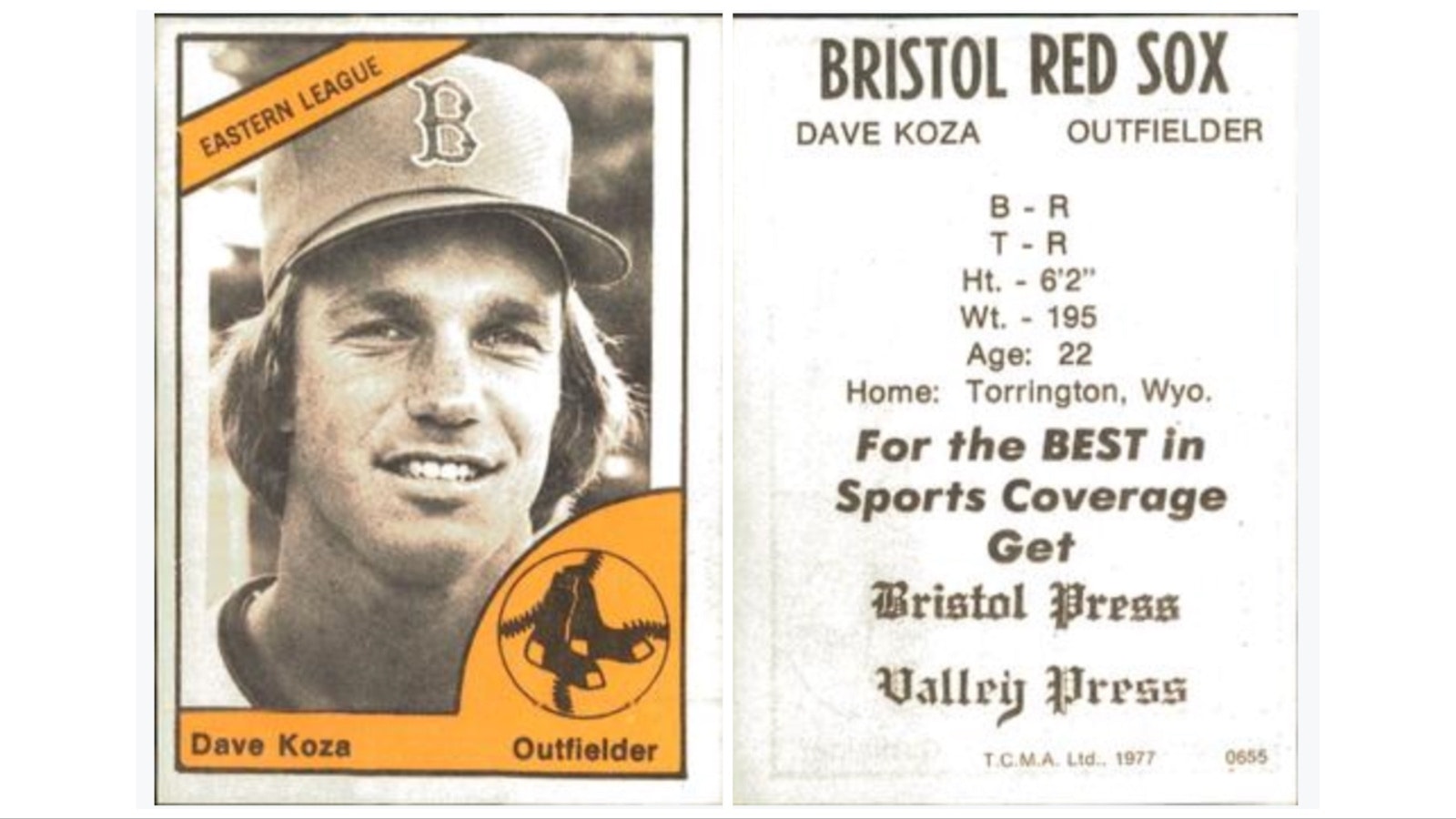

Dave Koza’s bat is in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Not bad for a ballplayer that never even made it to the major leagues. Not for one at-bat, not for one measly bag of sunflower seeds, not a sniff of “The Show.”

