We’d simply ran out of options. Golden eagles and bald eagles were preying on newborn lambs in our lambing flock, and for the past few weeks we were finding at least one new eagle-killed lamb every day.

Both species of eagles are protected under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, with criminal penalties of up to $100,000 and imprisonment for up to a year for violations. The law is specific when it comes to prohibitions on “take” of an eagle, which means to “pursue, shoot, shoot at, poison, wound, kill, capture, trap, collect, molest or disturb."

We were already using livestock guardian dogs and were keeping the flock herded and concentrated as much as possible considering that the flock was giving birth to lambs on open range. The big dogs harassed the birds and tried to keep them away from the sheep, but the eagles were persistent.

We time our lambing season so that our ewes give birth at the same time as the pronghorn antelope that share the same range. But with the severe winter kill of wildlife herds, there just weren’t many wild fawns on the ground. It makes sense that eagles would turn to the most abundant food source available, which happens to be newborn lambs. Our lamb-a-day death loss is small compared to some of the neighboring sheep flocks that were getting hit much harder, with more eagles concentrating on their lambing ranges.

One afternoon I watched two newborn lambs stand and began to nurse on their mother before retreating to let them have this needed bonding time. When I returned a few hours later on my next check, I encountered a golden eagle walking on the ground toward the ewe, wings outstretched, trying to intimidate the ewe to flee from her lambs. But the ewe had backed her lambs into the tall brush behind her, and wasn’t having any of the eagle’s aggression, facing the eagle head on and stomping with her front hooves, refusing to budge. I chased the eagle away with the truck and then hurried to grab a dog out of the main flock and dropped her with the ewe and her lambs for protection.

We hazed the eagles by chasing them in the truck, and used a variety of noise-making techniques, while consulting with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service about what hazing activities were allowed. We consulted with animal damage control specialists, other sheep producers, eagle experts, and federal wildlife officials, and they all reported that effective options to deter eagles were very limited.

One option would be live trapping and relocating some of the eagles, but that would require a federal permit, which would take time and would require expert eagle handlers willing to spend time on the ranch to do the work. That may be a good option, but we were just two weeks from the end of the lambing season, so what we were looking for was a short-term fix. We found it in a scientific paper published 40 years ago. Ten years of eagle research on a Montana ranch examined a variety of deterrence techniques and offered up an old-school idea for the short term: scarecrows.

Scarecrows have been used all over the world for thousands of years to deter birds from grain fields, and as one researcher described, “Instantly recognizable, it is thought to be a premodern form of deception devised by the earliest pastoral peoples.”

Jim and I grabbed some supplies and headed out to install our first scarecrows on the edges of the lambing grounds. There’s not much to their construction: just a steel t-post with a short length of 2x4 tied near the top of the post to allow some wore out coveralls or clothes to be added, with a few branches of dead brush stuffed inside give the figure some bulk. I glued images of big eyeballs onto some old sunglasses, and added a hat onto a milk jug (turned upside down) to complete the look. By cutting a slit into the top of the jug, when turned upside down it fits snugly over the t-post. We secured everything with cotton twine or zipties.

