HULETT — North of Devils Tower in this tiny town is an unexpected adventure right on Main Street. The shop is called Rogue’s Gallery, owned by an unassuming artist and collector named Bob Coronato.

Coronato has made a name for himself with his Western art, much of it done right here in the Cowboy State. He’s the artist behind a number of iconic rodeo posters, and he’s also the guy who painted that life-size portrait of the late Russell Means, an Oglala Lakota activist for Native American rights, draped with an upside-down flag as a signal of distress.

That particular portrait has a permanent home in the Library of Congress. But an equally life-size print also hangs in the back room of RoguesGallery, along with a collection of Western artifacts Coronato has collected over 30 years from a number of Great Plains states.

The collection is part avocation and part livelihood that helps fund his art. But Coronato also has quite a soft spot in his heart for the West.

Lure Of The West

Coronato has always been fascinated by the West, from the earliest he can remember. When his parents mentioned they were taking a trip out West during his second year of college, Coronato had to join them.

During the trip, he saw an advertisement for paintings by Charles Russell at High Plains Heritage Museum in Spearfish, South Dakota. But when he went there, they had no paintings.

“So, I went to the curator and I said, ‘Hey, what happened?’”

Learning that the collection was being reorganized, Coronato made a bold move.

“I said, ‘Well, I do paintings. If you liked them, would you hang them up?’”

The curator agreed that he would indeed hang them up — if the paintings were good.

For the next two years, Coronato turned every college assignment into some kind of Western painting. It didn’t matter what the assignment was. Coronato was determined to make it Western. Automobiles became wagons with horses, and every person was a cowboy.

And it paid off.

The curator loved his paintings and had no problem hanging them up for a show.

During the show, however, a saddle maker named Carson Thomas noticed some mistakes Coronato had made, and he made the young artist an unusual offer.

“You move out to Wyoming, and I’ll get you working on a ranch and rent you an art studio real cheap,” he told Coronato.

“So, I went back, and in about a month I got to thinking, ‘Man, if I’m going to do this for real, everything’s got to be authentic,’” Coronato said. “So, I called him up and said, ‘Hey, was that offer serious?’”

Next thing Coronato knew, he was headed West with everything he owned. At that time, that was an easel and a single $100 bill.

In the beginning, Coronato provided a lot of free labor on ranches and painted at night in his art studio.

“The museum and store just grew from that,” Coronato said. “We always had people coming in. And a good friend of mine at the time, he was another artist named Tom Waugh. He suggested we turn it into an art gallery.”

Finding Things Is Coronato’s Other Favorite Art Form

The museum collection followed not long after.

“I’ve had a knack, ever since I was a little kid, of finding things,” Coronato told Cowboy State Daily.

Usually, it starts with a subject area of interest. Like the time he found an original drawing by Charles Schreyvogel, one of the West’s top three artists. The other two top artists, according to Coronato, are Charlie Russell and Frederick Remington.

“I think I was like 12 years old, and I’d asked my dad, ‘Hey, can you drive me to an antique store?’” Coronato said.

While in the store, Coronato saw this pen and ink drawing that had a familiar signature on it.

“I stashed it away in the antique store because I didn’t have the $10 to buy it,” Coronato said. “When I went home, I looked in my book, and sure enough, (the signature) was a match. So, I went back and bought it. That was sort of the first big piece that I ever found.”

The drawing that he’d paid $10 for turned out to be worth about $10,000.

How To Spot The Fakes

Of course, it didn’t end with finding just one pen-and-ink drawing. Coronato kept finding things, and he kept learning new methods for authenticating historical items to ensure he wasn’t buying something fake.

In college, he even figured out that an Etruscan urn he was supposed to be restoring wasn’t actually the real thing.

He figured that out by going to museums and studying the real objects and comparing them to the one he was restoring. By doing that, he was finally able to discern that the figures on his object had been made using a Dremel tool, not the period correct tools of the time.

“People can’t tell what’s real and what’s fake,” Coronato said. “But over the years, I’ve learned how, forensically, to tell.”

When it comes to beads, for example, the colors of the beads themselves are a significant clue.

“There’s probably thousands of shades of red, and some of them date back, they’re family secrets that go back to the 1600s in Venice,” Coronato said.

The authentic colors are a shade all their own, Coronato said, but it’s not just about the colors.

“There’s about 20 things that have to add up,” he said. “Somebody could get old beads and make a new item to try to pass it off as old. But they might not get the pattern right. They might not get the thread or the materials right. So, all these things have to add up, and that’s one of the ways you can tell.”

