SOUTH PASS CITY — Four masked riders came at a gallop on their horses, down from a hillside at the back of town, straight onto the Main Street of South Pass City.

The bandits fired their pistols into the air the moment their horse’s hooves hit Main Street. Firing the guns didn’t spook the horses, nor slow the riders at all. Smoke trailed out behind them as they came, shooting their way right up to the mercantile store.

As they hopped off their horses, pistols pointing around a circle of people in a gathered crowd, they advised the onlookers to stay well back and do nothing at all. That way, no one would be hurt.

Inside the mercantile, the bandits demanded all the cash on hand and advised the terrified merchant to wait inside the store for at least 30 minutes — or risk being shot to death.

The merchant readily agreed to wait, and the robbers left town the same way they had come in, shooting their guns on horses who appeared used to the sound.

Smoke marked the trail of the bandits but briefly. The wind soon carried away all trace, and the town eagerly returned to business as usual.

The moment took place during the recent Gold Rush Days at South Pass City, an annual two-day event celebrating the rough and tumble excitement of Wyoming’s most famous — or perhaps infamous — gold-rush town.

Pop-Up City

South Pass City sprang up almost overnight in 1868, after a detachment of Fort Bridger soldiers stumbled across nuggets of gold in the territory.

The soldiers had found indications of gold in the area while chasing horse thieves from Utah in the mid 1860s. They left the horse thieves to whatever fate might have in store for them when it became clear there were too many Indians in the area for safety.

They turned instead to the creeks in the area on a different kind of chase, a scouting mission panning to see what they might find.

Gold had long been rumored in the area, and a few soldiers liked what they saw enough to declare they would be back soon, once the Indians had left, to make a more extensive study.

It was on one of these later trips that the men found a quartz vein that had busted open, spilling sizable gold nuggets onto the ground. This find would later become known as the “Cariso Lode,” and it was the very first claim in what records called the newly formed “Shoshonie Mining District,” although the spelling is more usually Shoshone these days.

By the end of the spring of 1868, the H.S. Reedall party, which included some of the Fort Bridger soldiers had recovered $15,000 in gold between them — $750,000 in today’s money.

The Wyoming gold rush was on.

The Rush

South Pass was well-known as an important waypoint on the Oregon trail, but travelers did not generally wish to stay there for any length of time.

Gold in the hills changed that in short order.

The 1868 gold rush would bring between 3,000 to 5,000 people to the newly formed South Pass City at peak, according to James L. Sherlock’s account, “South Pass City And Its Tales.”

Similar numbers filled surrounding towns like Atlantic City, Sherlock wrote, bringing around 12,000 people to the area, most of them young men of about 28 years of age, actively seeking gold.

“South Pass City sprang up as fast as they could make lumber to make buildings,” Friends of South Pass City member and volunteer Greg Hester said. “That spring, there were thousands of people in these hills, all prospecting (for gold).”

Friends of South Pass City is dedicated to preserving South Pass City and educating people about its history.

By July 1869, three mills were turning and churning the quartz rock that’s associated with gold. Between them, there were a total of 26 stamps that could crush ore. There were also several “arrastres,” a Spanish word that means drag. The arrestre is a a basin built of stone or brick. A timber in the center turned spokes that dangled heavy granite rocks in the basin, to crush rock and separate out gold ore.

As quickly as South Pass City boomed, however, it went bust. By 1870, most prospectors had abandoned it, in their search for pastures more golden than those of South Pass.

By 1880, the census reported fewer than 200 people in the area, most of them ranchers and sheepherders — though a few miners did remain.

Gold Shines On

The allure of gold, however, is a strong one, and it would attract new investors to South Pass from time to time.

Among them was Bolivar Roberts, the brother of Homer Roberts, who was one of the original claimants of the Cariso Lode. Bolivar acquired the Carissa claim, as well as adjoining claims, forming the Carissa Gold Mining Company in 1885.

Historical records suggest Bolivar extracted $1 million dollars in gold from the Carissa before leasing it out to local miners, according to Susan Layman’s “History of Wyoming’s Carissa Gold Mine.”

In 1896, Chicago lumberman John C. Spry bought a controlling stake in the Carissa Gold Mining Company and subsequently formed the Federal Gold Mining Company. Spry bought up several adjacent claims as well, expanding the Carissa to its present-day size.

