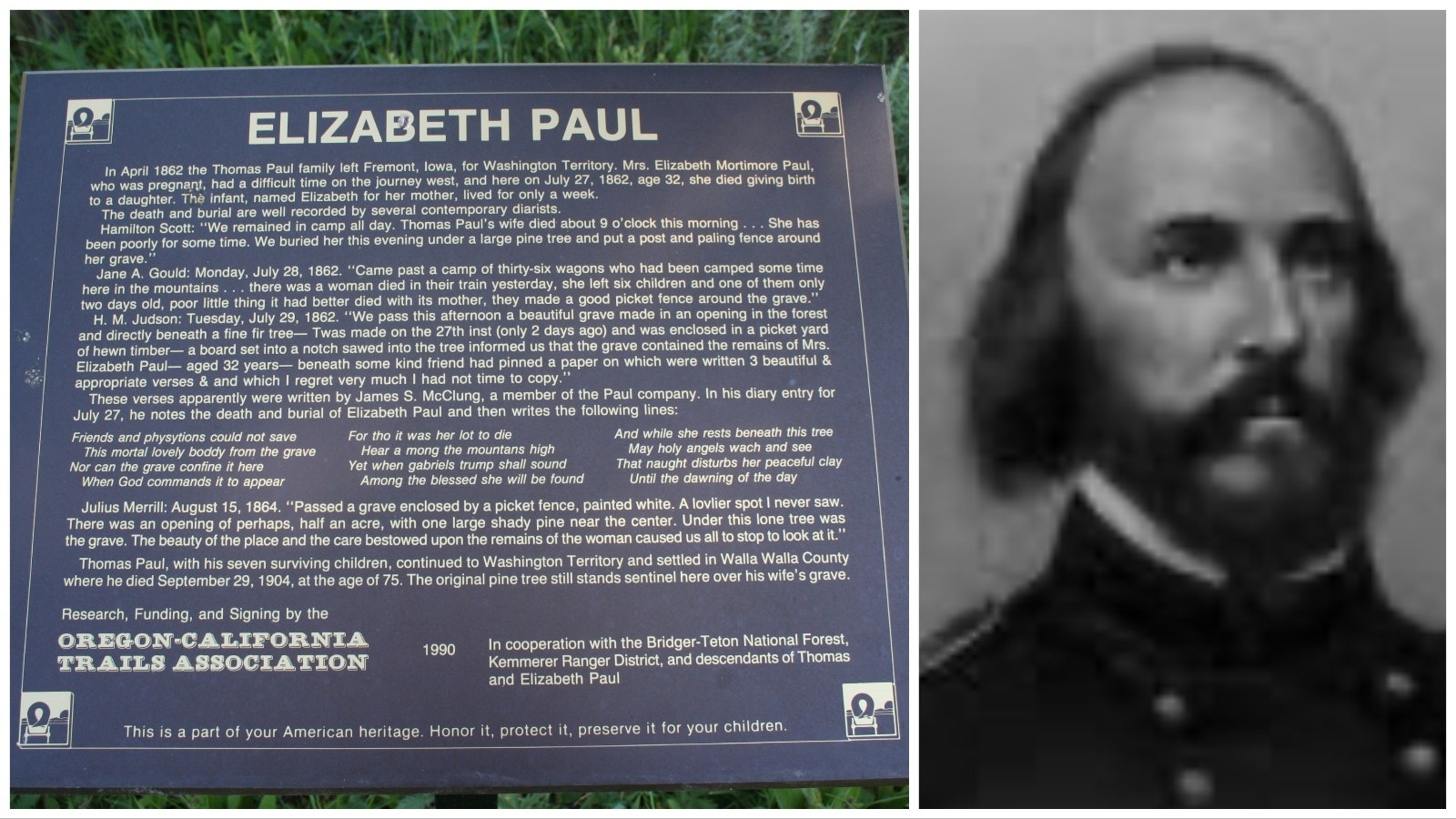

The gravesite of Elizebeth Mortimer Paul is located a few miles up the La Barge Creek Road on the way to Thompson Pass in a meadow beneath a lone pine tree. She was 32 years old, a mother of eight children and died during childbirth. Her baby, a girl, died a few days later and was buried near Gray’s Lake, Idaho, according to research compiled by historian Robert Kominsky of Kemmerer.

The site was memorialized by the Oregon-California Trails Association. A ceremony attended by an estimated 100 historians and relatives of Paul was held in 1990.

