Editor's note: This story was first publised Sept. 2, 2023, to commemorate the 49th anniversary of the famous stunt. It's reposted here to mark its 50th.

As this Labor Day weekend brings with it the anniversary of Evel Knievel’s failed jump over the Snake River Canyon in Twin Falls, Idaho, Cowboy State Daily drills down on a man whose life trajectory followed that of his jumps.

From dust to dust, Knievel was a man that rocketed to celebrity, peaking as a legend in his own time, and just as quickly came crashing back to earth.

For a time, no one was bigger. Not Elvis, not Sinatra, not the Beatles. Nobody did the TV numbers this daredevil from Montana did.

Knievel’s fame was part novelty, part bravado and fluky timing. The country had not seen a showman quite like Knievel — a big talker with even bigger balls who became a real-life superhero (complete with the cape) in red, white and blue.

And he couldn’t have arrived at a better time. The late 1960s saw America in turmoil, much like today. The Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and antiwar protests, countercultural movements, political assassinations and an emerging generation gap threatened to tear the nation apart.

Along comes a hard-bitten kid from Butte with the swagger of John Wayne. He’s flawed, sure, but he’s fearless. He fails, a lot, but he keeps getting back up.

He kickstarts our hearts and fills America’s hope chest pulling wheelies. He captivates a nation on the brink of imploding.

Collectively, we stop worrying life for a moment and hold our breath as this cycled crusader hangs in the air suspended over a row of parked buses.

“Good Lord, he’s not going to make it. He’s going to come up short.”

Knievel is so impactful, so larger than life, it’s difficult to measure his contribution to American culture. He invented reality TV before its time. At the height of his notoriety in the mid-1970s, Ideal couldn’t keep his Stunt Cycle toy in stock, selling some $300 million worth. Forget Ken, G.I. Joe or even Barbie.

Every boy in the USA wanted to be Evel Knievel.

