Harvey Morgan didn’t know trying to visit a widow would turn him into a ghoulish artifact, but history doesn’t recognize when it’s forming.

Morgan drove a wagon from South Pass City on a sighing June day 153 years ago to meet with the widow Schaeffer for business, or romance, or both. Mrs. Schaeffer’s husband had just died. She lived alone on a modest farm in a valley about 38 miles from South Pass City.

Two men accompanied Morgan on the road from town, Doc Barr and Jerome Mason. They all set out for a valley of sagebrush and sparse farms near the U.S. Army’s Camp Brown. The region would later incorporate under the name Lander, though early locals called it Pushroot.

“There were two stories,” Todd Guenther, Wyoming anthropology expert and retired history professor, told Cowboy State Daily. “One is, he was going down there because he was courting her. Another is, he was going down to visit her because he was going to buy that farm.”

At 25 years old Morgan was a jack-of-all-trades, a business owner, and an enterpriser. He had plans to open a saloon in downtown South Pass City. And he was popular. The local newspaper tracked his comings and goings from the nearest commerce hub, Salt Lake City.

“That was part of the news of the day,” said Guenther. “Now it’s considered an invasion of privacy.”

Numerous news stories tracked Morgan’s activities. Everyone spoke highly of him, Guenther said.

Barr and Mason may have been involved in the ranch deal, if there was one, or they may have had business of their own in the valley.

It was June 27, 1870 – one of the finest dates Wyoming has to offer, weather-wise. None of the three men survived it.

Don’t Go Down There

Other prospectors were too spooked to go down the hill that day. Either they’d seen the large roving war party of about 200 American Indians, or they’d seen the tracks. They urged Morgan’s party not to go.

“Don’t go down there, there’s too many Indians out there,” recounted Guenther from the stories.

A narrative posted above Morgan’s skull in the Pioneer Museum gives a different account. It says Morgan’s group encountered Major L.W. Kuykendall and his men. The soldiers had just been flanked by the Indian band but weren’t attacked because they were hauling cannons and packing guns, says the museum’s account.

Either way, Morgan and his companions insisted on driving the wagon down anyway, past what is now known as Dead Man’s Gulch.

The gulch isn’t named for Morgan’s party but for a murder victim found there several years later, said Guenther.

Your Final Adornment

The native war band attacked the three men.

Morgan and the others fought back with one faulty rifle, according to Guenther’s sources.

The band cinched around them. The three defenders threw the wagon box off its running gear, crouched under it and fired the occasional shot through a seam of light. They only had a handful of bullets.

They were overrun, killed, mutilated and butchered.

The Indians’ ritual mutilation wasn’t some dark indulgence as portrayed in old Westerns, said Guenther. It was a religious custom.

“Their beliefs were that after you killed an enemy, you mutilated their body (so that) if you met them again in the next life they’d still have those wounds and wouldn’t be able to hurt you,” he said.

Morgan’s killers found his wagon hammer, a multipurpose tool for hammering things and hitching the wagon’s body to its yoke. The hammer, or “queen pin” had a spike on one end and a hammer head on the other.

It would fit perfectly in a warrior’s hand, with its spike protruding from between his clenched fingers.

The hammer remains in Morgan’s skull 153 years later. It’s his defining adornment.

Sharp divots along the bone show that Morgan’s attackers also scalped him.

Scalping dates back to North American prehistory, said Guenther. Some books claim the natives learned the custom from Europeans, but it was a custom long predating white migration to the continent, he said.

The pioneers who told and retold Morgan’s tale said the warriors also yanked the sinews out from his spine to make bow strings, but Guenther said he’s unsure if that part of the story is true. That wasn’t a common practice, he said.

This Ain’t A Movie

Legends of Harvey Morgan’s battle abound, Guenther said, but you can’t trust all of them.

“In the sort of folkloric tales that have grown up in this story, Morgan and the others fired lots and lots of bullets, and there was blood and gore everywhere from dead Indians in the sagebrush,” said Guenther.

But that’s not what happened, the more reliable sources indicate.

They had just one rifle, and it was in poor condition. One report said Morgan and the others had about seven bullets.

“It’s not like in the movies where someone has endless rounds,” Guenther said.

People didn’t have money to throw around on ammunition.

