SUNRISE — What used to be a lonely ghost town littered with vacant buildings and 225 acres of lost dreams is that no more.

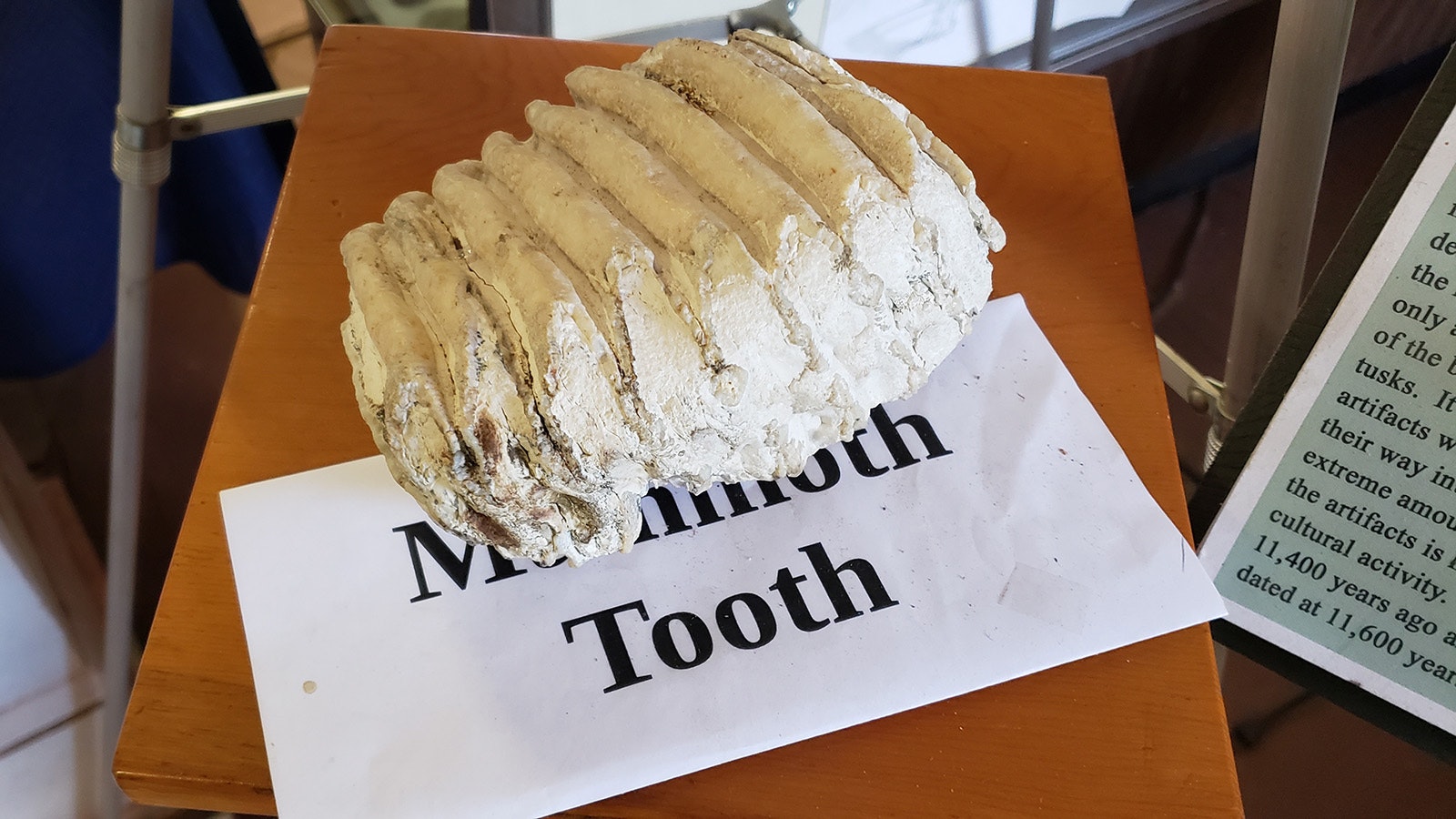

A new era is dawning for the mining town of Sunrise, Wyoming, at a site that offers a unique tourism opportunity. Not only have researchers found 14,000-year-old Paleoindian artifacts — the oldest in Wyoming if the finds prove out — but the site that is home to one of North America’s oldest red ochre mines can also offer a rich, historical picture of a company mining town.

John Voight purchased Sunrise in 2011 with visions dancing in his head of mining out the abandoned iron ore. The site where Colorado Fuel and Iron once held sway, and later John D. Rockefeller Sr. and then Jr., still had 20 years of ore left to mine when the Sunrise operation shut down in the early 1980s, a victim of changing tax laws that suddenly made it appear bankrupt.