The perennial minor leaguer wallowed in the obscurity of bumpy bus rides, $20 a day per diem for food and unheralded rundown ballparks throughout the New England area. Yet, never realizing his dream to play Major League baseball.

In the book “Bottom of the 33rd: Hope, Redemption, and Baseball's Longest Game,” by Pulitzer Prize winner Dan Barry, Koza is highlighted as a lovable mug who never got his break, but is enshrined in baseball lore just the same.

Koza remains a hometown hero in Torrington, Wyoming. Ask anybody who grew up with him in the 1960 and ’70s.

“I was pretty young when he was playing ball, but we all knew his name. We all knew what he did. He was already a legend in Torrington by then,” said American Legion player and umpire Gary Delgado, who grew up playing in Koza’s shadow.

High School Hero

Yellowing copies of the Torrington Telegram tell of Koza’s exploits as a high school athlete.

Star quarterback of the Trailblazers, Koza led the football team to an undefeated (9-0) season in 1971. That same year he was chosen all-state in basketball. Koza also excelled in track and field, where he was a champion in the discus throw, triple jump and long jump.

But Koza’s true love was baseball.

Too bad tiny Torrington didn’t have a high school team. It didn’t even have a Little League — until Koza’s dad started one.

On his own dime, Gene Koza bought some lumber and chicken wire, and staked out a regulation-sized ballfield on a vacant lot in Torrington.

Little League was born in southeastern Wyoming.

Koza’s parents were eventually able to send Dave to a baseball camp when he was 11. The family raised the $175 through donations from local businesses happy to acknowledge Gene’s efforts in getting Little League started in Torrington.

Koza returned the following year and then two more as camp counselor. The workouts jumpstarted Koza along his baseball path. Back in Torrington he was a standout in Babe Ruth and American Legion baseball.

“I was about 12 years old at the time I knew Dave. It was around sixth grade, maybe 1968. He was a little older than me,” said John Herdt, who went by Bryan back in those days. “He was a real nice guy all-around. Real good with the younger players, helping them develop.”

Koza Packs His Bag For The Big Leagues

Koza left Wyoming as soon as he graduated high school to pursue his dream of playing baseball. He attended Eastern Oklahoma State College for one semester. After that, it was off to Colorado Springs, where Koza played semi-pro ball in exchange for housing and a day job.

A Boston Red Sox scout saw Koza play and signed the 19-year-old to a pro contract for $15,000 in 1974.

Koza got off to a fast start in rookie ball in Elmira, New York, where he hit .298 with five home runs and 25 RBI in just 35 games.

By 1976, he was tearing up Single A ball in Winter Haven, Florida. Then it was on to AA ball in Bristol, Connecticut, and the eventual callup to the AAA Pawtucket Red Sox, where he solidified a roster spot at first base in 1979.

Koza was one step, one phone call away from the big leagues. Boston’s Fenway Park was just 40 miles away. He could practically hear the crowds cheering.

Koza never got that call, but he became famous for something else entirely.