If the men had had hundreds of bullets, they may have been able to scare off their attackers, said Guenther. They didn’t.

Blood In The Dusk

A few civilians traveled down the same trail later that day. In the deepening dusk they noticed signs of a fresh battle. They ducked into the sagebrush and crawled out to search for survivors.

One man crawling in the dark plunged his hand into something viscous. It was blood. He crawled around more and found one of the bodies.

The civilians rode to Camp Brown – a post of soldiers stationed to protect both the South Pass residents and the Eastern Shoshone Tribal members from hostile tribes’ warrior bands. They told the soldiers what they’d found.

The soldiers climbed the hill the next day and found the bodies. They buried Morgan, Barr and Mason in the camp burial ground near what’s now roughly the intersection of Fifth and Garfield Streets in Lander.

The bodies rested there for 37 years.

The Visionary Chief Washakie

The settlement of Pushroot grew after South Pass City’s 1870s gold rush died.

The U.S. Army shifted its fort northeast, closer to the Eastern Shoshone Tribe’s official domain.

By 1878 the military fort had a new location and a new name, Fort Washakie, to honor the tribe’s visionary chief.

Chief Washakie was special, Randy Wise, curator of Lander’s Pioneer Museum, told Cowboy State Daily: the U.S. government let Washakie choose his tribe’s reservation region as a reward for being the government’s key ally.

“He was a very forward-thinking man. He saw the writing on the wall pretty early, that he wasn’t going to stop this,” said Wise. “There was no way he could beat the hundreds of thousands of people coming out here. He made the decision early on that the Shoshone people were not going to oppose the U.S. government.”

Shoshone scouts provided lookout for explorers and military men, Wise said. The tribe and government struck a treaty in 1868.

Washakie chose the Wind River valley for his people. Commerce grew around the military fort and its needs.

“Life goes on. Lander builds around what used to be Camp Brown,” said Wise.

Lander incorporated July 17, 1890, seven days after Wyoming became a state, according to the state’s archives.