Chinese Almost Owned Sunrise

Voight had met the former owner of Sunrise in Cheyenne and recalls accompanying him to tour the site, along with a group of Chinese investors whose plan was to move all the iron ore offshore within a two- to three-year period.

The owner confided to Voight he was troubled by the plan, and didn’t really want to sell the site to the Chinese.

Voight jumped at the chance to snap up the site instead, and today is glad he did, even though the mining aspect of his plan ran into some logistical problems that he cannot yet solve.

He sees long-term potential for the site to become something special in southeast Wyoming, where there is a confluence of history, heritage, and Paleoindian archaeology coming together, all in one site.

Paleoindians were the first people to live in the Americas after the final glacial episodes in the late Pleistocene. Powars II, which is located in Sunrise, has some of the oldest artifacts from that period in Wyoming, and the discoveries there are just getting started.

The Chinese wouldn’t have cared about any of that, Voight told a tour group riding along on his tractor for a tour on Saturday at the Powars II site.

Voight, meanwhile, is working to reclaim the brick buildings, replacing roofs that have finally given way to weather. He’s converting the brick homes that served as homes for Surnise mining bosses into AirBnBs for tourism at the site, as well as visiting scientists who are interested in the site’s geology, archaeology and even in its bats.

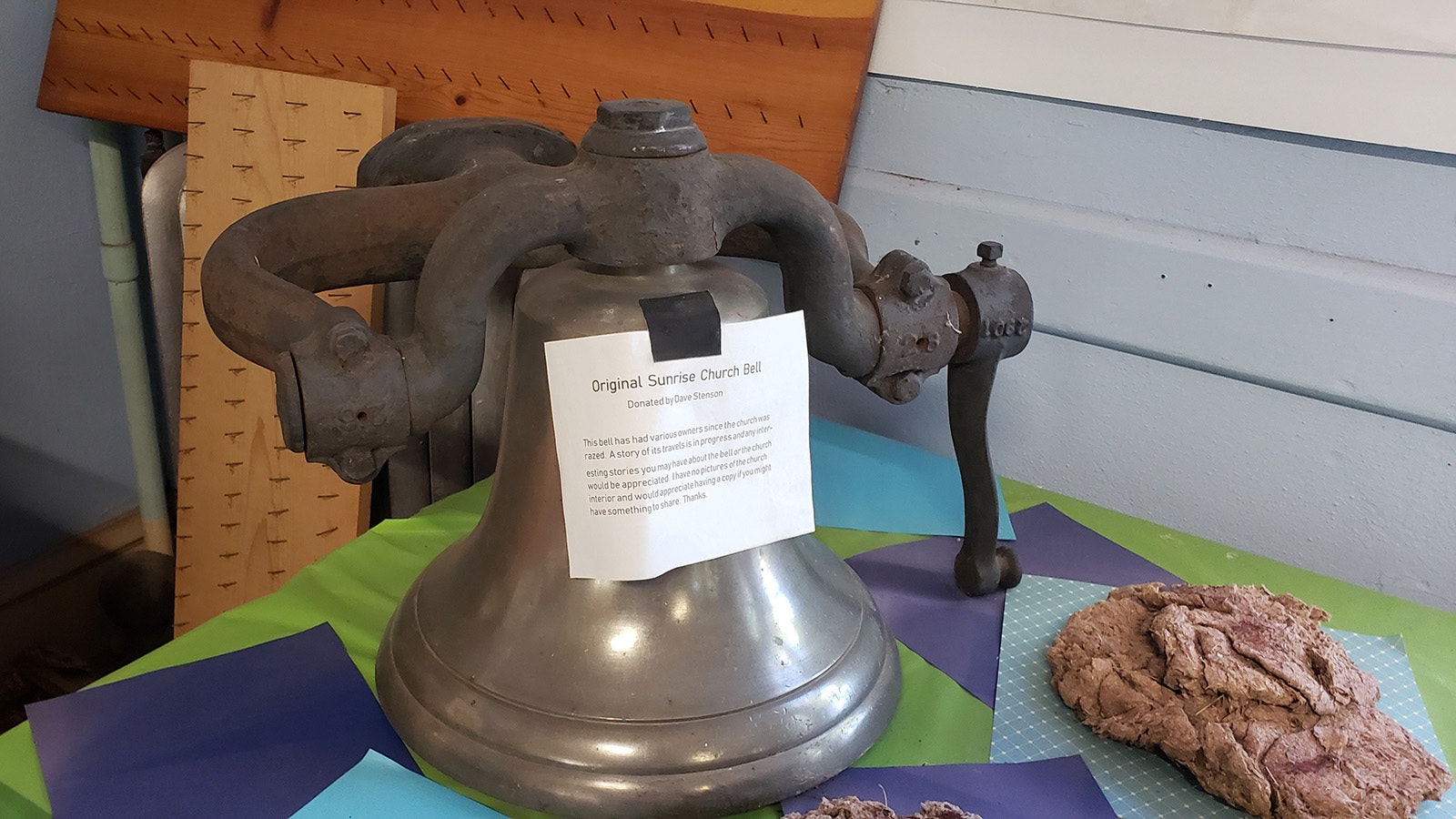

Voight has donated the YMCA to the Sunrise Historic and Prehistoric Preservation Society, which is setting up an interpretive museum to house artifacts from the site, whether Paleoindian, mining, or otherwise.