Deaths were frequent along the California-Oregon Trail, especially along the Lander Cutoff portion of the trail, according to Kominsky's research. About one in 17 adults died during their journey West and one in five children met the same fate. Nearly 80 pioneer-era graves have been found roughly between Big Piney and La Barge, a distance of 25 miles.

Dousing with ‘Witch Sticks’

In 1997 while serving as a tour guide for the Oregon-California Trails Association, Kominsky said, he met a man from Kansas who knew how to find graves by holding a bent welding rod in each hand.

When the tour stopped at a marked grave near Big Piney Creek, the man held the welding rods out parallel to the ground and walked slowly around the marked grave. The rods crossed near the grave, and the man told Kominsky there was a second grave there.

Later that day the man identified several other graves, Kominsky said.

“I didn’t believe him, so I said let’s go down to Coal Creek where a 6-year-old girl drowned when a wagon tipped over,” Kominsky wrote. “This time I watched him very closely. Pretty soon the welding rods moved on their own and pointed to a rock pile. He said her grave is right there. After watching him very closely I became a believer.”

Using “witch sticks,” also known as “dousing,” to surface locate groundwater, minerals, ores, oil and graves has been practiced for hundreds of years. Some believe it works, while others consider the practice questionable.

The West’s First Federally Funded Road

In 1857 Congress authorized $300,000 for the Fort Kearney-South Pass-Honey Lake Wagon Road, which later became the Lander Cutoff. Where to cross Wyoming on the way to points farther west was competitive and controversial. Kominsky’s research states that wagon travelers were bilked at every available opportunity.

The Lander Cutoff was routed around Mormon Territory to avoid religious bias and the harsh deserts west of Salt Lake Valley, and to dodge pasturing fees and other costs associated with crossing private land in what is now Utah. Emigrants were charged from five to 25 cents per day per animal and rumors still persist that some emigrants were not sold supplies unless they converted to Mormonism first, Kominsky’s research says.

Ferry Crossings on the Green River, the New Fork River and others were a significant source of revenue. Jim Bridger, the famous mountain man, guide, trapper and scout and his partners grossed over $300,000 in one year from a ferry on the Green River at Names Hill near La Barge. They charged from $3 to $6 for each wagon, according to Kominsky.

The ferries were a solid source of income to their owners who resisted plans to build bridges that would replace them. Frederick Lander, who the town of Lander and several other Wyoming landmarks are named for, scouted and planned the Lander Cutoff route. When he asked Congress for money to build a bridge across the Green River, he was refused. According to Kominsky, he was turned down due to fear the bridge would be destroyed by the ferry owners.

“Of course, for every wagon that used the Lander Cutoff, that meant a loss of money at the ferry locations and other business enterprises at Fort Bridger, in Salt Lake City and elsewhere along the main Oregon Trail,” Kominsky writes.

Frederick Lander and Chief Washakie

Chief Washakie, a Shoshone Indian was considered a great chief, and is the only chief to be buried with full military honors. According to Kominsky, during a battle with Crow Indians that occurred near Crowheart, Wyoming, when neither side could make headway, Washakie challenged the Crow Chief Big Robber to a hand-to-hand battle.

Washakie killed Big Robber, cut his heart out and ate it. Allegedly. Later in his life when a reporter asked if the story was true, Washakie would neither confirm nor deny the story. The place where the battle happened is now called Crowheart Butte.

According to a second historic account of the battle reported by Cowboy State Daily in April, Chief Washakie killed Big Robber and rode his horse back to his tribe carrying Big Robber's heart on the tip of his lance.

James Trosper, head of the Chief Washakie Foundation and direct descendant of Washakie told Cowboy State Daily the story was passed down through his family - and the Crow chief's heart was not consumed.

Frederick Lander was born in 1822 and became a civil engineer. He negotiated with Chief Washakie and provided firearms and supplies to the Shoshones in exchange for safe passage across the Lander Cutoff.

While mapping the Lander Cutoff he traveled 3,000 miles on horseback and explored 16 mountain passes before deciding on Thompson Pass as the safest way through the Wyoming Range, located in Sublette and Lincoln counties.

The Lander Cutoff was completed in 1858 at a cost of $67,873. Wagon trains could travel about 13 miles per day and the new route saved the wagon trains about seven days as compared to the main Oregon Trail. Lander’s writings indicate there were about three people and 12 head of livestock associated with each wagon that crossed Wyoming, according to Kominsky’s research.

The road was constructed by a crew of 115 men, some of whom were Cornish miners sent by Brigham Young. In 1859, 13,000 people used the Lander Cutoff.