The Old Guys Remember

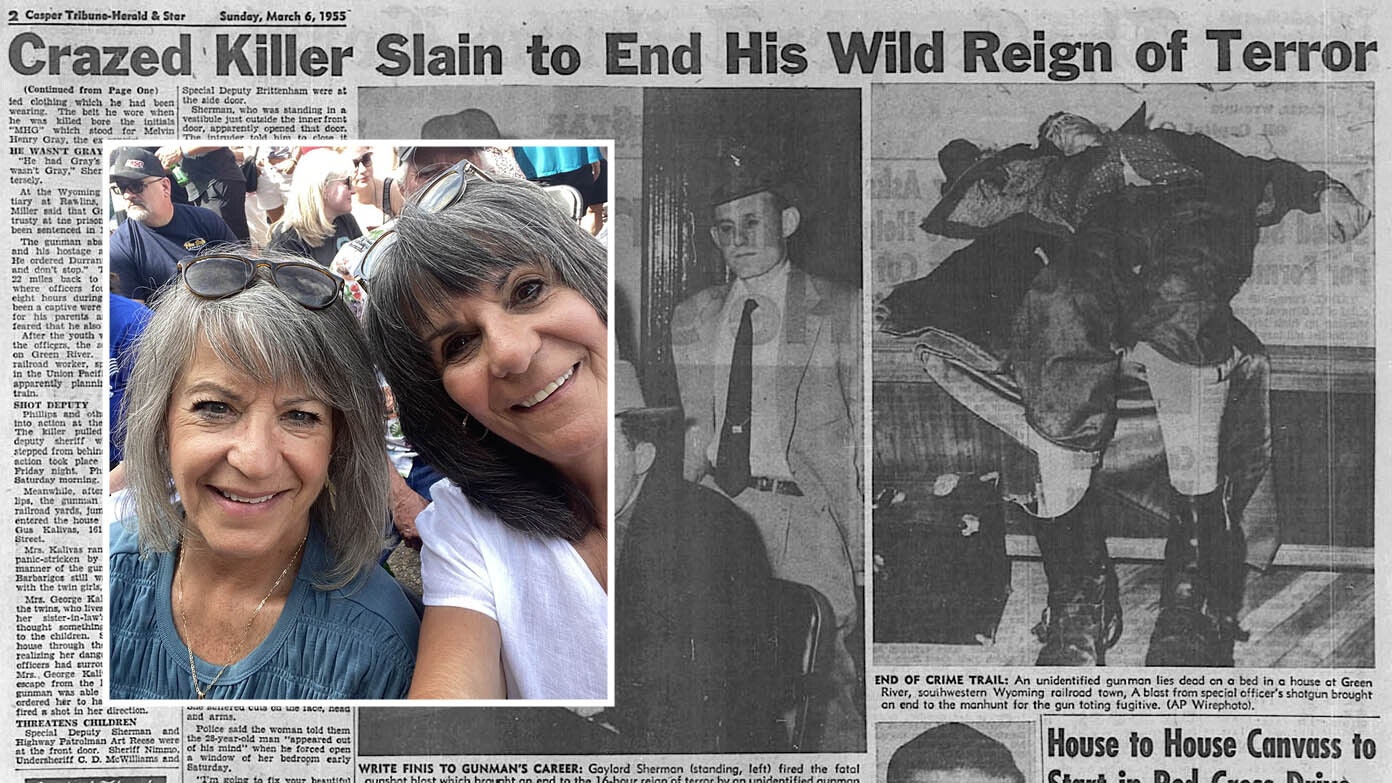

Young men dug trenches for water lines in 1907. Old men sat around and watched the young men work, “because there was no other entertainment,” said Guenther.

The diggers unearthed human bones. The old men remembered, then, that the site was Camp Brown’s military cemetery.

A digger unearthed a skull with a wagon spike lodged clean through it.

“That was Harvey Morgan,” mused the old men, according to Guenther. Then they said something along the lines of: “Boy we sure paid a heavy price for settling the West.”

Wise said the men had E.F. Chaney, a settler now in his sunset years, verify that the skull was Morgan’s.

Ed Farlow, another early pioneer, reburied the bodies at the Mount Hope Cemetery, said Wise.

But they kept Morgan’s skull.

People were already murmuring about starting a museum. Harvey Morgan gave them the impetus to build the Pioneer museum. When they finished the Pioneer Cabin and its exhibits a few years later, Morgan’s skull became the first artifact.

“They thought this was a great way to tell a story about how dangerous life was in the pioneer days of Lander,” said Wise.