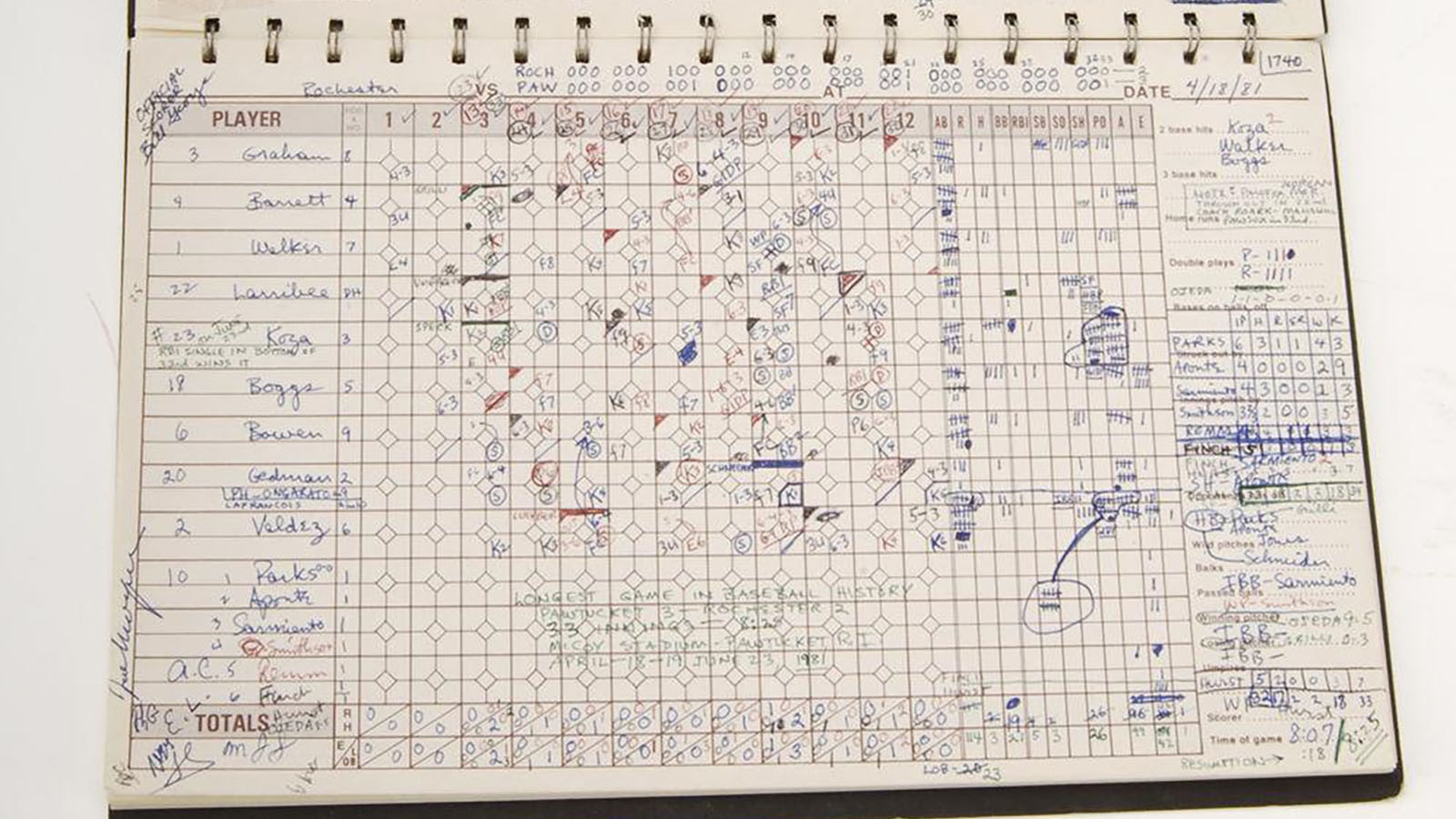

The Torrington kid had the game-winning hit in the longest game in baseball history. Freak circumstances combined to make it a record that will never be broken.