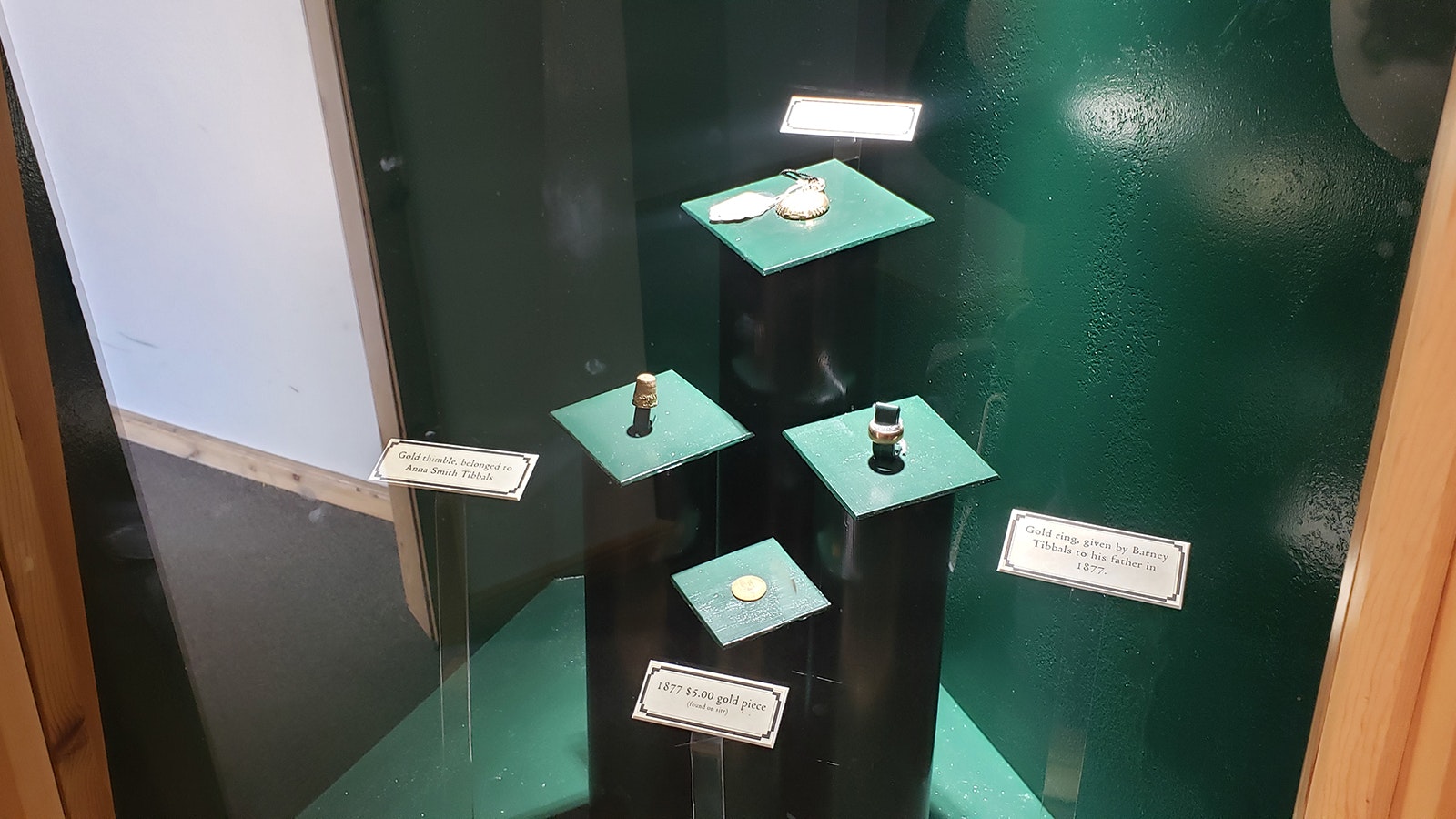

Working with experienced mining veteran, Barney N. Tibbals, the depth of the Carissa would reach four hundred feet, with five drift levels, which refers to a system of tunnels to get at the ore. Tibbals also had the men make numerous crosscuts to better define the body of ore.