Pioneer First, Cosmopolite Second

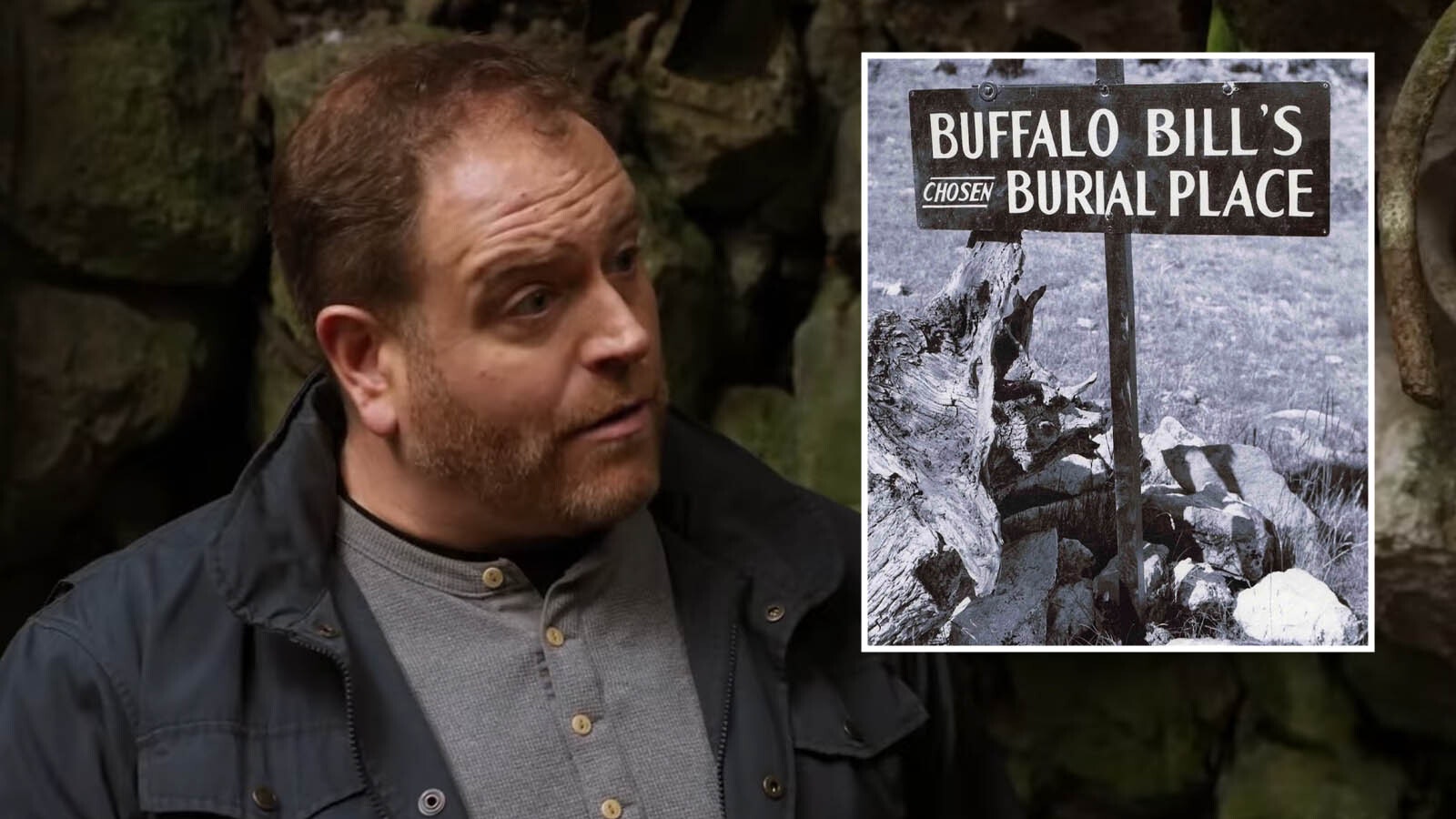

But Morgan’s skull also traveled the world with Ed Farlow, his son Stubb Farlow and Tim McCoy in 1925 and 1926. The three were silent-film actors through the 1920s, performing alongside several hundred Shoshone and Arapaho actors, Guenther said.

The three actors went on tour, lodging in Paris for a winter and performing stage screenings. They took Harvey Morgan’s skull with them.

“He was much more widely traveled in death than he was in real life,” said Guenther.

Wide-eyed European audiences of 100 years ago beheld the same deathly artifact that now sits in Lander’s Pioneer Museum.

Trembling Piano Hands

Morgan’s skull also did a stint in the Lander Odd Fellows Hall before the museum opened officially.

Loucille Adams, a Lander woman who used to tell Guenther stories about the town’s early years, locked eyes with Harvey Morgan over the Odd Fellows’ piano when she was a little girl.

“Her dad arranged for her to take piano lessons at that time, and she had to practice,” said Guenther with a chuckle. “That skull would be sitting on the shelf over the piano, and it just terrified her.”

Settlers Squeezing

There’s some debate about which tribes comprised the deadly war band, said Wise.

But Guenther said they were likely Arapaho and Sioux allied warriors. They weren’t hunting anyone in particular: the region was just a war zone in those days.

“It was like Ukraine. One gigantic battlefield,” he said. “There were war parties of Indians and whites, patrolling all over the place almost constantly – and just constant warfare.”

When Fremont County’s namesake, famed explorer and U.S. Army officer John C. Fremont passed through the Sweetwater Valley 30 years earlier, he called it “the war ground of the Snake and Sioux,” said Guenther.

“Snake” is an old name for the Shoshone.

Washakie’s Shoshone tribe had its fair share of enemies. And Washakie himself was “brutal to his enemies,” said Wise.

“He was an incredible warrior. He certainly killed plenty of Crow and Lakota,” he added. “It’s not like he didn’t have blood on his hands.”

Almost everyone had blood on their hands, said Wise.

“That’s what I think is interesting about history. It isn’t black and white. There’s so many things that cross paths and weave, leaving grey areas,” he said. “No one’s exactly a good guy or a bad guy.”

But as history solidifies behind the tide of time, it leaves us with its legends – and the occasional artifact.

Clair McFarland can be reached at clair@cowboystatedaily.com.