The Game That Refused To End

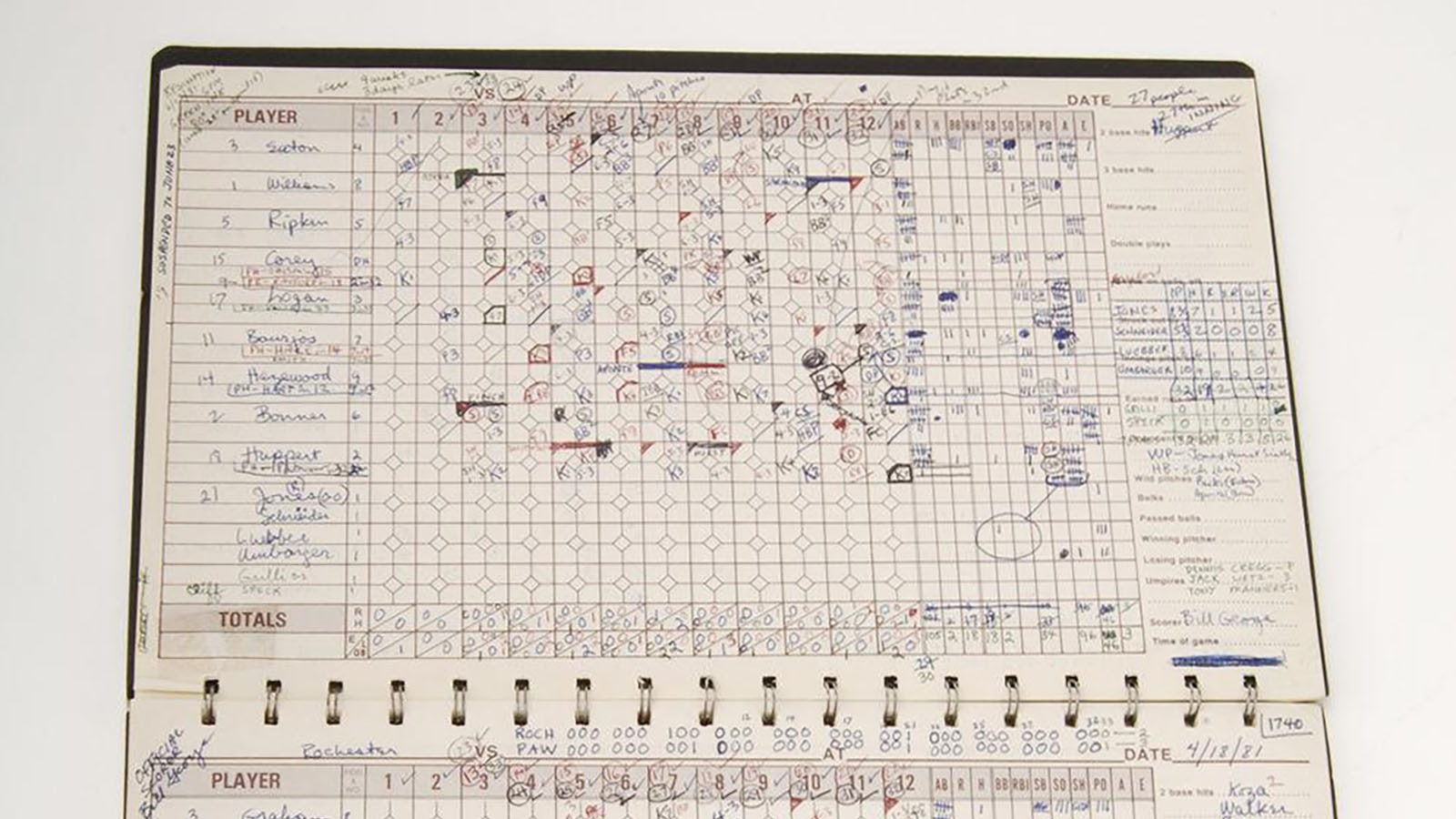

The game spanned two days and two months, beginning on a cold, blustery Easter eve night on April 18, 1981. First pitch was delayed a half-hour to fix a cranky light stand at rundown McCoy Stadium. That would be nothing compared to how long the 1,740 in attendance would be asked to sit through.

Fans had no way of knowing they would be watching a game that would go down in history as the longest ever played. Nor was it evident to anyone but league insiders that there were a dozen or so future big leaguers on the field that night — two who would be enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame decades later.

Cal Ripken Jr. was the Rochester Red Wings third baseman that night. He would go on to set a record as Major League Baseball’s “Iron Man” by playing in 2,632 consecutive games as a Baltimore Oriole.

Wade Boggs was Pawtucket’s third baseman. He would enjoy an 18-year career with the Red Sox as an all-star infielder.

Fun fact: With all that future baseball royalty on the field, it was little old Dave Koza who led both teams with five hits, including the game-winning single.

Boggs, who finished an MLB career with a stupendous .328 batting average, managed four its. He remembered phoning his father about the game the next day.