Snake River Jump

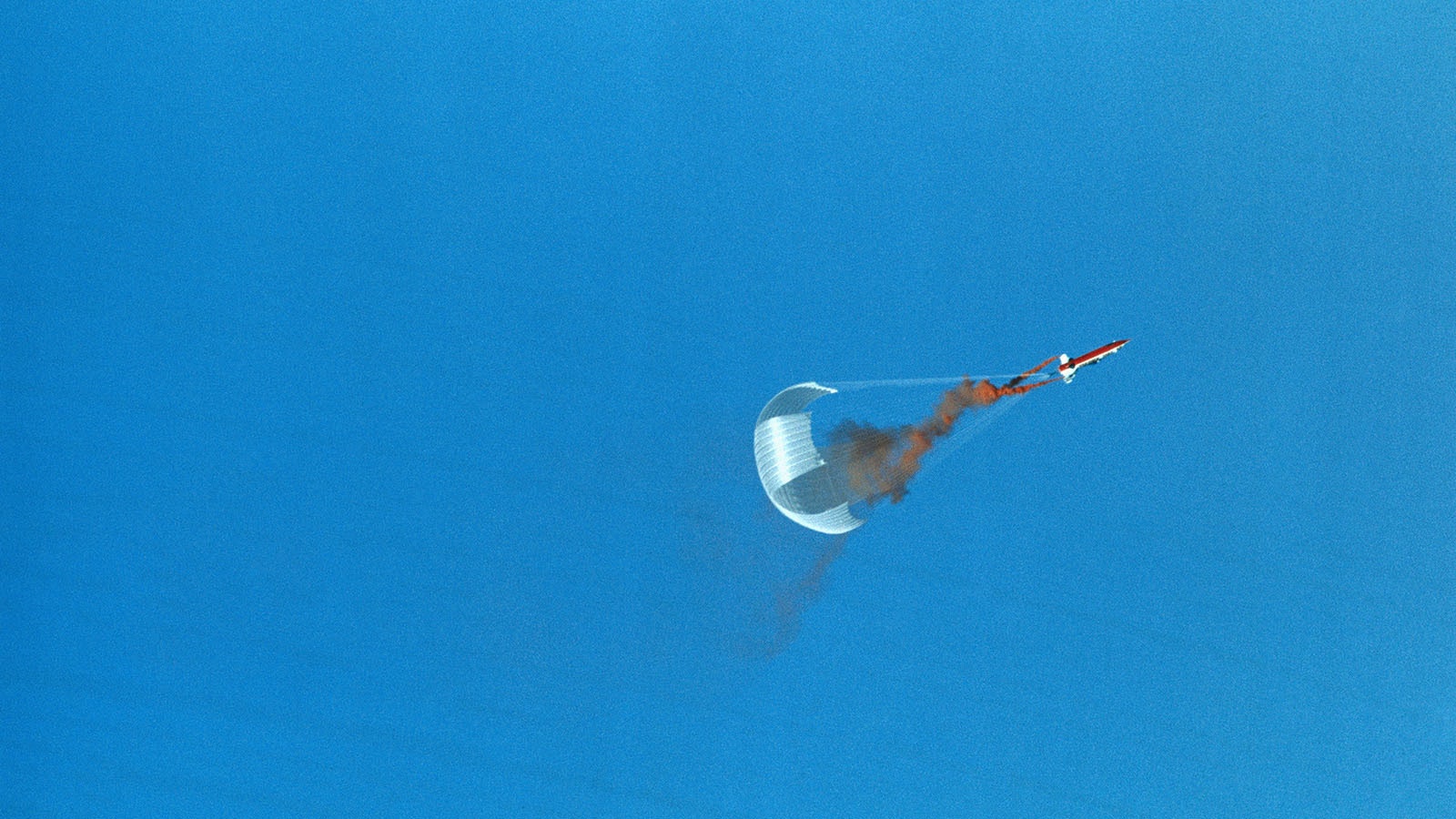

It’s Sept. 8, 1974, and Evel Knievel sits in a pressure cooker aimed at the Idaho sky. His Sky-Cycle X-2 is a 16-foot-long customized rocket, powered by steam.

The plan?

A water tank with wings is heated to 600 degrees, the cork is pulled and, whammo, the whole shebang will be doing 350 mph in seconds and headed for the far bank of the Snake River a quarter mile away.

Television crews and reporters came from everywhere to cover the event. It’s two days of lascivious tailgating that would make the Romans blush. The National Guard was called. They couldn’t come, so Hell’s Angels were paid to keep the peace — the fox in the henhouse.

Beer trucks were overturned and locks shot off. Port-a-potties set on fire. As high school marching band, along with the Purple Bees drill team from Evel’s hometown of Butte, Montana, are harassed to no end. It’s bedlam.

“It was so audacious, so daring; you were going to watch a guy kill himself,” remarked TV icon Geraldo Rivera at the time.

An estimated 33,000 people turned Twin Falls, Idaho, into a macabre Woodstock. They were whipped into a frenzy by skillful marketing from Knievel’s longtime promoter, Shelly Saltman.

Prior to the jump, Saltman arranged a 30-day promotional tour with 90 airport stops. Bigger preshow hype than any Ali fight, and Saltman would know, he promoted them all.

The tour coordinator for The Who was hired to make sure everything ran smoothly.

Nothing was going to get in the way of Evel’s jump over the Snake, not even the Secretary of the Interior. When Stewart Udall denied Knievel permission to jump the Grand Canyon, the famed daredevil said, “Then I’ll buy my own canyon.”

And he did. Knievel bought 425 acres outside of Twin Falls on the rim of the Snake River Canyon where the takeoff ramp was constructed.

Three separate rockets were built to spec by Aerojet engineer Robert Truax. A few weeks prior to launch, Knievel’s team tests one. The unmanned rocket spurts out well short of the opposite canyon rim and plunges into the waters of the Snake River.

The media was horrified into worry. But what no one knew was the rocket was intentionally underpowered. It was meant to fail. More build-up from the master of hype. Another stunt from the king of con men.

Knievel’s team begged him to try a real test with the second rocket. They did. It also failed, the chute deployed early and the ship nose-dived onto the river.

There sat Knievel in the hot seat, ready to risk life yet again, a life that many only dream about.

The Early Years

Robert Craig Knievel was born in Silver Bow County Hospital on Oct. 17, 1938. He was raised mainly by his grandparents after his parents split up.

Butte at the time was a tough-ass mining town. Knievel learned to stand up for himself. His cousin Pat Williams remarked in the documentary “Being Evel,” about young Robert’s chutzpah.

“He wouldn’t back down as a kid. You couldn’t dare him. If you dared him, he’d do it,” Williams said.

By high school, Knievel was raising hell on his motorcycle. Butte policeman Pat Burns remembered chasing him several times, unsuccessfully.