Many items, including artifacts discovered and catalogued by Dr. George Carr Frison, are already on display. Frison was Wyoming’s first state archaeologist, and worked at the Powars II site right up until his death in 2020.

Almost Destroyed By Wyoming

Nearly selling Sunrise, Wyoming to the Chinese is not the only time the Powars II site survived almost certain destruction. After the mining site was abandoned in 1984, the state of Wyoming was eventually ordered by a judge to take the site over and reclaim it.

The state’s mission at the time wasn’t to find a new buyer, or explore what cultural resources might exist at the site. It’s court-appointed charge was to return the site to the condition it had been in before mining began.

But, an artifact hunter whose last name was Powars, understood the importance of the site. He’d discovered some Paleoindian artifacts there back in the 30s and 40s, but had left the area after World War II. When he came for a 1986 reunion, though, he’d planned to revisit the site.

“He was planning to do a little more collecting of artifacts,” former state archaeologist George Zeimans told a crowd of Sunrise and Powars II supporters who gathered to tour the mining town and archaeological site on Saturday.

But, at the same time as Powars’ visit, the state of Wyoming was in the midst of its court-ordered reclamation work on the hillside.

“He got here on Sunday, after they’d come across with dozers and had reclaimed that site right up to its edge,” Zeimans said, pointing to a tarp-covered trench where artifacts have been found at one of North America’s oldest red ochre mines.

“Luckily, Mr. Powars came up here Sunday and saw what was going on,” Zeimans said.

Powars placed a call to a friend he had at the Smithsonian, who in turn called Frison.

“They were able to stop the reclamation,” Zeimans said. “Monday morning, they would have gone across and completely destroyed this site. In reality, we came within one day of losing the site.”

