Becoming a war chief of the Apsáalooke or Crow people took four difficult, but necessary deeds.

- Touch an enemy without killing him.

- Take the enemy’s weapon.

- Steal the enemy’s horse.

- Lead a successful war party.

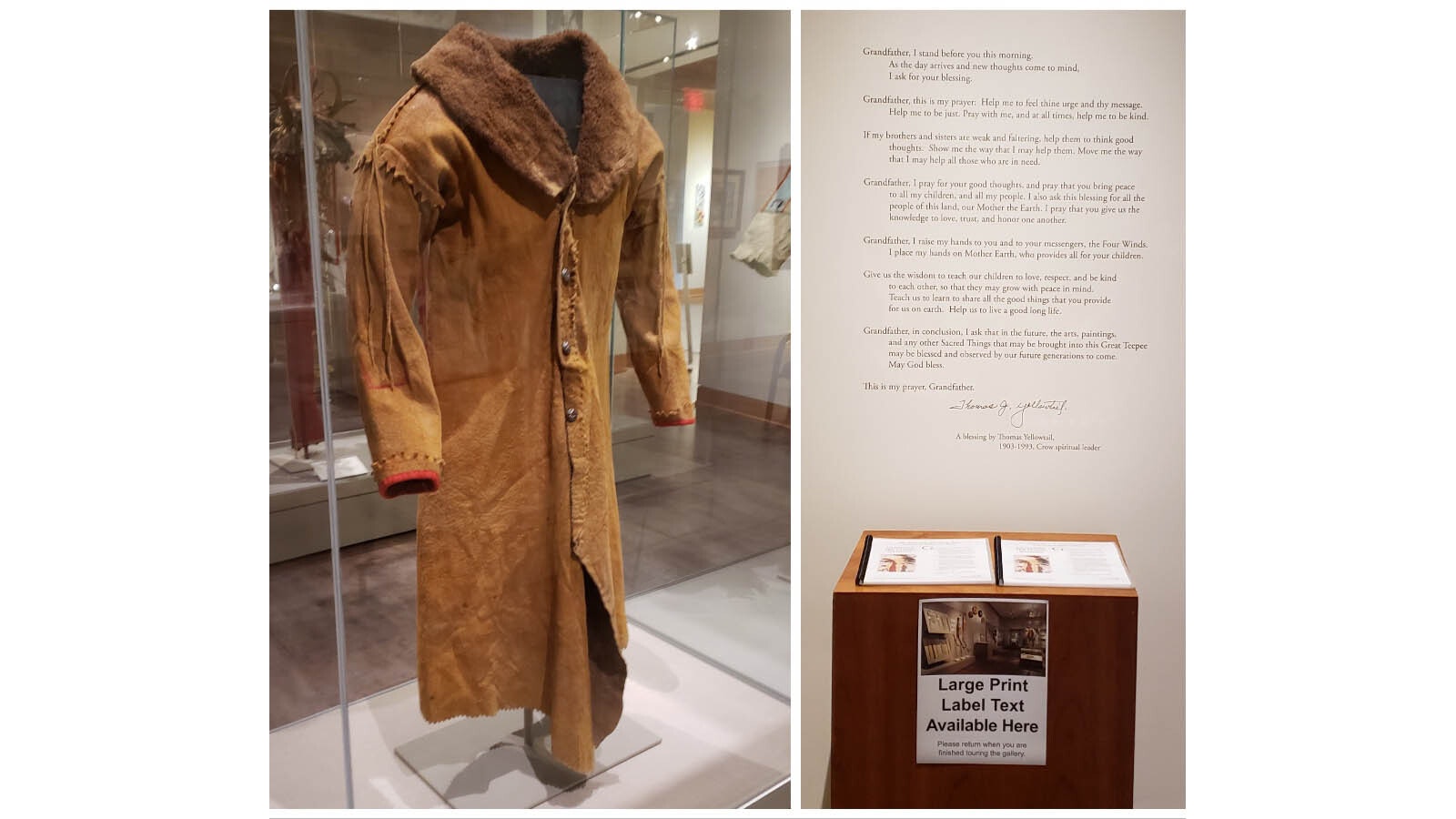

A man who completed all these tasks could wear an elk hide shirt decorated with the glass beads, red flannel and porcupine quills that together tell the tale of such deeds for those who understand what they are seeing.