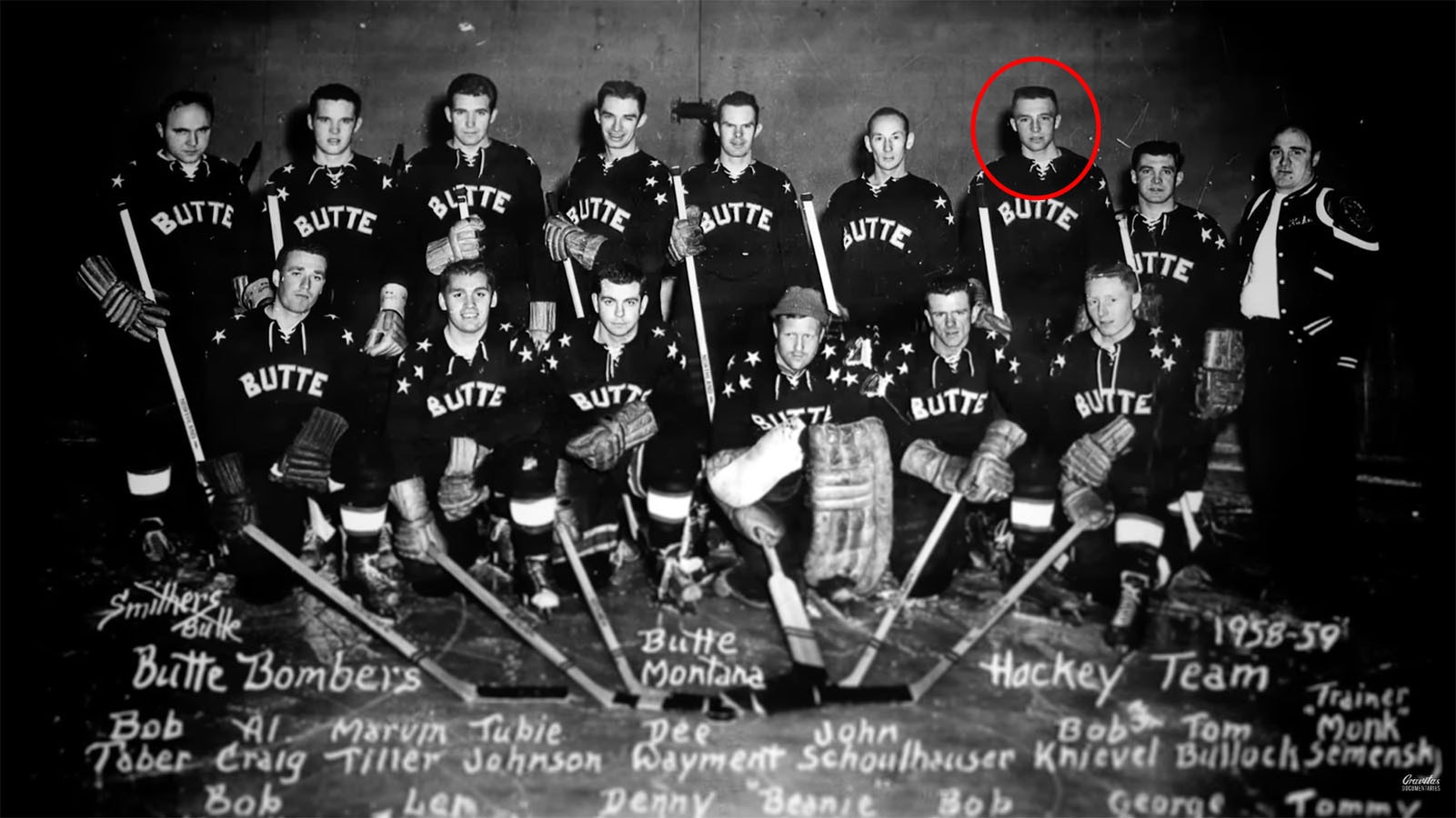

At age 19 and fresh out of high school, Knievel shows early indication of his promotional genius. After a brief stint with the North Carolina-based Charlotte Clippers minor league hockey team, Knievel returns home and starts his own semi-pro hockey club in 1959.

He somehow convinces the Czechoslovakian Olympic hockey team to travel to the U.S. and play his Butte Bombers in front of a reported 2,000 fans. The Bombers are smoked, 22-3. Knievel gets ejected in the third period, leaves the building with the Czech’s share of the gate receipts, and the U.S. Olympic Committee is forced to step in and make good.

Soon after, Knievel marries high school sweetheart Linda Bork on Sept. 5, 1959, by basically kidnapping her and driving her to Dillon to see a justice of the peace.

Odd Jobs

Following the birth of his first son, Kelly, Knievel started his own hunting tour business called the Sur-Kill Guide Service, where he guaranteed hunters would bag an elk or their money back. Knievel’s enterprise was hugely successful from the outset until federal authorities realized why. He was leading clients into Yellowstone National Park and poaching elk.