Another Thing That Makes Sunrise So Unusual

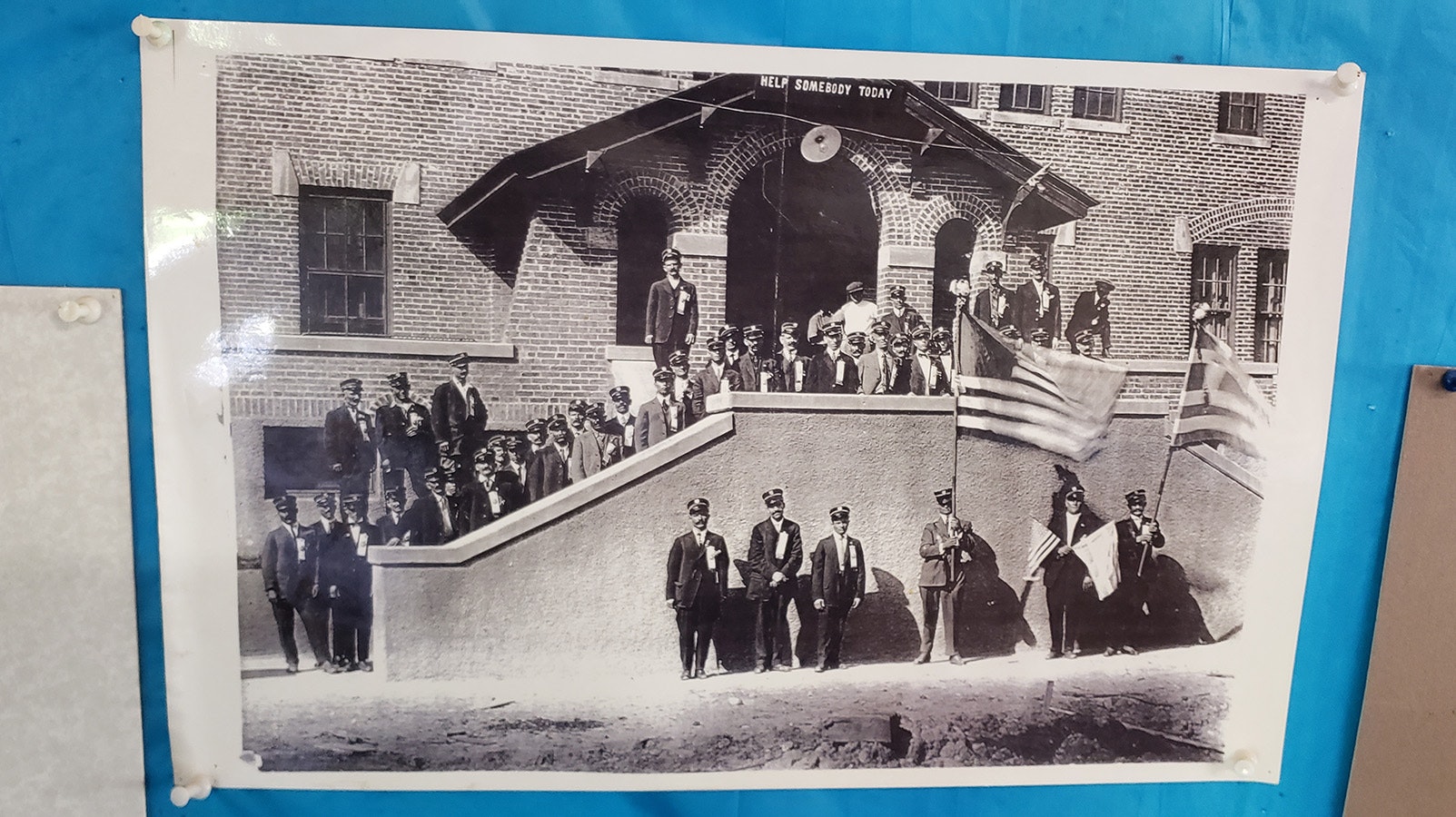

Intact company mining towns like Sunrise are unusual.

For one, mining companies take out bonds promising to level a site and return it to its former condition. That would have meant destroying the existing buildings on site — even the brick ones — razing them to the ground.

But, since the company abandoned the site and forfeited its bond in the early 1980s, all of the brick buildings that Rockefeller Jr. built on the site as part of his efforts to improve conditions there have been left to stand the test of time.

They have stood it well, too, showing little signs of the passing decades. They look to the casual observer as if they could have been built within the past 20 or 30 years, instead of being actually more than 100 years old.

The YMCA that Rockefeller built is particularly grand. It served as a community-wide center with a three-lane bowling alley in its basement and a theater upstairs. It included a cafeteria that served meals and snacks. Former residents recall it had one of the only televisions in the area at the time, and it served as an oasis of civilization in a community that had to be almost totally self-sufficient.

Growing Up Sunrise

Sunrise, Wyoming had no mayor at the time. Instead, it had a superintendent, who played much the same role.

Sunrise also had night watchmen, former resident Ray Monsoldo recalled. As a boy, growing up, he and his friends knew all about the night watchmen and their schedules — the better to avoid getting into trouble. Though, Monsoldo admitted, they did get in trouble a “time or two.”

Growing up in the company mining town was a one-of-a-kind experience, Monsoldo and Kathy Troupe said.

“That TV snowed all the time,” Monsoldo joked. “It must have been winter. But we’d go there often to watch television with peanuts and pop.”

Children would be given a whole nickel if they’d consent to run messages from the YMCA to residences in Sunrise, he added, and the building hosted safety meetings and Boy Scout meetings alike.

“It was the best place to grow up as a kid,” he said. “The YMCA had a three-lane bowling alley, and it had hot showers. We played up in these hills and our folks could turn us loose. We did our own thing.”

Troupe recalled how her father was one of the last miners on the site, working as part of the crew that was clearing the mine out to shut it down.

“The last day was in 1983,” she said. “And he didn’t want to leave. He loved it here.”

Bosses got the brick houses, Troupe said. But even the superintendent didn’t own his own house.

“They’d give you paint (for the houses), and they took care of you,” she said. “Which was kind of not a good thing in some ways, as we now know.”

Average wages were $1.95 to $2 a day, although blacksmiths could make more at $2.25 a day.

Only after unions came in did wages go up, Troupe said.

“My dad was making 89 cents an hour in the 1960s,” Troupe said.

But, after unions, Troupe recalls her dad making $8 an hour.

Monsoldo and Troupe are part of a group of supporters who have joined the Sunrise Historic and Prehistoric Preservation Society in hopes of preserving Sunrise for future generations to enjoy, part of a second life for what was once their home.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.