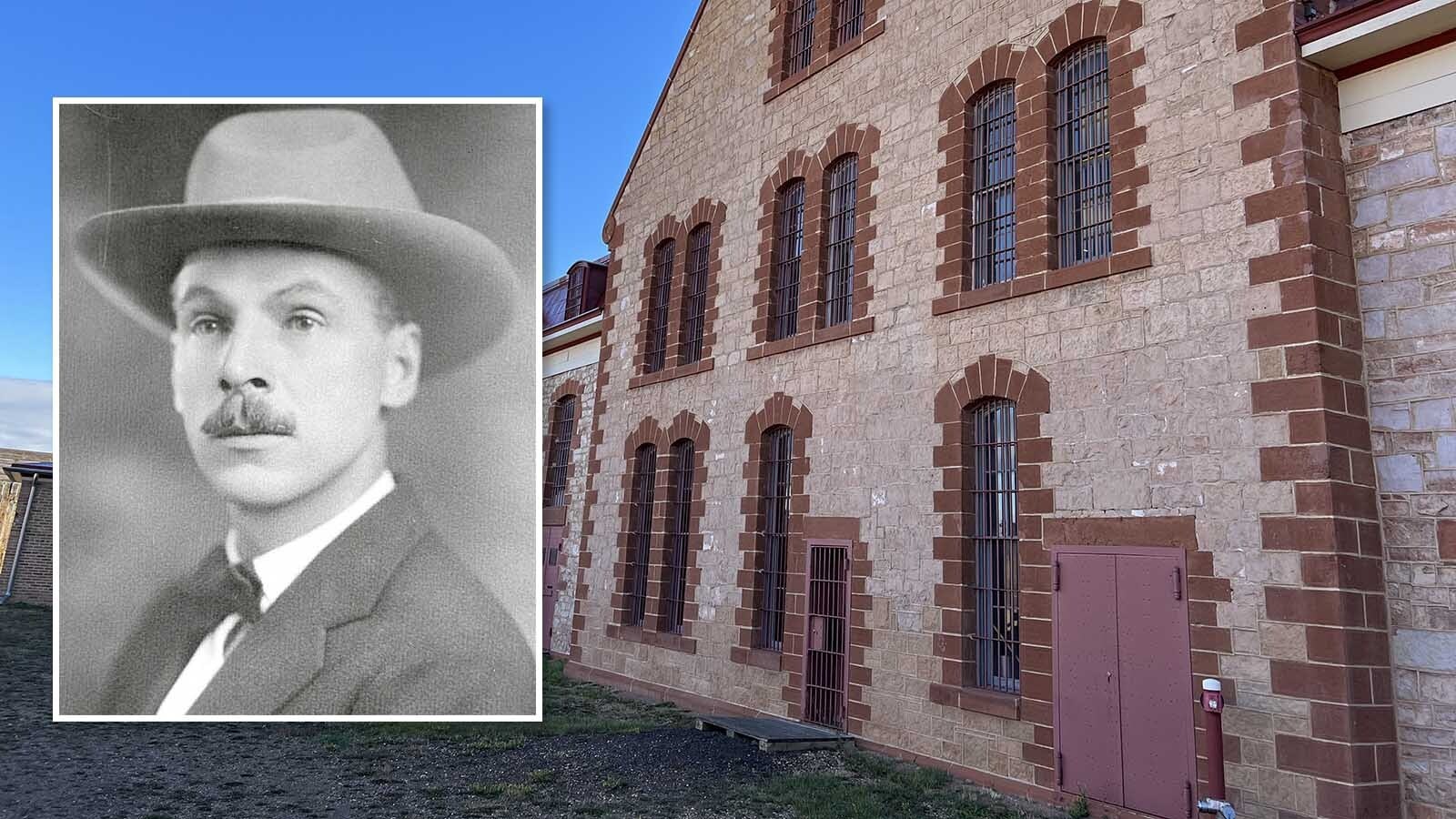

Lander later served as a brigadier general in the Union Army during the Civil War. According to Kominsky, there are two conflicting reports of Lander’s death. One states he died of pneumonia in 1862. The other states he died in 1864 as a result of wounds he suffered in a Civil War battle.

In one of his reports Lander describes the Lander Cutoff as “abundantly furnished with grass, timber and pure water. … An excellent and healthy emigrant road, over which individuals of small means may move their families and herds of stock to the Pacific Coast in a single season without loss.”

John Thompson can be reached at: John@CowboyStateDaily.com