In Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains, caches of buried treasure await — although it’s not what most people would consider treasure.

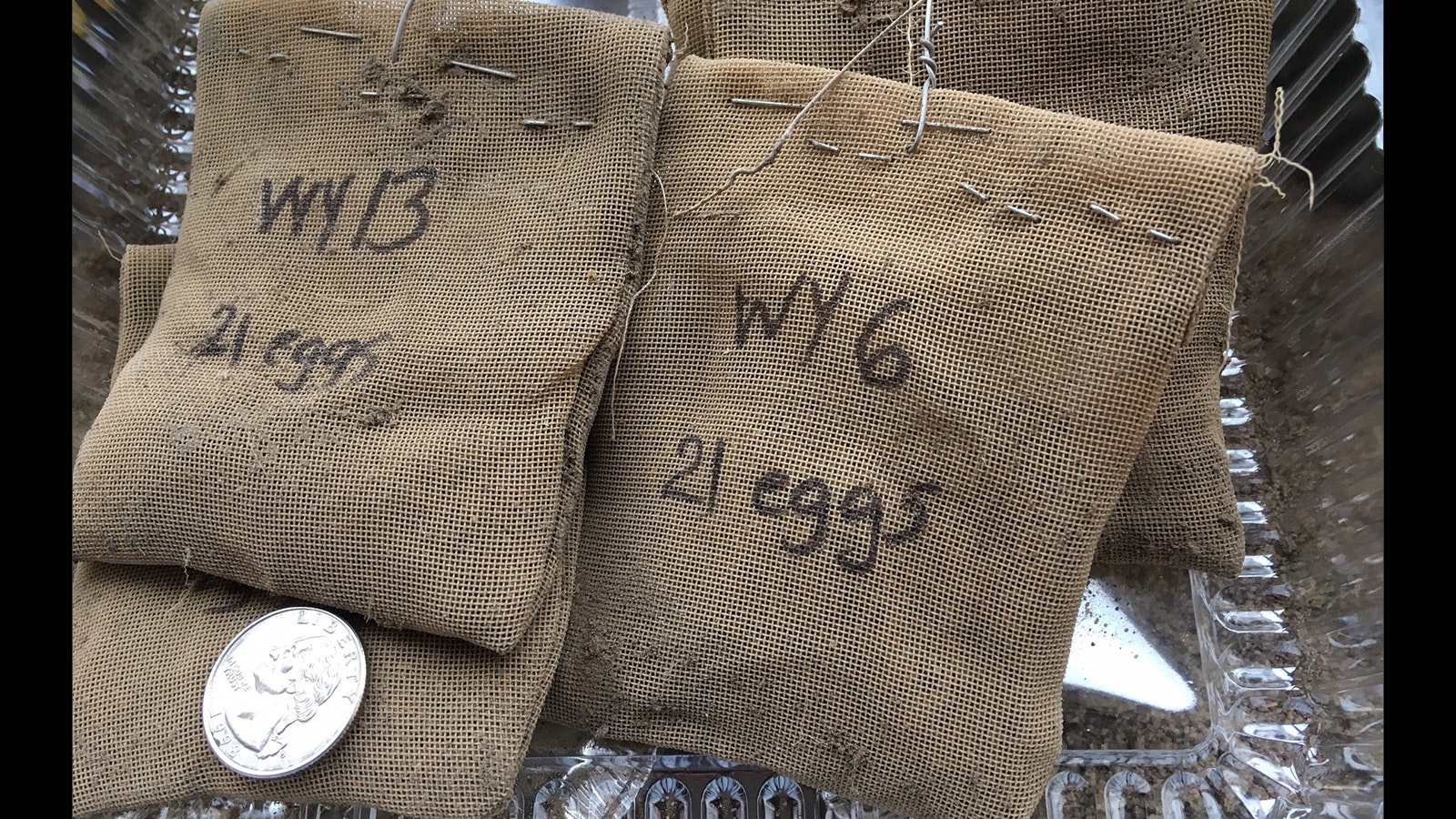

The caches are plastic mesh bags that contain Mormon cricket eggs.