Undeterred by being caught, Knievel hitchhikes to Washington, D.C., lugging a 54-inch-wide antler rack to personally petition the Secretary of the Interior to stop the U.S. from culling elk within the park. Whether by his influence or not, soon after Knievel’s visit the U.S. adopted a new policy of hazing excess elk into Montana where they could be hunted legally — a practice that continues to this day.

By the time Knievel has three kids, he turns legit, taking a job as a door-to-door salesman for Combined Insurance. The slick-talking Knievel was a natural. He broke a company record by selling 271 policies in one week. Unfortunately, most of those were nullified when it was found he sold the bulk of them to patients at a nearby psychiatric hospital.

Knievel then moves the family to Moses Lake, Washington, in 1965 and opens a Honda Motorcycles dealership. To boost business a little, Knievel figures a publicity stunt would work, recalling Joie Chitwood and his traveling stunt show from his childhood. He proposes to do a motorcycle jump over cougars and rattlesnakes.

When Knievel’s 350cc Honda comes up three feet short, his back tire upends the crate holding the snakes and they catapult into a crowd of about 1,000. Everyone runs screaming. Knievel drives up the ramp and congratulates himself, arms raised high.

Career Underway

Knievel began immediately planning his next move. He befriends a bartender at Marty’s Bar in Orange, California, convincing him to foot the bill for a ramp-to-ramp jump over a couple of pickup trucks parked end-to-end.

Knievel also organizes his “Motorcycle Daredevils” team, which includes Swede Savage, Eddie Mulder and a little person named Butch Wilhelm who Knievel boasts will do whatever stunt he does, only on a miniature scale.

It’s in 1967 that Knievel also takes to using the name Evel for the first time. During a brief stint in the clink years prior, he was locked up with a man named William Knofel. During roll call, the jailer took to calling the pair “Awful Knofel” and “Evil Knievel.” Knievel changed the spelling so as not to appear too evil and his daredevil career took flight.

Some $52,000 in debt, the group eventually broke up and Knievel went solo. He performed several jumps in 1967 — landing some, crashing others. Still, he was far from a household name. As the end of the year approached, Knievel thought he needed something really big to get noticed.