Thirty men worked in the Carissa according to Federal Gold Mining Company records. They were miners, teamsters, wood cutters, and more.

Spry added a new mill by spring 1898, and was producing ore by that fall. The operation included cutting edge technology for the day. It was a 10-stamp mill with a Frue Vanner, a type of conveyor belt invented specifically for separating ore, and a Wilfley table, a vibrating series of wooden tabs invented to further separate ore. There was also an 18-inch bullion furnace to cast gold bars.

Denver mint records show at least 4,092.24 ounces of gold came out of the mine, worth a gross of $84,586.60. That’s about $6 million in modern coin.

Mint receipts for 1899, meanwhile, show 1,893.2 ounces, worth about $3 million in today’s money. Expenses for 1899, meanwhile, were $37,743.65, most of it payroll.

Laborers at the Carissa made $3 for a nine-hour day, while the foreman made $5.

Not A Vanderbilt

Despite turning a profit of over $2 million in 1899, Spry, was not satisfied with the mine’s productivity — as his frequent letters to Tibbals show.

Under Tibbals’ leadership, miners at the Federal Gold Mining Company were making a modest living, while Spry was receiving a reasonable profit from his investment.

But Spry didn’t want reasonable. He wanted to be a “Vanderbilt,” he told Tibbals in one of his many letters complaining that the mine wasn’t making enough money.

Spry shut the mines down in 1906, deciding he would sell the venture. But, his efforts to sell were hampered by a clause in the contract stating that Tibbals was to get $17,500 upon its sale. Spry actually let an option on the sale of the mine expire, whether to deny Tibbals the money he would have been owed, or because he couldn’t let go of the hope the mine would prove profitable one day.

Legal troubles related to the mine lived on after Spry’s death. Tibbals’ attorney, J.J. Spriggs filed a lien against Spry’s estate.

Spriggs would end up pursuing the case for the next 30 years or so, even after Tibbals had died. Spriggs kept on until his own eventual death.

The mine was nonetheless leased from time to time during this period, though it would never again reach the production levels — or the profitability — it had achieved under Tibbals.

Pure Tourism Gold

South Pass City was purchased by the state of Wyoming in 1967 and a restoration of the town has been ongoing ever since. Buildings that were giving way to weather and wind have been restored as artifacts in and of themselves.

Friends of South Pass City has played a big role in that effort, helping to raise funds each year to restore a new part of the city, or add something new and cool to it. A big part of that effort is the annual Gold Rush Days event, which invites people to come experience the town every year in July.

Thanks to these kinds of efforts, each of the remaining buildings in South Pass has been outfitted with period items that realistically show life as it was there at the turn of the century, when the surrounding hills were alive with men’s fevered dreams of gold.

Wyoming purchased the Carissa Mine in 2003, and it has since been restored to its 1929 appearance. Much of the equipment in the mine is still operational, and it is demonstrated during tours.

The site is open from June through Labor Day each year. Thousands will drop in to try their luck panning for actual gold in Willow Creek, before exploring the town or touring the Old English tunnel and the Carissa Mine.

During the recent Gold Rush day, hundreds lined either side of the creek, a pan of pay dirt in hand, to try their luck at spotting actual gold.

A literal ton of the pay dirt was brought in from Oregon Buttes, which is one of the many claims in the area.

Panning is simple enough for even young children to try. The pan is simply shaken a bit so that denser materials, like gold, will sink to the bottom, while less dense materials float upward and are washed away. Eventually, what remains in the pan can be inspected for valuables. A sparkling piece of garnet or, if one is lucky, gleaming flakes of gold.

These treasures may be placed in a small glass tube, provided with the pan of dirt, and kept as a souvenir of a one-of-a-kind experience in a famous gold rush city.

If You Go

South Pass City, Wyoming’s most famous gold-rush city, is open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Sunday beginning in June and lasting through Labor Day each year. The general admission fee is $8 for adults from out of state, and $4 for Wyoming residents. Kids 17 and under are free.

Tours of the mine and the Old English tunnel are available.

Visit online for details of events and tours.

South Pass City lies at more than 7,500 feet of elevation. Bring good walking shoes, plenty of water and sunblock for this day trip, which includes a couple of different hiking options.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.