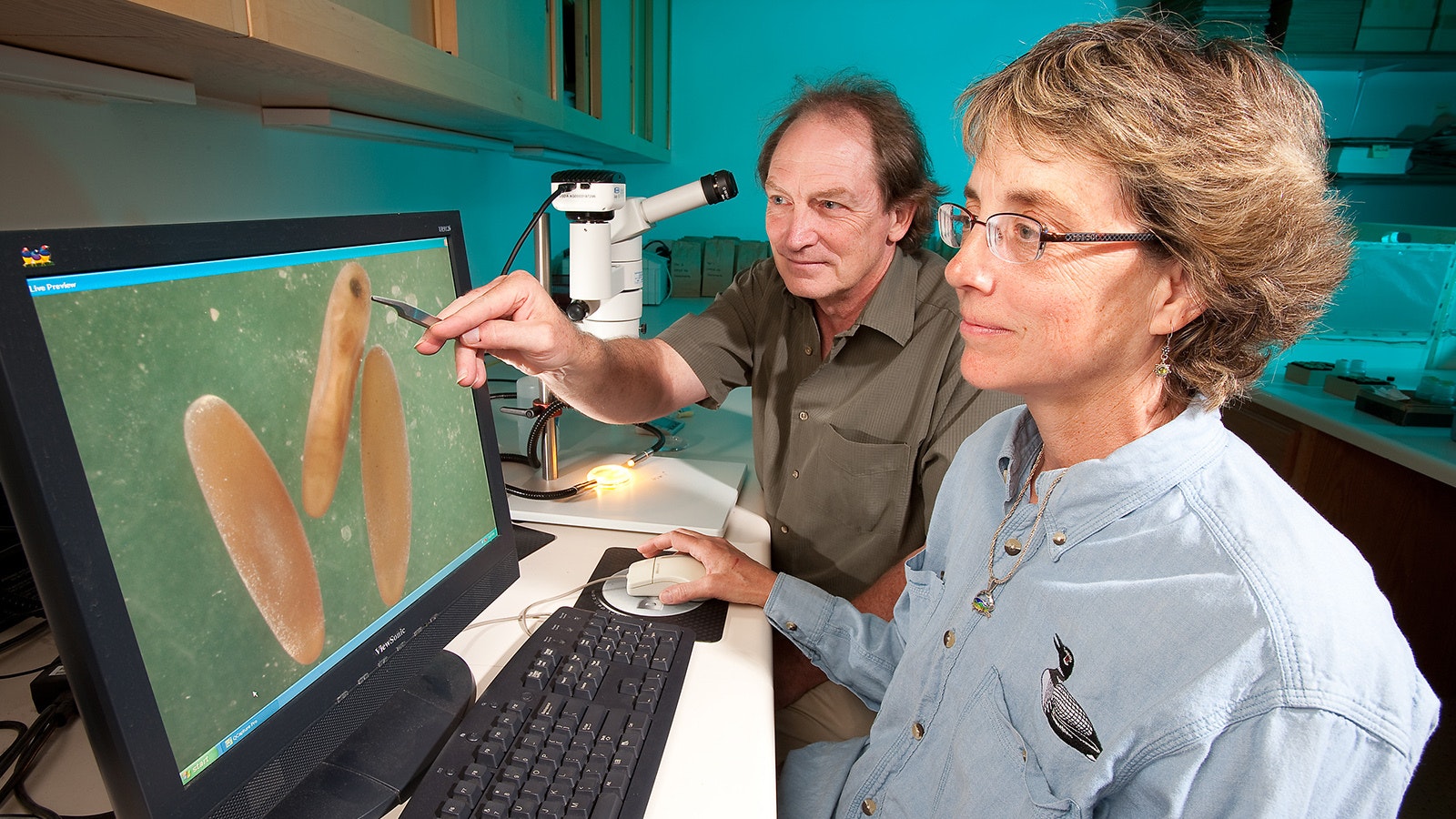

They’re part of a long-term research project by USDA-ARS entomologist Dr. Robert Srygley, who has been unraveling the secrets of the Mormon cricket’s cyclical lifestyle for 16 years.

Srygley, who works out of the Sidney, Montana, USDA-ARS laboratory, has been conducting research projects into Mormon crickets in Wyoming since 2013.

That work has included a grasshopper predation study, which verified Mormon crickets are effective grasshopper predators. That study has concluded, but the burial of caches of Mormon cricket eggs at varying elevations, ranging from 4,000 feet at the lowest to 9,000 feet at the highest, has been ongoing now for better than eight years.

“They’re taking a lot longer to develop at the high elevation than at the low elevation,” Srygley said, which is the reason for the study’s length. “The ones in the low elevation, half the eggs hatch within two or three years. The high elevations will be at eight years this year and we still haven’t had, there’s one side where we still haven’t had half the eggs (hatch).”