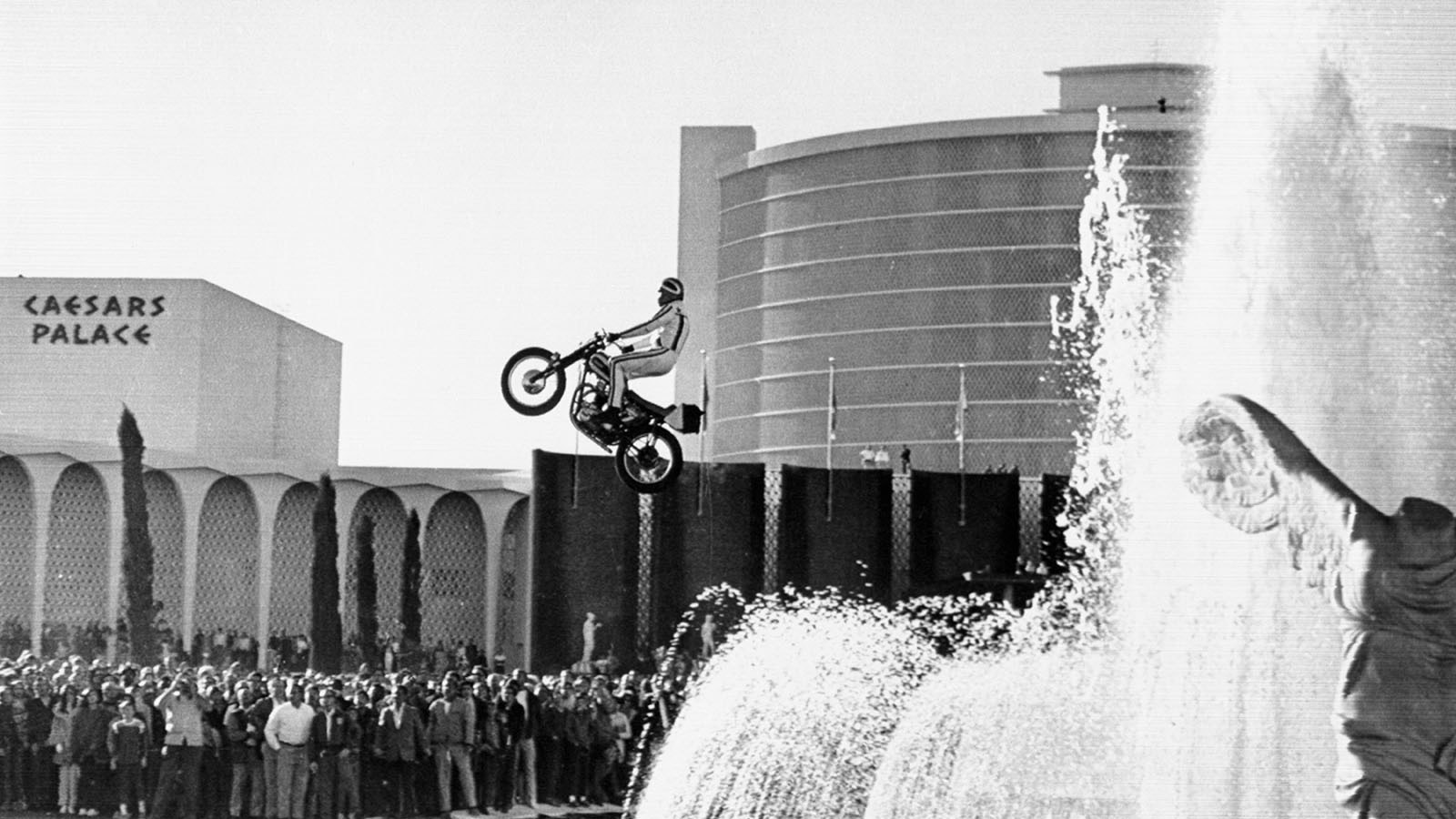

Caesar’s Palace Royal Flush

The showman scammed his way into a jump of the iconic Caesar’s Palace fountains by first inviting every media outlet he could think of to cover the event. He then started pestering casino CEO Jay Sarno, calling him every few days, changing his voice and claiming to be ABC, Sports Illustrated, whoever.

Initially Sarno thought it was some crackpot.

“Knievel? Never heard of him,” he reportedly said after the first few calls. But Knievel was so persistent and convincing, he soon had Sarno changing his tune.

“Yeah, I'm hearing a lot about this Knievel guy. Yeah, we got him booked here for a New Year’s Eve jump.”

ABC’s Wild World of Sports declined to air the event live but promised, if the footage was good, to run it eventually. Knievel enlisted director John Derek to film the jump, his wife on one of the cameras.

Had he made the jump, Knievel’s meteoric rise to fame might not have been nearly as spectacular. Crashing in an “agony of defeat” turned out to be the best thing the 29-year-old could have done.

The slow-motion shot of Knievel tumbling like a ragdoll 60 feet into the Dunes’ parking lot is still one of the greatest pieces of sports footage of all time.

Knievel broke both wrists, both ankles, fractured ribs. He was reportedly in a coma for a month but that was more fabrication than truth.

After recovering, Knievel hit the talk shows. During one visit on “The Tonight Show,” host Johnny Carson introduced him as “probably the only man in history who has become very wealthy by trying to kill himself.”

During that visit, Knievel doubled down on his superhero persona.

“I know I've been called a lot of things, like a con man. But when you barrel down that long white line you better have made your peace with God and know what you’re doing because a con man ain’t gonna get there,” Knievel said.

During another interview, when asked if he was ever afraid before a jump, Knievel said, “Let’s say I have some concern. But I don't think I've ever been afraid of anything.”

Gluttony Knows No Bounds

Knievel’s popularity skyrocketed during the 1970s. He was a regular on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, which ran weekly on Sundays for 37 years. Knievel appeared in seven of the show’s 10 highest-rated episodes.

George Hamilton starred in a movie about his life. A licensing deal with Ideal brought in millions of dollars. There were Ferraris, Lear jets, boats, mansions. Knievel’s appetite was reputedly insatiable.

“I'm risking my life for it, I'm going spend every damn dime of it,” Knievel told Dick Cavett on his talk show. The audience went wild.

Wife Linda stood by Evel as he caroused with women, sleeping with a reported 2,000 in total, a record eight in one 24-hour period.

For seven years Knievel rode the wave, but fame began eating away at him. Close friends around Knievel say he became paranoid, jumpy, flaky. He was losing his grip on reality.

“He was always reselling what he had already sold. How do you get any better, any bigger? He could no longer satisfy himself,” Hamilton told documentary filmmakers for “Being Evel.”

Evel Knievel had created a character. He never broke character. He broke only himself.

Knievel suffered a reported 433 bone fractures earning him an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records.