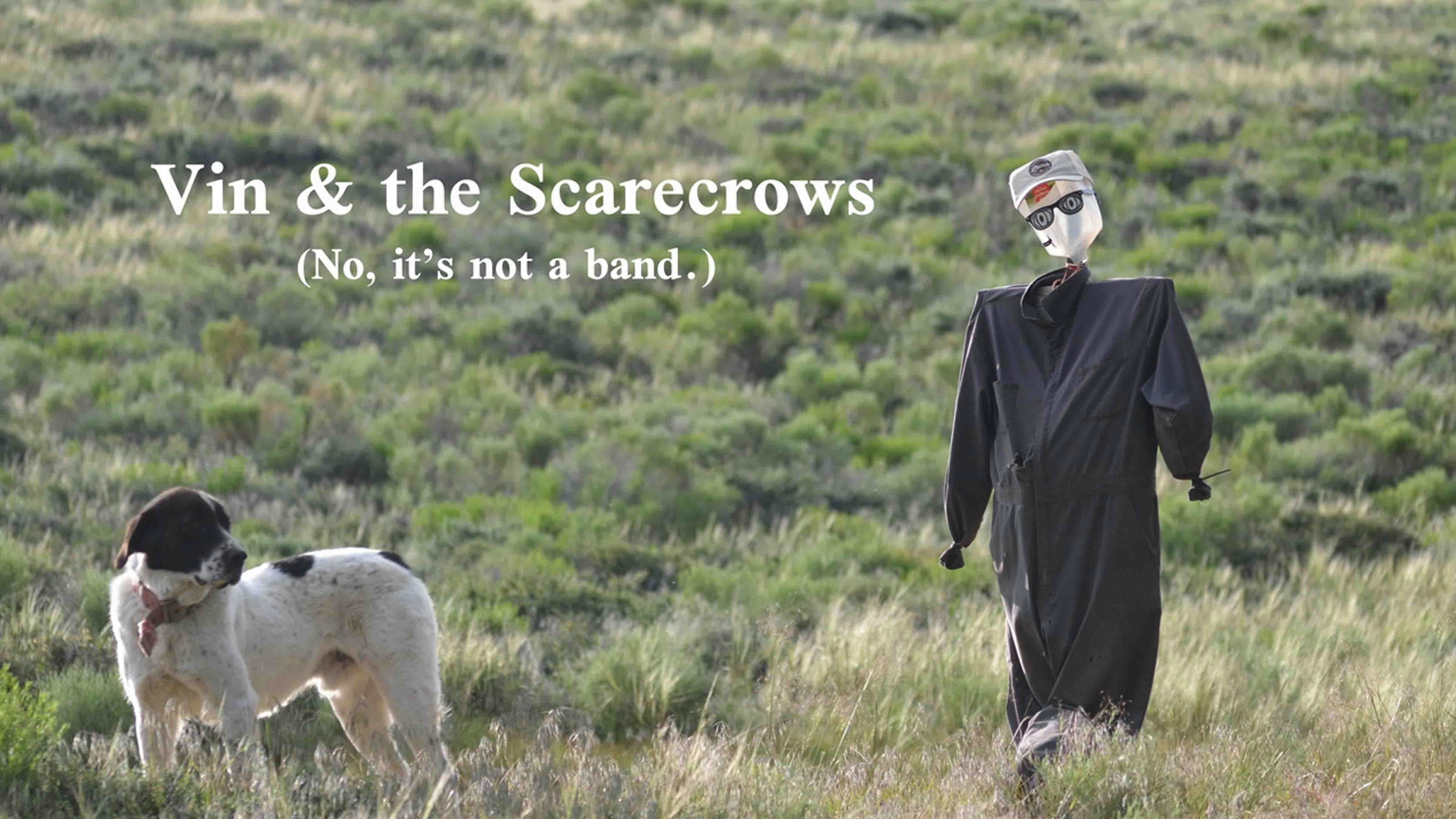

The scarecrows are lightweight enough that the arms and one leg shift positions in the wind. I was able to watch one of the guardian dogs, Panda, when he saw a scarecrow for the first time, and he was soon involved in a standoff with the strange-looking figure standing on the ditch bank above the flock. His alarm at the figure was a good indication of how the eagles would react. I laughed when our young herding dog, Fly, approached a second scarecrow with a wagging tail, apparently expecting to be petted by this figure wearing some of Jim’s old work clothes.

The ploy must have worked because we stopped finding eagle kills. For the first few days we saw eagles flying overhead, but they didn’t land. But by the fourth day, we had two golden eagles back to perching on ridge above the sheep and its scarecrows. By then the number of new lambs being born was dwindling, so we just needed to get by a little longer (so we hope).

Leave it to man’s best friend to provide the answer. One of the livestock guardian dogs, Vin, had been staying at our son’s place, but returned to the ranch and was alarmed when he encountered the scarecrows. He spent a day raising the alarm, but failed to get any of the other dogs to care by that time. Resigned to the situation, Vin has taken up residency on the ground next to the scarecrow. He’s been out there for two days. From a distance, it appears that a man and his dog are stationed along the ditch bank.

I have no idea what Vin is thinking; is he guarding the scarecrow from disturbance, or making sure the scarecrow doesn’t approach the sheep? Regardless, the addition of the dog next to the scarecrow has provided enough change in their environment that the eagles are once again keeping their distance.

Vin will eventually tire of his solitary sentry and go back to patrolling with the other dogs as they move with the sheep. When that happens, we’ll add some colored streamers and piepans to the scarecrows to change their appearance. Soon we’ll be able to dismantle the scarecrows as the lambing season concludes.

Next year, we’ll be ready for the eagles with new scarecrows, but it’s up to Vin whether they’ll be convincing enough for a repeat performance.

Cat Urbigkit is an author and rancher who lives on the range in Sublette County, Wyoming. Her column, Range Writing, appears weekly in Cowboy State Daily.