A Potential Natural Predator

While doing the egg study, Srygley believes he’s also discovered a potential native predator of Mormon cricket eggs in the wild. That’s a potential game changer, because presently there aren’t any control agents for Mormon cricket egg banks.

“I was always finding holes in the eggs when we started planting them in the Bighorns in 2016,” Srygley said. “So, I started looking for predators.”

At first, he thought it was probably a nematode, since the parasite was finding the eggs after they were buried.

But eventually, he was able to link up what was happening to his eggs with a Smithsonian photograph of a wingless parasitoid wasp that the Bureau of Entomology had sent them from the Bighorns during the 1930s.

“The picture that I got was actually taken from somebody in Russia, an entomologist in Russia who had posted it on his website,” Srygley said. “He had a picture of it.”

With a little more research, Syrgley was able to link that particular wasp’s egg-laying habits to what he was seeing happen to the eggs he’d buried in the Bighorns.

“These guys make a little pinhole that’s right in the center of the egg,” Srygley said.

While there is another wasp that will also attack Mormon cricket eggs, that one hasn’t been spotted very often, and never in the Bighorns.

Getting both of the wasps would be ideal, Srygley said, and it’s another of his ongoing research goals.

Right now, that effort is focused on capturing some of the Bighorn parasitoid wasps for observation.

“They’re really tiny,” Srygley said. “It’s only a millimeter big.”

Their hatch times also appear to be extremely fast. The first effort to capture them missed, despite checking on the eggs every couple of weeks.

“That would be on the very lower extreme of generation time for that genus,” Srygley said.

Given the species specificity, if females are able to manage more than a generation in a single year, Srygley believes it has huge potential for bio-control, but he’s not putting all his Mormon cricket eggs in a single basket. He’s also looking at the potential for some fungal agents to use against Mormon crickets.

Right now, though, the mystery parasitoid wasp appears to be the most promising avenue.

Mormon Crickets Leveraging Different Elevations

Meanwhile, the egg study in the Bighorns will continue until all elevations have hatched out at least 50% of the eggs that have been placed.

So far, that study is showing how differing elevations can create a lot of variability in hatch times. That’s mainly due to temperature variations in the soil, Srygley said, which is a controlling factor in Mormon cricket egg development.

“Eggs build up in the shady spots, and as they get deposited, they’re very slow to develop because they’re in these egg beds and it’s at a cooler temperature,” he said. “Then they become, you know, you have a warm year or something like that. And (all of the eggs) rush to develop.

“They then emerge more synchronously than they normally would. So, it’s kind of like a super bloom in California, where you have a seed bank building up over years of drought and then you get a rain event and all the seeds germinate. But in this case it’s not done that way, but instead with temperature.”

But before the developing eggs can finish hatching out, they have to go through a winter.

That means the millions of Mormon crickets that swarmed Edgerton recently actually began last summer, Srygley said.

Another Game-Changing Discovery

Srygley wrote a 2020 paper about one of his game-changing discoveries about the life cycle of Mormon crickets, which it turns out aren’t an annual species after all. They actually have what is called a diapause, or a period of suspended development. That allows them to wait out Mother Nature in hopes of more favorable conditions.

That diapause, combined with eggs laid at various elevations, are contributing factors to cyclical outbreaks like the one in Edgerton, and the one that’s been going on in the Oregon-Idaho-Nevada area.

“You can have a really warm event which can then rush your development at higher elevations,” Srygley said. “That same thing can happen at lower elevations, too, if you have things like canyons, or you know some sort of typical topography. So, like in Arlington, Oregon, we’re looking at the effect of canyons on that same thing.”

A Commercial Use For Mormon Crickets?

This year, Syrgley will add a study on how nutrition influences hatching habits. Some Mormon cricket females will be fed high protein diets, while others will be fed low protein diets to determine if that plays any role in when the females lay their eggs.

By teasing out all of these hatching habits, Syrgley is hoping to be better able to predict outbreaks. But he also hopes to figure out how to break that diapause habit.

“(Breaking that) would enable them to be used as a protein source for chickens, fish foods and all kinds of things,” Srygley said.

People have already been purifying protein from regular crickets to make protein powder, which can then be used in foods like energy bars, he added.

“But Mormon crickets are larger,” he said. “So there have been several people who have been really interested in working on Mormon crickets as a high-protein food source.”

Mormon crickets would make great catfish bait as well, Srygley added, if their reproduction can be adjusted to something more reliable, like an annual hatch.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.