“I got four hits,” he said.

“That’s great,” his father replied.

“Yeah, but I was up 12 times,” he said.

The L-o-n-g-e-s-t Game Begins

The wind was blowing in that night like nobody’s business. Even power hitters like Koza had little chance of hitting one out.

Pawtucket’s general manager, Mike Tamburro, told the ESPN 30 for 30 podcast that, “The conditions were terrible. It was like nothing I’ve ever seen. The wind was like a wall. It was like a big monster, just slapping balls back at you.”

“I bet there was 10 balls hit that night that would have been, should have been homers,” said Rich Gedman, longtime catcher for the Red Sox who was playing that night.

On and on the game dragged, right past the 12:50 a.m. curfew.

“No game shall begin an inning after 12:50 in the morning,” the rulebook states.

But for some inexplicable reason that paragraph was left out of the 1981 version of the umpires’ handbook. And umpires stick to the rules dogmatically.

Rookie umpire Tony Maners said he was not oblivious to batters swinging half-heartedly like robots. They were freezing, exhausted, but Maners says he never once considered going against the book.

Third base umpire Jack Leitz, who was crew chief that night, backed up his ump-mate when Tamburro asked him between innings sometime after 1 in the morning when the game was going to be called.

“What about the curfew?” Tamburro pleaded.

“That doesn’t mean shit to me. There’s no curfew. It’s not in our manual,” Lietz answered.

By 1:30 a.m., Tamburro starts making calls every half-hour to league president Harold Cooper. He’s not answering. Later it is reported he was at a wedding. Or maybe he was just ignoring the phone. No one knows.

The Game Drags On

It’s approaching 2 in the morning and the concessions stand is giving away hot chocolate and coffee, trying to keep the crowd from freezing or falling asleep. There are maybe a couple hundred left.

Rochester mercifully manages to push across a run in the top of the 21st inning. If Pawtucket doesn’t score in its half of the inning the game is over and everyone can go home.

Koza leads off the bottom of the 21st with an infield double. It was actually a harmless-looking pop fly to the second baseman, but Tommy Eaton cannot make the play in that wind and Koza winds up on second base.

Boggs bats next and doubles home Koza. The crowd groaned and Boggs said he looked into his own dugout and his teammates glowered at him.

But Boggs, like almost every player on the field, did not want to lose the game no matter how long it took. The Pawtucket third baseman would later recall making three or four diving stops from innings 22-25 to keep the game tied.

And on the game went.

Crowd Dwindles, Players Play On

Players in both dugouts began burning bats in a fire barrel to stay warm as temperatures dropped into the low 40s with the wind continuing to howl. A head count showed 19 people left in the stands. They would each receive season tickets for their perseverance.

Finally, in the top of the 32nd inning, Rochester has a glorious chance to score. A ball is hit into right field to Sam Bowen. Rochester’s coach is windmilling John Hale home as he rounds third, but Bowen drills a BB to the plate to get him out.

Again, everyone left at McCoy stifles a collective groan when they should be cheering.

The 30 for 30 podcast recounts the play that embodies what it is to play the game of baseball at any level.

“I asked Bowen [later], did you ever think about not giving it your best throw, maybe throwing it over the backstop?” Barry said. “And Bowen really got angry with me. He said, ‘This is what I do. I am not going to do anything less than my best.’

“Even though this guy is never going to make it back to the Major Leagues and he knows it, he is not going to let this guy score.”

Tamburro, who was still calling the league president to try to get the game stopped, had to agree.

“You make that play in the top of the ninth, it's a great play. You make that play in the top of the 32nd, it's a historic play,” he said. “To me, it spoke to the true grit of a professional baseball player that, in the top of the 32nd inning at 4 o'clock in the morning — that he would throw out a guy at home plate in those circumstances.”

Finally, Tamburro managed to get Cooper on the phone. He explains the game is still going on.

It’s 4 in the morning, what do you mean you are still playing baseball, Cooper shouts into the phone.

“End it!” he said.