This coat of many stories was typically finished with a trim of white ermine fur. First, because those animals possess tremendous fighting power, and, second, because the color was thought to protect a man in winter. It would make him invisible against the snow.

Just such a special coat is among the one-of-a-kind artifacts displayed at the three-story Brinton Museum. It’s part of the Edith and Goelet Gallatin Collection.

Today, the Brinton Museum, about 2 miles southwest of Big Horn in north-central Wyoming, is three floors and four galleries stuffed full of world-class Indian artifacts and artwork. It’s a 16,000-square-foot dream that holds thousands of high-quality artifacts, some of them worth multiple millions of dollars each.

The collection has attracted many famous visitors over the years, from Hollywood movie stars to queens, museum officials told Cowboy State Daily. Among these famous guests was Queen Elizabeth.

But it wasn’t always so.

At one time, the Brinton Museum, then known as the Bradford Brinton Memorial and Museum, was a small frame house without any real climate control and a much smaller collection of artifacts, none of them from the Gallatins.

Kenneth Schuster, its director at that time, had big ideas for the small museum, but no clear path to make any of them reality.

“The institution was basically running out of funding,” Schuster told Cowboy State Daily. “I mean, it was not technically designed to be run in perpetuity.”

The small trust set up by Bradford Brinton’s sister Helen had been what’s called a remainder trust, and it was dwindling away.

“If it ever came to the point where we could no longer open the doors to the public, the will states that things are to be sold and the proceeds would go to the state of Illinois,” Schuster recalled. “So, of course, I didn’t want that to happen. I liked my job here, of course, and I had great plans for the institution.”

But for a time, that future looked impossible and dark.

The Brinton was on the brink.

Friendships Matter

As it happened, the late Forrest Mars Jr. — the Mars bars and M&M’s candy magnate — was living right next door to the museum.

“He was at my house for some dinner, and I don’t know whether it was a birthday dinner for one of my kids or something like that,” Schuster said. “But we got to talking about how long we’ve been in the Bighorn, and I said, ‘Well, I’ve lived in the Bighorn longer than I have any place else in my life.’ And Forrest at the time is probably 74, 75, and he goes, ‘Me too.’”

That “me too” connection was the first of many to come in a friendship that developed over the years.

“We became very good friends and he … turned out to be one of the very best friends I’ve ever had,” Schuster said. “In more ways than one.”

When Mars heard about the troubles for the Brinton Museum, he didn’t have to be convinced to save it. He was eager to become its champion.

The Yale Connection

“Bradford Brinton was a Yale man, like Mars,” Schuster told Cowboy State Daily. “And Forrest loved the West. I think he had one of the largest ranches in Wyoming and Montana at the time of his death, the Diamond Cross. He really loved the area.”

That history and that love of Wyoming proved to be a tie that binds.

Bradford Brinton in 1923 had bought the final 650 acres of what had been known as the Moncreiffe Ranch, renaming it the Quarter Circle A Ranch. Tours of the ranch complex, which include a number of buildings that still dot the ranch today, are available starting in June. In addition to the mansion, there’s a green house, a leather workshop, outbuildings like Little Goose Creek Lodge, the historic Brinton Barn and more.

