Game designers are producing board games to introduce players to the “effects of the climate crisis.”

In these games, players must eliminate fossil fuels and replace them with wind and solar farms. The players’ ability to avert global disaster and survive into the future depends on it.

While games are played for fun and entertainment, some are concerned about the extreme messages these kinds of materials about energy and the impacts of climate change are conveying, especially to kids.

Lyndsey Skatberg, a Sheridan mom who has worked in the oil and gas industry, is concerned about the messaging that’s reaching kids about the industry through media — and now games.

“We need to teach our kids where electricity comes from, not just the wall,” Scatberg told Cowboy State Daily.

Win By Losing

Among the board games is one called “CO2: Second Chance.”

According to the game description, pollution has become so great that humanity realizes all energy demand must be met with “clean sources of energy.” United Nations grants give nations carbon emissions permits, and players trade these credits throughout the game.

“If pollution isn’t stopped, it’s game over for all of us,” the description states.

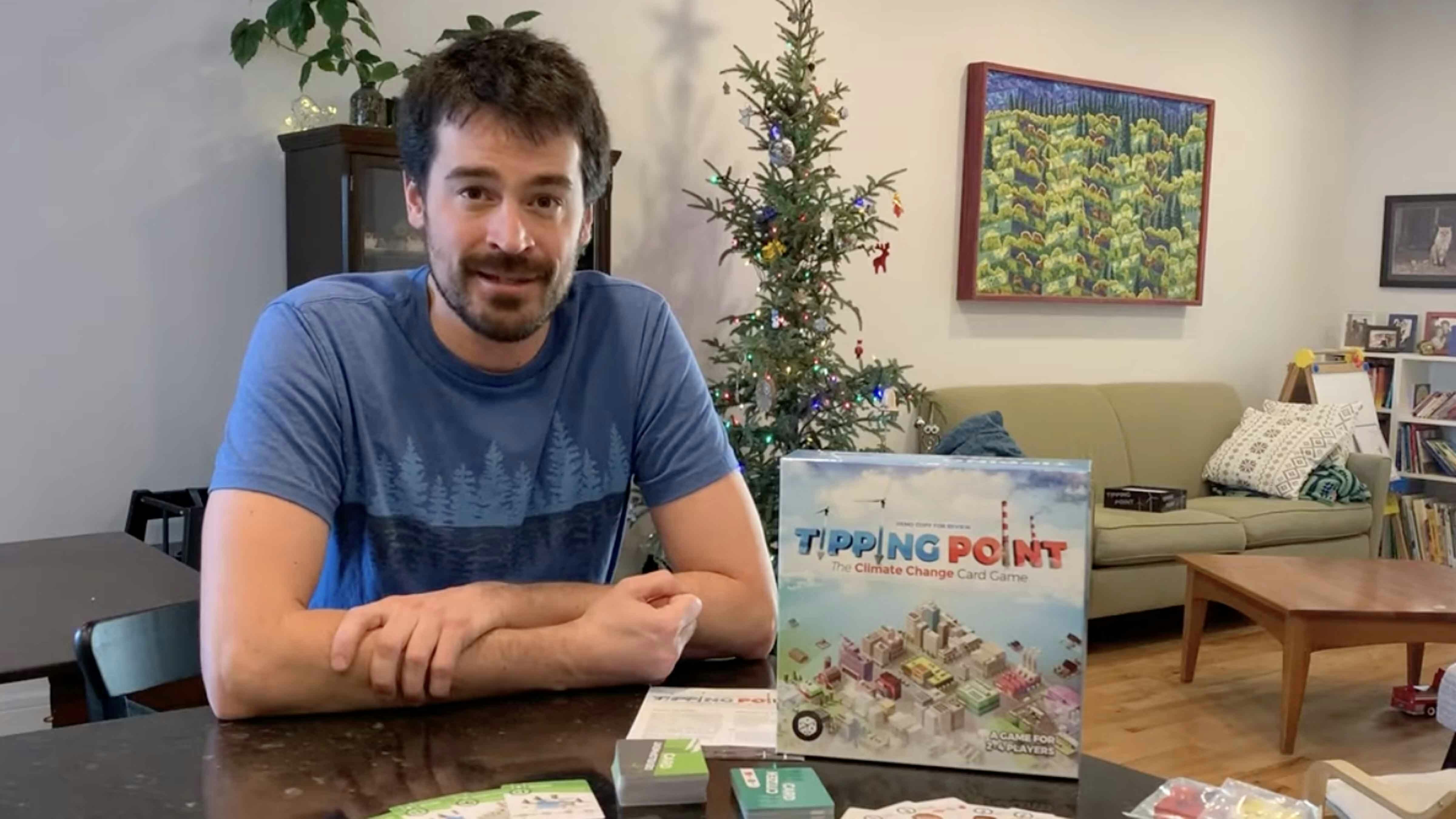

“Tipping Point” is a card game in which players try to reduce the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This greenhouse gas is leading to “ever more extreme weather disasters,” according to the game’s website.