“Surgeons were amazed at how he kept going. He had recuperative powers that were beyond normal people,” Linda said. “He was told to wear a cast for eight weeks. He would take it off in three.”

“I've become immune to pain,” Knievel said in his heyday.

Back To The Snake River

To get permission from the state of Idaho to do the jump, the X-2 was registered as an airplane instead of a motorcycle. That meant the FAA had the right to ground all air travel in the vicinity during the actual jump, which the agency did. It’s the reason why there is no video of exactly where Knievel crashed even though three helicopters were on standby.

Minutes from launch, Knievel’s team tells him a 15 mph headwind is too much. He should delay. Knievel takes one look at the thousands gathered to see him jump and says he’ll go through with it as planned.

The failed launch was doomed from the start. The parachute deployed on takeoff — far too early and just as it had done on the test run — and immediately began slowing the rocket ship. As the craft twisted and rolled, Knievel could be seen struggling to free himself while the rocket plummeted into the gorge.

“He was trying desperately to get out of the Sky-Cycle,” one reporter commented on the live broadcast.

“I am very scared,” said another as tense moments went by.

Cameras captured Knievel’s wife and children huddled together, shrieking and crying.

At first it was speculated the rocket had splashed into the river. It would have been a death sentence for Knievel. He was strapped in tight.

“If I had gone in the river, I’d have never got out of it,” Knievel later said.

Volunteer rescuers in a raft were able to get to Knievel quickly and pull him from the rocket, which had landed on the rocky banks of the river, 10 feet from the water.

As the rescue raft came into view a network announcer blurts, “Evel Knievel is standing in the boat and waving. He is alive and well. Maybe he did not clear the canyon. Maybe his dream did not come true. But at least he is alive and well ... and he tried.”

The early chute deployment was most likely operator error. Knievel was to hold down a spring-loaded lever designed to open the chute once he let go. Unprepared for the G-force encountered at blast off, Knievel likely blacked out or simply had the handle slip from his grip.

