During the 1800s, gold prospectors roamed the Yellowstone Plateau with pickaxes in search of gold. The entire area was a vast, wild potential for mineral and energy resources ready to be exploited by American industrialists.

All that came to an abrupt end in 1872, when President Ulysses S. Grant designated the area a national park and prohibited all mining within its borders.

Yellowstone National Park was the first of its kind in the United States, and for 150 years has been one of America’s true natural wonders.

Off Limits

Having been off limits to industrial development so early on in the nation’s history, almost nothing is known about what minerals lie beneath its surface. What modern technologies would have uncovered will likely never be known.

“The geologic community does not have a very good understanding of the mineral systems there beyond just speculation,” Christina George, outreach and publications manager for the Wyoming State Geological Survey, told Cowboy State Daily, adding that the WSGS wouldn’t speculate.

Besides its mining potential, very little is known about how much geothermal energy could be tapped from Yellowstone’s geysers, or how much timber could be harvested from its forests.

Of course, no one would even dream of touching this pristine landscape and much of the exploration of its geology has been entirely for scientific purposes.

Cowboy State Daily, however, thought it would be interesting to speculate about what riches would be dug up if the regulatory walls around Yellowstone were torn down, opening up the park’s 2.2 million acres to development.

Mining

In 1872, technology in resource extraction was fairly primitive by today’s standards.

Exploration for minerals, such as gold and iron, was largely done by digging around rocks, rivers and mountains.

The California Gold Rush was over and done with by the time Yellowstone became a national park. Much of the mining that was done by those early prospectors was placer mining, which included panning and sluice boxes. Steam shovels were used for more advanced open-pit mining around the beginning of the 20th century.

Today, even recreational panning is prohibited inside Yellowstone National Park. However, there has been a lot of interest in mining around the perimeter of the park. Conservationists have opposed these planned operations, and they’ve had bipartisan support.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton negotiated a land swap with a Canadian mining firm to stop its planned gold mining operation near the park.

Gold mining claims by Crevice Mining Group LLC and Lucky Minerals started another round of opposition in 2016. President Barack Obama blocked Lucky Minerals’ plans, and the Trump administration extended it 20 years.

That left Crevice Mining with the last claim, which was outside the lands blocked by the previous administrations. Just recently, a nonprofit conservation group, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, has raised money to buy the mining rights from the company and stop one of the last remaining efforts.

Them There Hills

David Miller, whose 40-year career in mining includes work in South America, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and the western United States, told Cowboy State Daily that there’s discovered gold deposits outside the park on the Montana side that have a value of at least $2 billion.

Of course, no one would seriously consider allowing mines to open in Yellowstone, but Miller said there is a type of gold mineral deposit called epithermal deposits that comes out from the boiling point of a hot spring. With all the volcanic hot springs activity in Yellowstone, there is potential for these gold deposits to be found there.

“Does Yellowstone have epithermal potential? Probably, but I don’t know of any actual deposits within Yellowstone,” Miller said.

Miller said the gold deposits that Crevice Mining Group is after likely extend inside the park boundaries. He said prior to 1999, there were some mines in the area.

When the uranium mines in Fremont County closed down, the miners went to work in those mines. Miller said he had contemplated offers to buy some of the mineral rights there and got a good look at one of the mines.

“The mineralization actually would extend into the very northern stretches of Yellowstone National Park,” he said.

A 2007 U.S. Geological Survey professional paper, “The Life Cycle of Gold Deposits Near the Northeast Corner of Yellowstone National Park — Geology, Mining History and Fate,” states that Henderson Mountain, which is north of Cooke City just outside the northeast corner of the park boundary, hosts identified resources of at least 2.3 million ounces of gold, 8.9 million ounces of silver and 130 million ounces of copper.

Yellowstone Geothermal LLC

Geothermal energy has a lot of potential to be a source of carbon dioxide-free, reliable energy. Iceland gets one-quarter of its electricity from geothermal, and 90% of Icelandic homes are heated with it.

However, the island has a unique geology. It lies over a volcanic hotspot, making it one of the most geologically active places on Earth. This is what made it easy for the islanders to get so much cheap energy from geothermal sources.

In most places, the depths that need to be drilled to tap into the Earth’s inner heat exceed what can be done cost effectively with current technologies. There are a few areas where that heat comes closer to the surface, allowing for cost-effective energy production.

One of those places is Yellowstone National Park. With many geysers, including the world famous Old Faithful, the park could provide a lot of clean energy.

Of course, no one would ever think of building a geothermal plant inside the park, and just in case anyone got any crazy ideas, Congress stopped any hope of Yellowstone geothermal exploitation with the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970. The act requires the Department of the Interior to preserve and monitor hydrothermal features in the U.S. national park system.

It’s hard to say how much geothermal electricity could be generated in the park, but Nevada currently has 18 geothermal power plants generating 600 megawatts of power. That’s roughly enough to power 700,000 homes.

All Of The Above

No one would ever seriously consider putting wind turbines in Yellowstone, including Cowboy State Daily.

However, as Wyoming is committed to an all-of-the-above energy strategy, it seemed important to include a discussion of the potential for wind energy in the park.