Having that sharp eye for beadwork allowed Coronato to identify a singular beadwork item on eBay out of probably a thousand fake items. It was a woolen coat, cut with tails, and decorated with beads.

“I’ve been told that’s probably the greatest historical artifact of beadwork ever found,” Coronato told Cowboy State Daily. “That ended up going on a world tour. It went to Paris, the Met, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and then went to the Nelson Atkins and was published in a couple of books.”

Tomahawk That Killed Caspar Collins

The other highly significant item Coronato mentions finding is an engraved tomahawk that the experts he worked with believe could have belonged to a Lakotan warrior named Stranger Horse.

The tomahawk doubled as a pipe, with a handle made of ash, and was decorated with pink and green beads.

The engravings were on the blade, which is blacksmith-forged steel. They were made with a method called rocker or file engraving, where a chisel is used to make lines in the metal.

The lines on the tomahawk’s blade depict a horse figure with tracks, which symbolizes many successful raids against enemies. But it also includes the torso of a cavalry officer in the U.S. Army whose throat has been cut and his hands removed.

“It was Caspar Collins’ death,” Coronato said he was told by the experts who reviewed the blade. “His death was engraved on that tomahawk. And the warrior that had it ended up becoming the head chief of the Lakota.”

Coronato displayed the item in museum for a time, hoping to sell it to a Wyoming museum and keep it in the state.

But ultimately, he ended up selling it to a private collector.

Rare Gun Find

One of Coronado’s favorite finds, which is still in his museum, is a gun he believes belonged to a writer named Russell Sage.

Sage traveled the West from 1841 to 1844, writing several books and papers out of his adventures. Among these was the story of Hugh Glass, which was included in the book “Scenes in the Rocky Mountains,” published in 1846.

“Actual mountain men guns are uncannily, I mean, ungodly rare,” Coronato said.

More commonly, such guns will turn out to be fakes from a place like India and Africa, which were similarly tacked and wrapped and put to the same hard use as on the American frontier.

Coronato was initially skeptical the gun would turn out to be real, given how common fakes are.

“This friend of mine had bought the gun at an antique store and said he’d sell it to me for a couple hundred bucks more than he had paid for it and mail it to me,” Coronato said. “And I said, ‘Well, if it’s not real, I want to be able to mail it back, and I don’t want to argue with you.’”

The deal was struck, and as soon as Coronato received the gun in the mail, he went about authenticating it.

“I look at it and the tacks are period tacks, from the correct time period,” Coronado said. “The museum tag on it doesn’t say what it is, it just says St. Paul Minnesota, but the way it’s wrapped is correct for native use.”

The small brass piece on the gun with a Native American ledger drawing of a guy with a Missouri water axe and rifle also seems period correct.

The real kicker would be a maker’s mark on the gun, Coronato decided. So, he moved the brass forward a bit, where he saw a piece of paper peeking out from underneath it.

“So, I poke it out, and there’s writing on it in iron gall ink, which is period ink, and on both sides of the paper it says ‘Rufus B. Sage, St. Louis, 1844,’” he said.

Coronato, at that point, didn’t know who Rufus Sage was, but Google helped him figure that out quickly.

“He was mapping out Wyoming and Colorado with the Fremont Party, which is Kit Carson,” Coronato said.

The Tale Of ‘Old Straightener’

Less quickly, Coronato had the ink and paper tested to be sure they were period correct, and he compared images of the signature to ensure they matched Rufus Sage.

After seven years, Coronato eventually also tracked down one of Sage’s original books, “Perilous Adventures in the Rocky Mountains told by an Easterner,” where he tells more about the gun.

“I’m going through the book, and he starts talking about his gun, and he says he’s out in the Black Hills, and it was winter, they were starving to death,” Coronato said. “And he thought, ‘Well, I’m gonna have to shoot my horses, because they were starving.’ But if they shoot their horses, they’re going to die.”

So, Sage decided to try hunting one last time. And on that day, he sees a buffalo cow under a pine tree.

“He goes to load the gun and shoot it, but it doesn’t go off,” Coronato said. “Probably, the powder was damp or something. So, he put a new cap on it and, when he goes to shoot the gun, it goes off by itself. It kills the buffalo dead with one shot.”

Sage wrote in the book that he would never get rid of the gun and called it “Old Straightener” after that because it was the only gun he’d ever had that shot game on its own accord.

The Collecting Goes Ever On

The gun is just one of dozens of cool artifacts in the tiny museum in the gallery’s back room, which is free to view. Coronato isn’t sure what’s next for Rogues Gallery, which turned 30 this year.

“I’m running out of space,” he said. “I’m gonna have to expand.”