The game creates a dichotomy where players can make fast cash by drilling for oil or take small steps to build a “green” economy with organic farming and solar panels.

Of course, no matter how prosperous the society you build becomes, if you don’t lower carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, you lose the game.

All Kinds Of Energy

J.P. Warren, co-founder of Connection Crüe, told Cowboy State Daily that these games have an obvious political agenda and a narrative they’re trying to communicate.

He said there’s nothing wrong with having a message in a game, but the problem with these overt board games is the lack of balance.

Connection Crüe, which Warren founded with his wife Monika, is a professional networking service for connecting industry leaders in the energy sector together.

“The idea is everyone is a teacher and everyone's a student. We all can learn something from someone else. So, it’s a collaboration,” Warren said.

Warren calls himself an energy advocate, and he’s had 18 years of experience in the oil and gas industry.

After starting Connection Crüe, the founders added Kids Crüe to promote STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) activities and careers to kids.

“We bring kids into learning about all kinds of energy,” Warren said.

One activity had kids drilling to extract chocolate milk as a demonstration of what petroleum production does.

Energy For Everyone

Warren wrote a children’s book titled “Energy For Everyone.”

The idea started when he heard a major figure at an oil company talking about how the number of college graduates in petroleum engineering has gone down over the past several years. Members of the audience were talking about how kids get such a negative view of fossil fuels from their education that they don’t view the petroleum industry as a potential career choice.

Warren wanted a book that gave kids a more balanced view of energy careers.

“I love all sorts of energy. However, let's be realistic about energy. All energy has pros and cons,” Warren said.

In the book, Trey and Evelyn, a character based on Warren's own daughter, are young, curious engineers who are always asking questions. The pair take a journey through the different types of energy and how they power the world.

“We need a balanced energy diet. You don't want to have ice cream for a week because that'll make your tummy hurt. You don't have broccoli for a week because that makes your tummy hurt as well,” Warren said.

Gloom And Doom

Besides the lack of balance in the messaging of the games is this gloom and doom scenario of the climate crisis, Warren said.

“I don’t think that makes a very fun game,” Warren said.

He said this crisis narrative is pervasive throughout the media, where everything is blamed on climate change.

“You talk about filling kids with anxiety,” Warren said.

He said there’s nothing wrong with educating kids on the impact carbon dioxide emissions have on climate, but the “climate crisis” narrative functions as buzzwords that seek a culprit to explain the source of all problems.

“I do think whenever you’re trying to teach your children with these gloom-and-doom scenarios, it takes away the art of growing up, thinking for yourself and understanding that issue from all sides,” Warren said.

Career Paths

The overall negative messaging about oil and gas may be why the number of graduates in petroleum engineering is down.

According to an annual survey of universities by Lloyd Heinze, a professor at Texas Tech University, the 25 schools that responded expect to award 679 bachelor of science degrees in petroleum engineering this year, down from 921 in 2022. In 2017, there were 2,615 graduates.

Astrid Northrup, professor of engineering and mathematics at Northwest College in Powell, told Cowboy State Daily that the boom-and-bust cycle of the industry also deters young people from pursuing petroleum engineering degrees. The jobs graduates get are among the highest paid of any field, but they end up working in all kinds of different environments all over the world as markets go up and down.

However, Northrup said, the degree also is a basis for other types of engineering.

“It’s a combination of chemistry, physics, geology, math and science,” Northrup said. “So, there's a lot of ancillary skills that engineers develop when they study petroleum engineering.”

What Petroleum Does

Northrup said the program at Northwest College gives students a two-year foundation for the four-year petroleum engineering degree. As tuition rates continue to climb, NWC provides students a more affordable option.

She said the students entering the program don’t have that negative attitude and understand that fossil fuels have a future.

“We don't want people to starve to death, and we don't want them to freeze to death,” Northrup said. “We still want them to have the opportunity for the population to have a middle class, healthy life. And that’s what petroleum does.”