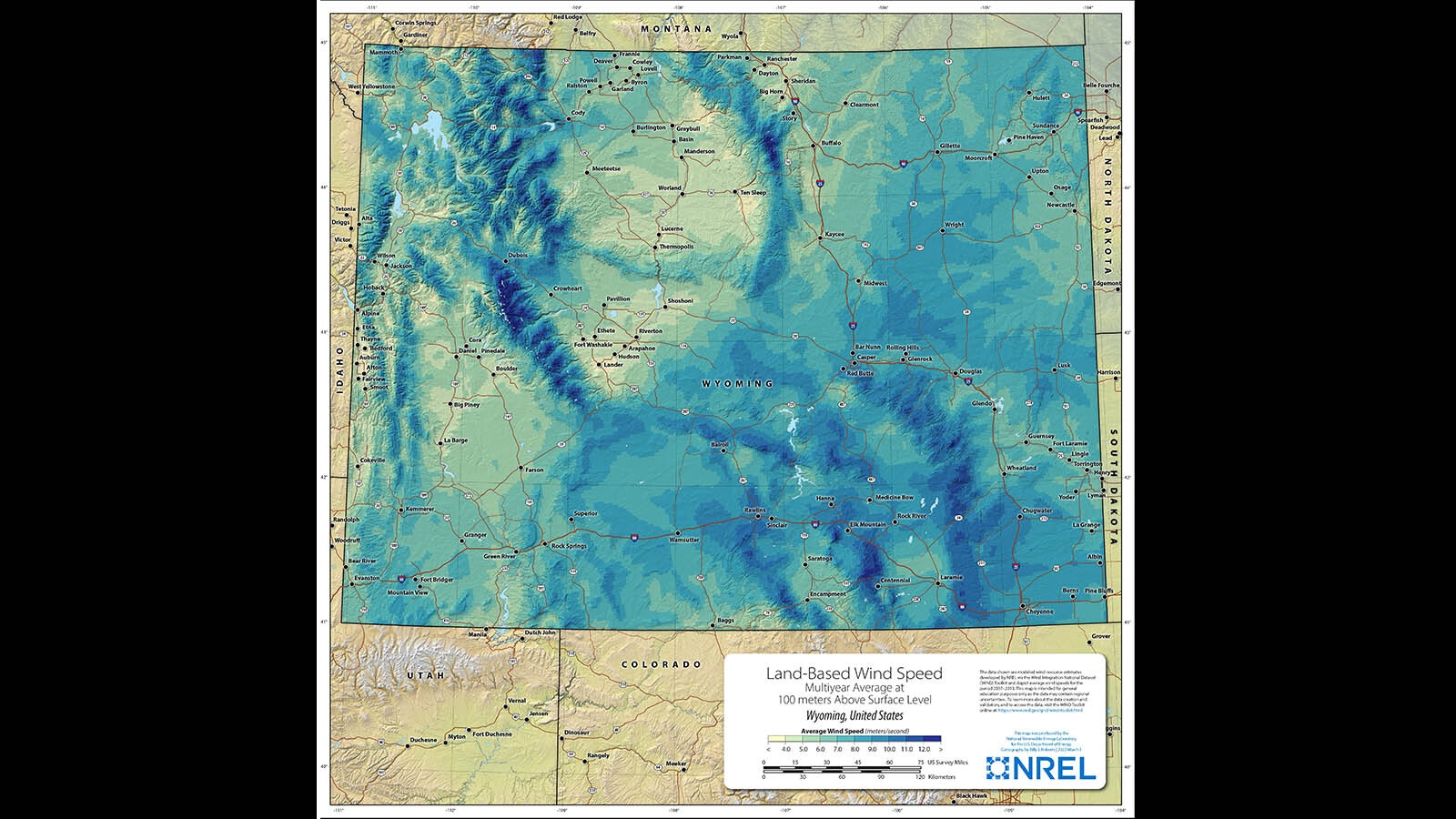

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) produces a number of maps showing where wind resources are located in the state of Wyoming at different elevations. According to these maps, there are some very good locations in Yellowstone where the wind resource could produce a lot of clean energy for California.

Most of the best spots are on the eastern side of the park, high in the mountains. The resource maps contain a lot of regional uncertainties. When wind developers site new projects, they do a lot of data collecting up with meteorological towers to determine the precise locations to place wind turbines. So it’s hard to say, based on the NREL maps, where the best wind farms would go in Yellowstone.

The other consideration for a good wind development is transmission capacity. Since no major transmission lines cross the park, these too would need to be constructed to support the Yellowstone wind projects.

Timber Harvest

Within Yellowstone National Park also are many acres of untouched forest. This includes lodgepole pine, engelmann spruce, subalpine fir, limber pine and whitebark pine. In the lower elevations of the park are douglas fir and Rocky Mountain juniper.

Forests cover about 80% of the park.

According to Forest2Market, natural pine clearcutting operations can net 86 tons of timber per acre. Assuming about 40% of the forests in Yellowstone could be harvested, a clearcutting operation taking 800,000 acres of Yellowstone’s forest would conservatively gross $2.4 billion.

Tourism

It’s hard to calculate how much revenues would be generated from all this hypothetical development.

According to a 2022 National Park Service report, the 4.9 million visitors to the park in 2021 produced a cumulative benefit — including jobs, lodging, shopping, restaurants and park fees — to the U.S. economy of $42.5 billion.

Whether or not all the mining operations, geothermal and wind energy would ever match the tourism revenues the park generates every year is anyone’s guess.

What’s certain is that the park is going to remain off limits to development until the supervolcano beneath it explodes. Until then, it generates a lot of money just being a nice place to visit.

Kevin Killough can be contacted at Kevin@CowboyStateDaily.com