Your county fair wrapped up recently, wherever you are in Wyoming. Somewhere, a spirited youngster counts his or her money, socks it away in a college fund and is already planning how to improve next year’s feeding program.

Agriculture programs like 4-H and FFA have come to mean big bucks for participants while sowing the seed of real-life lessons for a generation hopelessly addicted to its electronics. For these kids, summer is for getting dirty.

Since when is a rabbit worth $1,000? How does a steer fetch more on the hoof than it sells for wrapped in cellophane at the butcher shop? There’s enough money in the Big Horn County pig pen to send a kid to MIT for a semester.

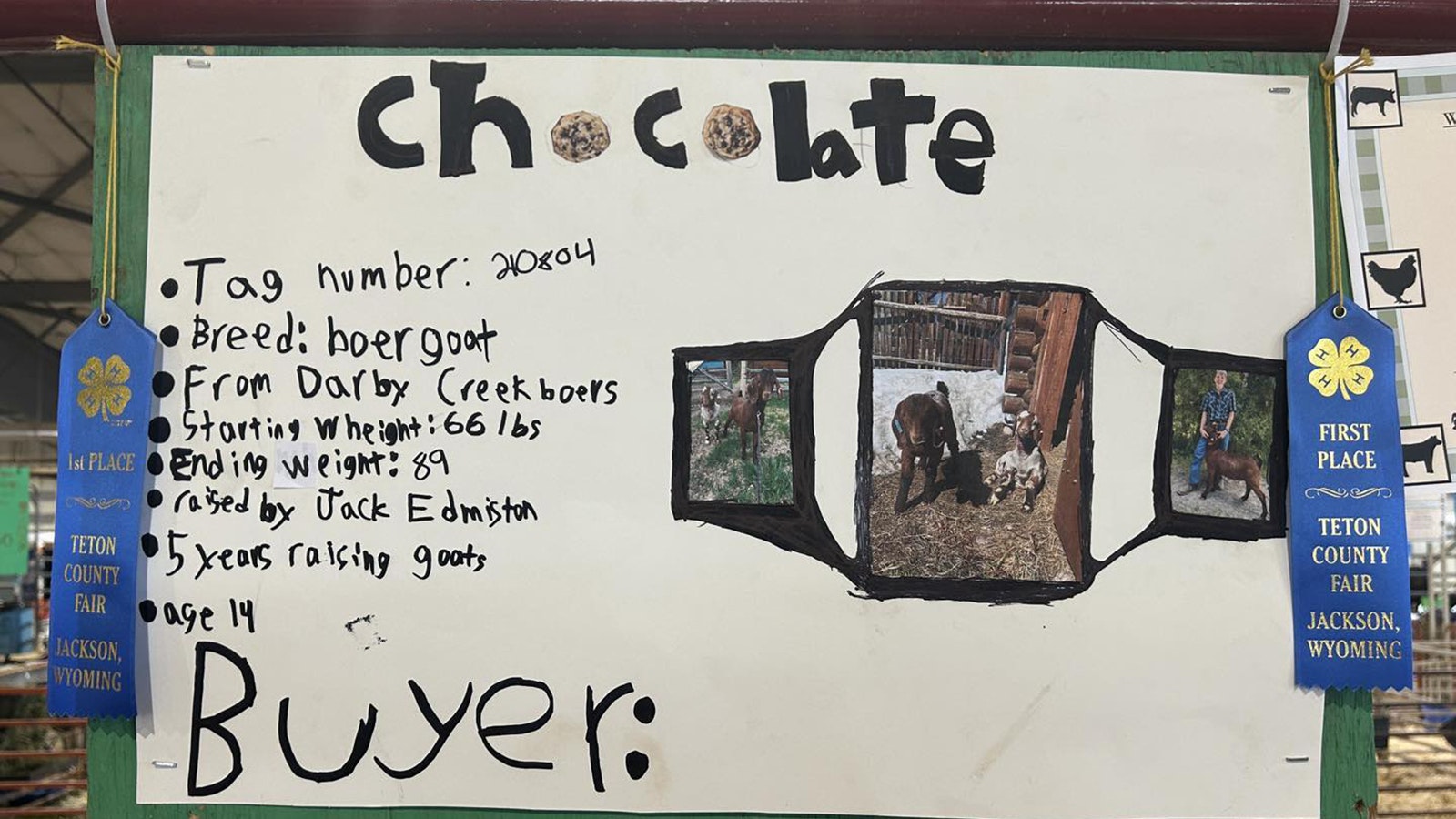

Junior stock growers in 4-H programs across Wyoming might not be getting an accurate picture of real-world economics, but they are without fail handsomely rewarded for their animal husbandry efforts at the county fair livestock auction.