Beginning Of The end

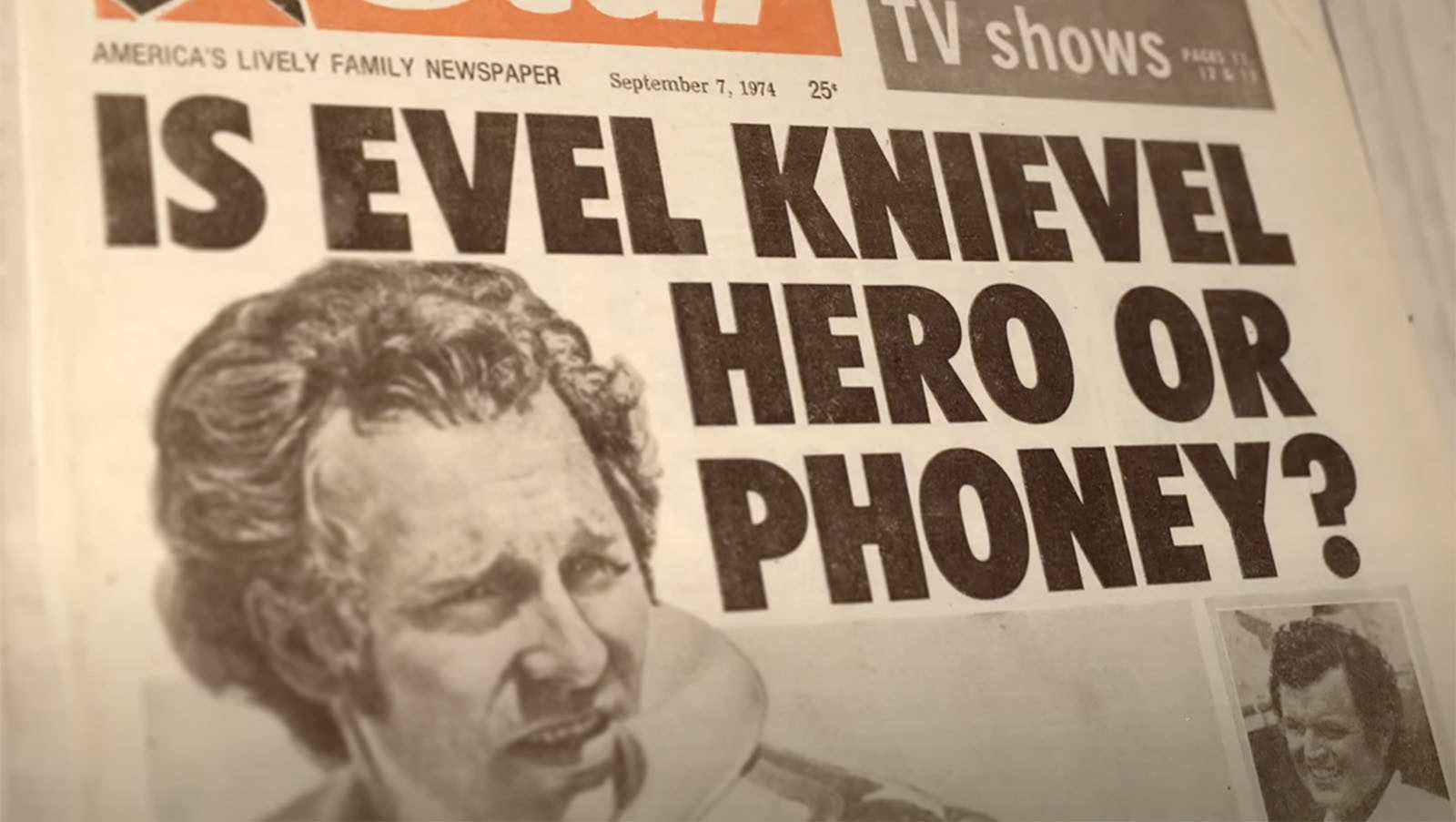

Knievel’s fall from grace was hastened by the failed Snake River jump. Not so much the jump itself, which earned him a reported $6 million, but his behavior during pre-jump interviews and subsequent pouting about media coverage post-jump, some of which questioned whether Knievel was a hero or hustler.