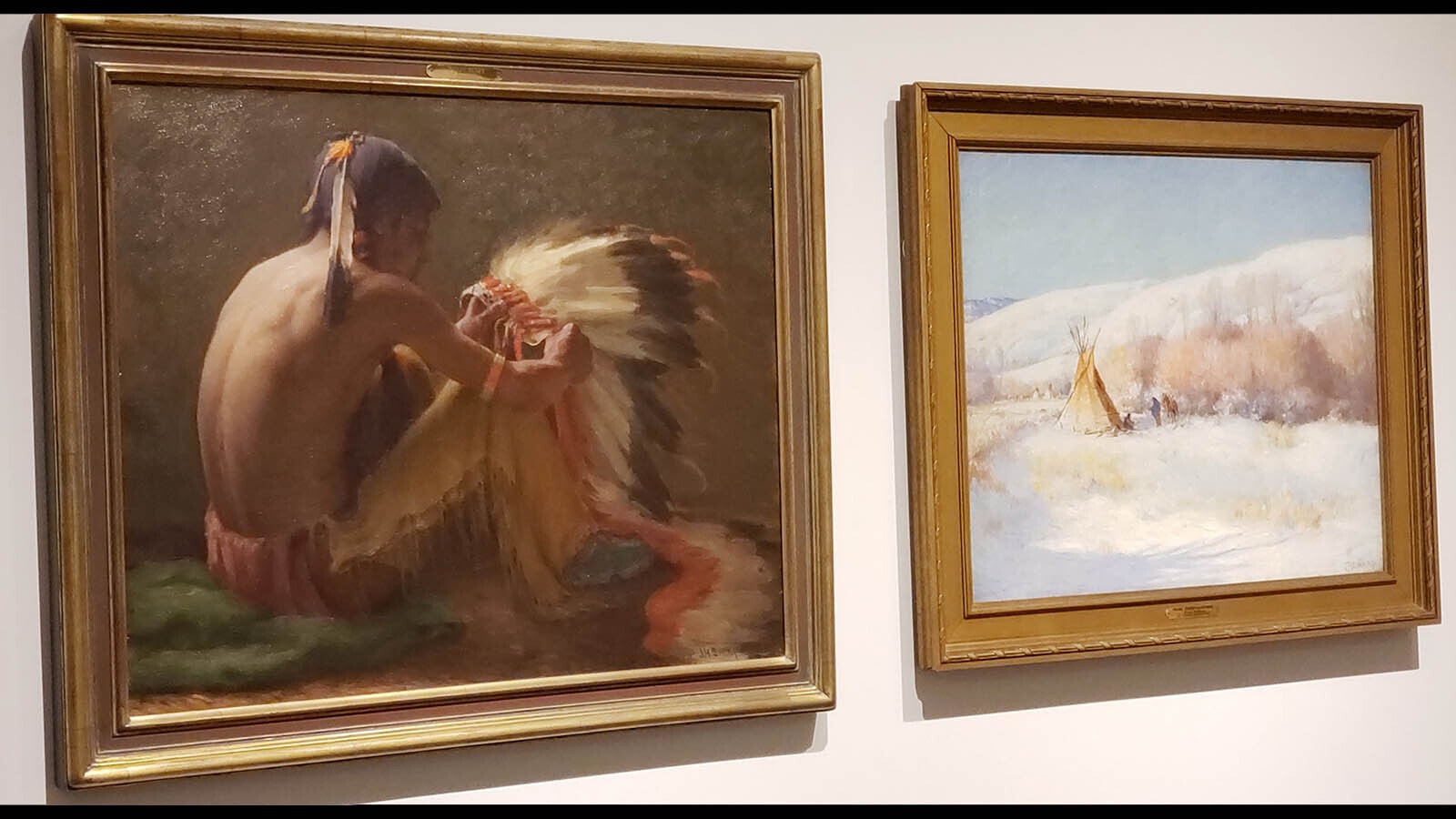

The ranch house includes art by Charles M. Russel and many others famous in the day, as well as period furnishings collected by Bradford Brinton.

But the biggest portion of that historic Moncreiffe Ranch, to the east of where the Brinton Museum is now, belonged to the Gallatins.

“Edith Gallatin had become very good friends with Apsáalooke or the Crow people,” Schuster said. “She was so well-loved, they started giving her artifacts, and I’m sure over the course of time that the Gallatins have purchased artifacts as well.

“But (she) was also asked to keep some sacred objects and, in order to keep those sacred objects, she was made an honorary Crow medicine woman.”

Over the years, the collection grew into something quite marvelous, Schuster said.