Fair Market

Little Bo Peeps reap from their sheep. Beef is big bucks. And the 4-H program across the state is alive and well.

The barn sale at a fair’s junior livestock auction might not represent real-life conditions. Where else would a kindly grandmother, a local banker and reps from an area architecture firm all keep raising their paddles, happily outbidding each other for a scraggly goat, then tickled as can be when the auctioneer finally drops the hammer on an outrageous sum?

First, at the fair it's all about the animals in the show ring. Judges turn a trained eye to that grand champion steer with the shiny coat or that luscious lamb with impeccable conformation.

In the sale ring, it’s the kids’ turn to shine. Generational ranch families, that urban newbie just getting involved, and the hard luck case whose animal died of colic a month ago. There are a thousand reasons why someone in the crowd might spend thousands to buy a 4-H project.

Few ask why, and those with numbers pinned to their backs only want to know how much.

4-H For The Future

Ag programs like 4-H and Future Farmers of America continue to attract today’s youth into a world away from screens and into a hands-on experience with critical life skills.

4-H, for example, is the nation’s largest youth development organization with some 6 million kids ages 5-18 involved via a network of 100 public universities in the U.S., including University of Wyoming.

At the core of the program is animal husbandry, a branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, fiber, milk or other products. This controlled cultivation, management and production of domestic animals has been going on since man first erected a fence.

Today, breeding, raising and selling/slaughtering of livestock is practically a lost art in the big city. There is a huge disconnection between Bessie and Wilbur and the translation to milk and bacon, for example.

The whole concept of 4-H and FFA also have come under attack from PETA, which claims these programs teach kids to “harden their hearts.”

In Wyoming, a 4-H project culminates at the local county fair where certainly there are tears at the off-ramp. All that feeding, gentling and brushing inevitably forms a bond between kid and critter. They knew the endgame when they signed up. Still, younger ones take goodbyes the hardest.

Bye Bye Black Sheep

Thirteen-year-old Evi Courser has become the comforter of other kids on load-up day at the Teton County Fair. She remembers what it was like that first year in 2019.

“I wasn’t prepared that first year to let my lamb go. It’s like losing your first dog,” Courser said. “My second year, I had a lamb die from bloat and had to get another lamb but missed the deadline for fair. So I sold to a private buyer, which meant I had to load it and bring it to the butcher myself, and that made it especially hard.”

Courser got through it and learned valuable life lessons, she says. She shares that with younger participants now as a mentor and comforter on sale day. That, too, is part of the 4-H experience: building leaders.

Bente Somers, 15, admitted to “some tears” last fair when she sold her first lamb. But parting with Pork Chop this summer was not as rough. She was able to console a friend’s little sister with a knowing hug.

Twelve-year-old Isabelle Cox also started in 4-H last year and had an emotional goodbye scene with her lamb then.

“Super upset,” is how she described it.

This year, not so much when Biggie Smalls was loaded onto the trailer that final day.

Maybe it’s harder for the girls. Preston Sandretto, 16, now in his sixth year of 4-H said the first couple years were difficult, but the past few he’s been “ready to get rid of it.”

Sandretto also has been playing mentor to some of the younger kids in the program.

“Definitely my first year there was a learning curve. Second year, I've been helping ever since then,” he said. “I am still learning stuff I didn’t know about. I have a lot to share and a lot to learn.”

Not All Lemonade And Skittles

Most every kid in 4-H cites an older sibling or a friend who got them involved.

Courser has an older sister who dabbled and a friend Gigi who needed a partner with her lamb. Cox and Sandretto have similar stories. Somers just went with the flow when it seemed everyone in the neighborhood was showing lambs.

The first thing many find out is what a responsibility it is to care for an animal. There’s a lot manure shoveling — like in real life — and fiduciary concerns as well.

“Every year you trust there is going to be income more than what you paid. This year, I had to pay my mom at least $700 for expenses. You are always learning about finances, what you are netting,” said Courser, who began showmanship in horses and dogs.

Courser, who began at age 9, plans to show every year until she ages out, which would put her in line for 4-H college scholarship money.