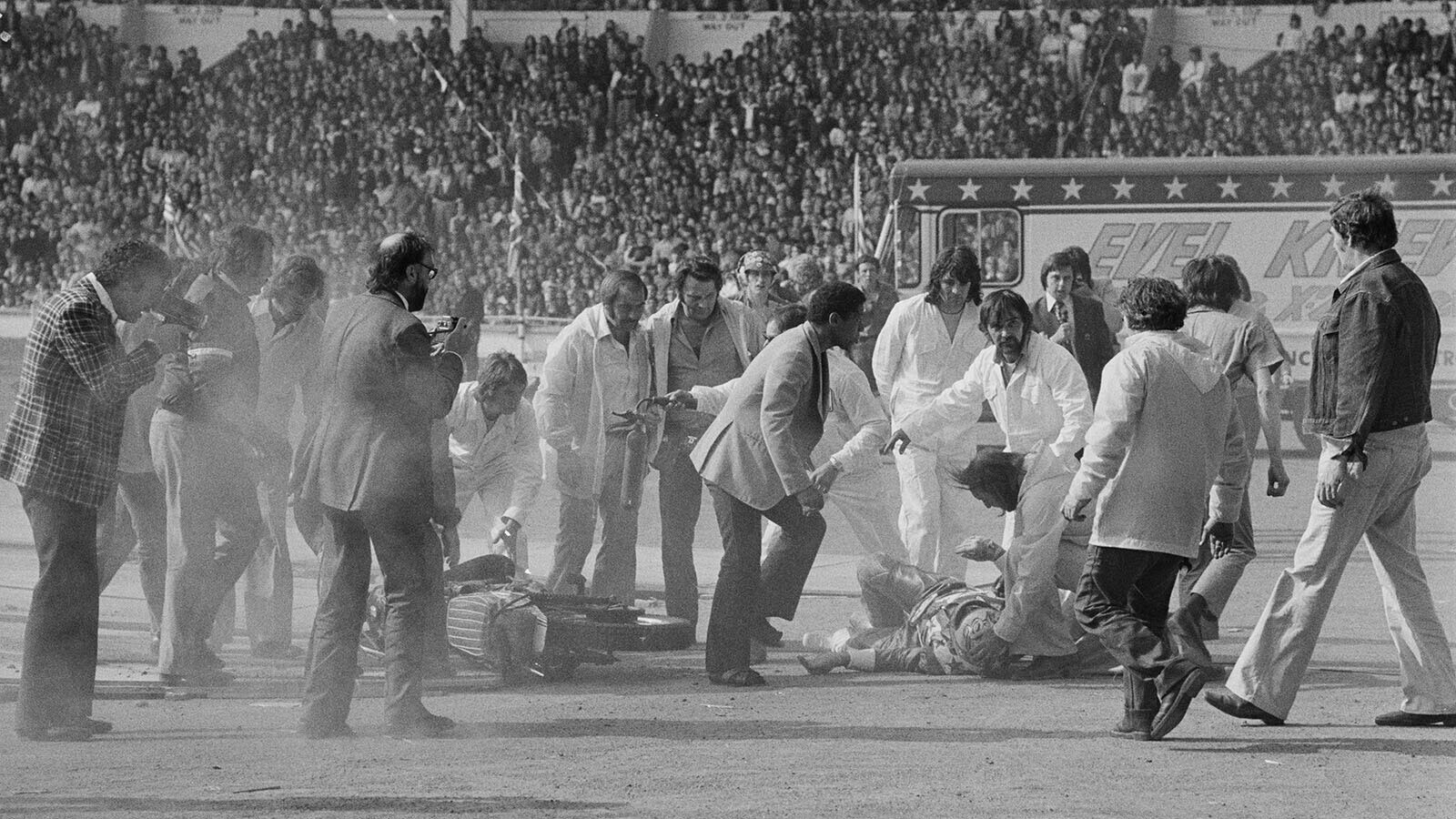

Depressed by the press, Knievel travelled to England to reenergize his career. Some 90,000 showed up in Wembley Stadium on May 26, 1975, to watch the daredevil attempt a jump of 13 single-decker buses. Twelve would have been better.

Knievel landed on the 13th bus and crashed spectacularly, his bike coming to rest on top of him. A mangled Evel struggled to his feet with assistance, walked to an open mic and announced that everyone in attendance had watched his last jump.

“I will never, ever, ever jump again. I'm through,” he said, in obvious pain with a broken pelvis.

But he wasn’t done.

Months later he planned his next stunt. Stating 13 buses was an unlucky number, Knievel vowed to jump 14 instead. His doctors warned against it saying he could not afford another mishap. At 133 feet it would be his longest successful jump if he nailed it. He did.

That Kings Island jump in Cincinnati on Oct. 25, 1975, garnered “Wild World of Sports” highest viewer ratings in its history. Knievel again announced his retirement, and again later reneged.

He should have gone out on top. As it turned out, the 38-year-old’s career was about to jump the shark. Literally. Just months before the episode of “Happy Days” that featured Fonzie jumping a shark, Knievel also had it on his docket.

While preparing to clear 13 sharks in a 90-foot-long tank at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Knievel crashed on a practice run, breaking his collarbone and right arm. He would never jump again.

Busted Down And Busted

Knievel’s life began a rapid downward spiral in 1977. His longtime friend and promoter Shelly Saltman wrote a book about the stuntman that made unflattering accusations. An irate Knievel, arm still in a cast, beat Silverman with a baseball bat on Sept. 21, 1977.

During the ensuing trial, Knievel fired his attorney, pleaded guilty and says, given the chance, he would do it again. He’s sentenced to six months in jail for felony assault, served nights and weekends.

Undaunted, Knievel uses his incarceration as a persona building opportunity. He hires a dozen limos to drive he and his fellow inmates to their jobs on a work-release program.

But the end is near. Ideal pulls Knievel toys and cancels all licensing with the aging star. Revenue streams dry up, the wheels come off and Knievel withdraws from the public eye as most of his assets are sold or repossessed.

Knievel makes a rare appearance in Twin Falls in 1985 to commemorate the 10-year anniversary of his Snake River debacle.

"This great old Snake River Canyon is still standing here. God has not moved it one single inch and that take off-ramp is still on the edge where we can see it, and I don't see no big long line of daredevils standing here wanting to jump across it," he said at the ceremony.

With his health in decline, Knievel would divorce Linda in 1997. He married Krystal Kennedy in 1999, only to divorce her in 2001. The couple would reconcile and Kennedy was with Knievel as he died on Nov. 30, 2007, at the age of 69 due to diabetes and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Knievel’s funeral was a grand affair. Thousands attended the sendoff in his hometown of Butte. Matthew McConaughey delivered a stirring eulogy.

Years later in 2017, one of Knievel’s Liberace-inspired star-spangled jumpsuits, complete with matching cape and boots, sold for more than $100,000.

Knievel’s son, Robbie, would go on to break every record his father set. He did so on a lighter, more powerful motorcycle. He wasn’t first to dare and he did not have the bravado of Evel. And he knew it.

Evel’s eldest, Kelly, added, “My dad jumped 275 times and it's not the 260 times he made it that made him famous. It's the 15 times he crashed."

“I was always good at the takeoff, bad at the landings,” Evel admitted. “But that’s what people wanted to see. No one wants to see me die, but they don't want to miss it if I do.”

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.