Umpire Lietz is called over between innings. He speaks directly to Cooper from the clubhouse and returns to the field with the announcement the game will be suspended. It was 4:07 a.m.

Players returned home to wives and girlfriends who didn’t believe for a minute they were playing baseball that late. Several reportedly slept on the couch. The rest of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was waking for Easter morning church as ballplayers grabbed a quick nap before their next game.

The Game Resumes

International League officials decided the game would be resumed June 23, the next time the Rochester Red Wings were in Pawtucket to take on the Red Sox. By that time, it was known all over the world that the longest game ever would resume.

More than 150 media journalists applied for credentials, including Armed Forces Radio and crews from as far away as Japan and the UK. McCoy seated just 6,000, max. There were a reported 5,746 tickets sold to fans, the rest was media. Fans who could not get into the stadium watched by standing on their cars looking over the outfield wall.

Part of the reason the resumption of the suspended marathon game drew so much interest is Major League Baseball was in the middle of a union strike by that time. No one was playing at the MLB level. This was the only game in town, so to speak.

That meant the larger and more prestigious Fenway Park was available for the game. It was offered. Players refused, not wanting to cross the picket line and content to finish this game where it all began.

“Baseball, in theory, can go on forever. And last time it just about did. It ran for eight hours and seven minutes ending after 4 o’clock in the morning with no results,” BBC reporters at the game announced to their audience as play resumed. “This in a country where they think that cricket is boring.”

End Of A Marathon

The game resumed to a World Series-like atmosphere.

“I walked out on the field and there’s cameras

and press like you’ve never seen before. It was like being in the big leagues, really,” Koza said.

It was as close as the Torrington kid ever got, anyway. He came up to bat in the bottom of the 33rd with the bases loaded and nobody out.

Cliff Speck was brought in to pitch in relief. Koza worked the count to 2-2 before Speck threw him a curveball.

“That pitch gets me out almost every time,” Koza said.

Like many farm boys from flyover states in the U.S. and countless Latin American studs who could all beat the cover off a fastball, a quality curve separates minor leaguers from “The Show.”

Koza got a piece of this one, however. Just enough to send a bloop liner over the head of Ripken and into left field. In scampered Marty Barrett with the winning run. Koza made sure he touched first and the longest game in history was over just 18 minutes after it resumed June 23.

Koza went from zero to hero overnight. After eight years as a pro, five with Pawtucket, Koza made appearances on “Good Morning America” and other national TV shows.

Not Forgotten

Two years later, Koza was out of baseball at age 29, never getting so much as an invite to the spring training roster for the Boston Red Sox. A real-life Crash Davis of “Bull Durham” fame.

Koza remained in the Pawtucket area, driving trucks and working in a freight depot, largely forgotten by Red Sox fans but not by his hometown in Wyoming.

Precious few Wyoming baseball players have ever gone on to play in the major leagues. Casper’s Mike Lansing comes to mind. The second baseman enjoyed a long career with Montreal, Colorado and Boston in the 1990s.

Casper's Mike Devereaux had a 12-year MLB career and was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles' Hall of Fame in 2021.

Then there's Tom Browning, another son of Casper, who pitched the 12th perfect game in baseball history and was a key player on the 1990 world champion Cincinnati Reds squad.

Brandon Nimmo, the pride of Cheyenne, is still playing for the New York Mets, who drafted the centerfielder in the first round in 2011.

Wyoming remains one of only three states that does not offer high school baseball as a sport. As a result, Nimmo was scouted and eventually drafted straight out of Legion Ball as an 18-year-old with the Post 6 Sixers in Cheyenne.

But Koza has one thing over any Wyoming big leaguer. The perennial minor leaguer has his baseball story etched forever in time, and his bat encased in plexiglass in Cooperstown.

“This is history,” Koza recognized immediately after the longest game ended with a 3-2 victory. “Ever since the end of the 32nd inning, I’ve been waiting for the 33rd. We’re all in Cooperstown now, and for a lot of us it’ll be the only way we get there.”

How right he was.

Contact Jake Nichols at Jake@CowboyStateDaily.com