Coronato doesn’t let the thought linger long, though, before he has walked across the museum to show off yet another cool item.

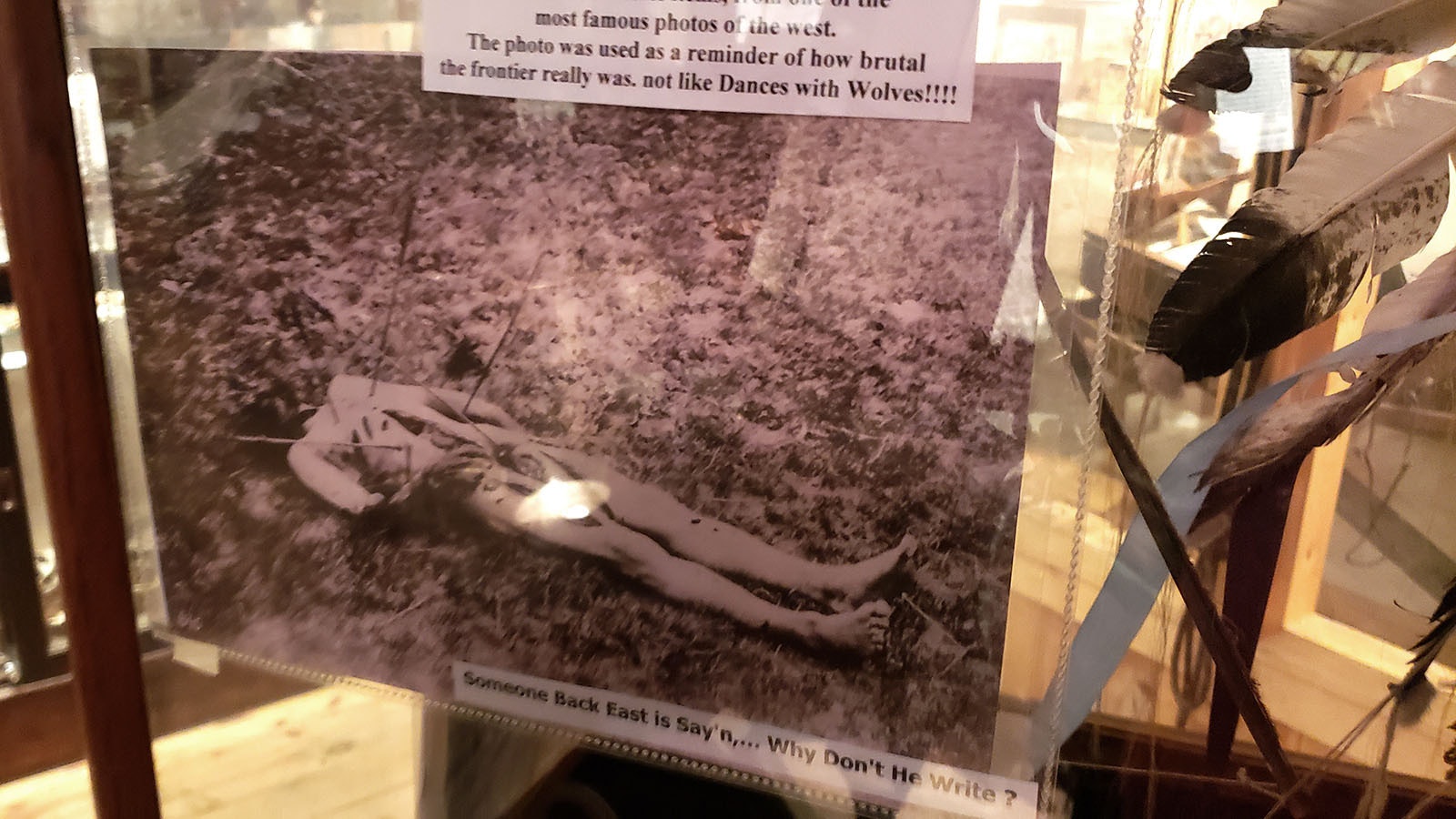

“This is a pretty rare item,” he says, pointing to an arrow, and then to a photo of a dead man with arrows sticking out of him like a pin cushion. “It’s an arrow that’s pulled out of that guy right there.”

On the arrow is a piece of museum paper that’s been glued to it that says the arrow was taken from the body of Sgt. Frederick Williams, 7th Cavalry, during an Indian attack.

“Part of it’s torn, so I can’t read it all,” he said. “But that’s a really famous photograph. He was left on the plains as a sign. And then a photographer actually took that photo to send to the president to show how bad it was out on the plains.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.