Somers had an easy break-in period last year when her grandmother, who was also involved in 4-H in her childhood, gifted her a lamb.

“She said, ‘Let me buy your lamb for you so you are not starting at minus $500.’ Without that original expense it was mainly buckets, feed bins, grain and hay that I had to cover,” Somers said.

Called Up To The Show

The financial aspect culminates with a fair’s livestock auction. Long before that day, 4-H kids compose and send letters to prospective buyers and have a “thank you” basket ready to go to the highest bidder on sale day.

“I wrote a lot of buyers letters. Told them about myself and all the hard work and costs that go into raising a lamb,” Somers said. “I hand-delivered most of them because I think that face-to-face is the most effective way to sell yourself.”

Things do go wrong long before fair week, which can be intense, to say the least.

Courser’s Calambity Jane proved to be an escape artist. Of course, a mutton on the lam is a lot easier when gates are left unlatched.

“Our lambs would get out of the pen almost every day. We weren’t very good about closing the gate,” Courser said. “It’s stressful during the fair, but we could laugh about it after.”

Last year, Somers’ lamb jumped a fence to get at some good grass. This year, Pork Chop had the entire 4-H barn chasing her with ropes after a brief escape from its pen.

Cox simply had her lamb run her right over once.

“A bunch of us would meet at a friend’s house where we kept our lambs at a set time every day to walk them,” Cox said. “I lived the furthest away and usually ended up being a little late so my partners would start without me.

“This one time, they were probably 100 feet down the road already when I opened the gate to get my lamb who had crazy separation anxiety. I opened the gate and she full on threw herself at me and knocked me over. From that day forward my partners never left the pen without me.”

Cash Cow

Relative to their respective size, just about every 4-H county fair livestock sale was up in 2023. COVID not only failed to stop or slow the 4-H livestock programs, in many places it boosted it.

Joe Bridges says the Park County Fair was one of the quickest to respond to the pandemic.

“We saw a big jump in prices about three years ago. We went online with our auction right out of the gate when COVID hit and survived it pretty good,” Bridges said. “We’ve since dropped that because people want to be there now but the numbers have stayed strong.”

Rabbits were big this year in Park County.

Most years, about 10 will show. This year, 33 were entered, and the highest selling rabbit went for $1,500.

Goats were also strong, a trend that began six or seven years ago when Bridges noticed a lot of kids leaving the lamb barn for the goat barn.

Record Numbers

Park County saw $632,028 in total animal sales.

A record-breaking trend is underway at the Albany County Fair where $843,320 was the grand total in 2023, easily topping last year’s $790,335.

Entries were also up across the board, according to fairgrounds director Taylor Haley.

At the Big Horn County Fair, 4-H sales also are trending upward.

Casey Sorenson at the Bank of Greybull keeps the records for the livestock auction. He said the sale did $274,083 this year, up slightly over 2022’s $270,773, but with 17 fewer animals on the auction block. In 2021, the Big Horn County Fair did $244,059, $237,646 in 2020.

“The community showed up, as always, to support our youth,” Sorenson said. “The sale started out slow, but about halfway through, the prices started to increase and sustain through the remainder of the sale.

“We had some new buyers, buyers outside of the county, but most of the support has come from the same buyers that have supported the fair and our youth for decades.”

In Johnson and Teton counties, numbers were down slightly in 2023, but only because they were astronomically high during the pandemic years.

Teton pulled in $739,000 this year with 119 animal lots going through. That could not keep pace with last year’s record-breaking $859,000, but it wasn’t exactly chump change, said 4-H leader Glenn Owings.

“We have such tremendously generous buyers,” Owings said, adding that somewhere between 30% and 50% of the animals bought at auction are donated back to charitable nonprofits in the community.

Livestock committee chair Keefer Rice said the Johnson County fat stock auction was a little off this year compared to 2022 when the final tally was around $625,000. This year’s take was about $550,000. That marks three straight years above the half million-dollar mark, which was breached in 2021 for the first time.

“Sheep remain king in Johnson County,” assured Rice, of the region’s longstanding heritage with the domestic species. Goats and rabbits were also up.

Swine did well also. Rice’s daughters — Katie, 15, and Emily, 12 — both showed pigs this year to enthusiastic buyers.

Now that the whirlwind of county fair time is in the rear-view mirror for Wyoming youth, they’re already focused on raising next year’s beef, swine, rabbit and other barnyard basics.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.