To keep it safe after her death, Edith Gallatin eventually donated it to the late Father Peter J. Powell and his foundation for the Preservation of American Art and Culture.

At that time, Powell was in Chicago, so the collection was placed on loan there with the Art Institute of Chicago.

“When I visited the Art Institute for the first time after becoming director of this place in 1990, I was amazed to find that their Plains Indian collection was just about 90% from the Foundation for the Preservation of American Indian Art and Culture. So, it was mostly that Gallatin collection. And it’s a very fine collection. I mean, it’s world-class.”

Bringing The Gallatin Collection Home

It had always bothered Powell that such a collection, with such close ties to the Brinton Ranch, was located so far away from home.

It also bothered Mars when Schuster told him of it. The first thing he wanted to know was what would it take for Father Powell to bring it back to Wyoming.

The artifacts, Powell told Schuster and Mars, needed a museum-quality space, with atmospheric and lighting controls geared toward preservation. The old Brinton Museum was a wooden frame house that had none of that, and it was far too small.

It would take an entirely new museum, and it would cost millions — $16 million in fact.

Mars wasn’t deterred at all. If that’s what it took, then a new museum it would be. But not one that towered over the Brinton family’s ranch, overshadowing it.

Mars and Schuster envisioned a museum built into the hillside — with the North America’s largest rammed-earth wall — and three floors full of artifacts and art that would include the Gallatin collection, as well as other worthy and significant items, including two that Mars himself bought for $12 million.

Another large rammed-earth wall people might be familiar with is the Great Wall of China that has stood for 2,000 years.

The Brinton Museum’s rammed-earth wall is expected to last at least two millennia, if not more, given that it incorporates modern strengthening elements. The north arc of the wall roughly encompasses the sacred medicine wheel 47 miles to the west-northwest in the Bighorn Mountains, while it’s south arc roughly takes in the Moncreiffe Ridge 4 miles to the southeast where the Bighorns meet the foothills.

The symbolic significance was carefully designed to bring together the physical and spiritual elements of the museum’s collection. Even without knowing that, the striations, which were created by adding varying amounts of iron oxide as a pigment, look pretty darn cool.

The Indian artifacts, meanwhile, are housed in glass cases so they can be seen from every angle and fully protected from oxidation. Lights turn on and off automatically, depending on whether anyone’s in the exhibit looking at it, which reduces the amount of time the artifacts are exposed to light.

“The whole exhibition is (displayed) in very much the manner that father Powell deemed necessary for it to be really the most impactful,” Schuster said. “And, of course, the collection is sacral in nature, because the art, you know, these things are part of the heritage and part of the spirituality of the native people.”

Elevating The Senses

The Brinton Museum created by Forest Mars is, as he and Schuster envisioned it, an elevated experience in all senses of the word.

The experience includes a brunch/lunch bistro with things like grilled portobello salad, shrimp quesadillas and beef bulgogi ramen, along with craft beers and seasonal drafts from Sheridan microbrewer Luminous Brewing.

Perched at 4,250 feet, the bistro offers diners a view of the Bighorns out either of two windowed walls. On a cloudy day, one’s eyes are level with the mountain tops, which are brushed by the feathery wings of clouds. Truly divine.

The bistro was Schuster’s idea.

“We put the bistro on the top on that side of the building because you could have that view and, you know, I always wanted visitors to, because everything before that building took place down her tin the Valley and nobody could ever really see how beautiful of a view it was or how this ranch fits into the area,” Schuster said. “And what a magnificent view it is.”

The Gift

After eating in the bistro, there’s always plenty of artwork to see, with three floors and four galleries — food for thought and the soul. Visitors who return will find new things they didn’t notice the last time no matter how many times they come back.

Each artifact includes notecards explaining the significance of the item, putting it into historical context. It creates new perspectives, even for the most knowledgeable history buff.

Artwork from the period also hangs on the wall, including paintings by Standing Bear — a contemporary friend of the famous Lakota medicine man and spiritual leader Black Elk, who was born in Wyoming a few years before European settlers came to America and upended the world he lived in.

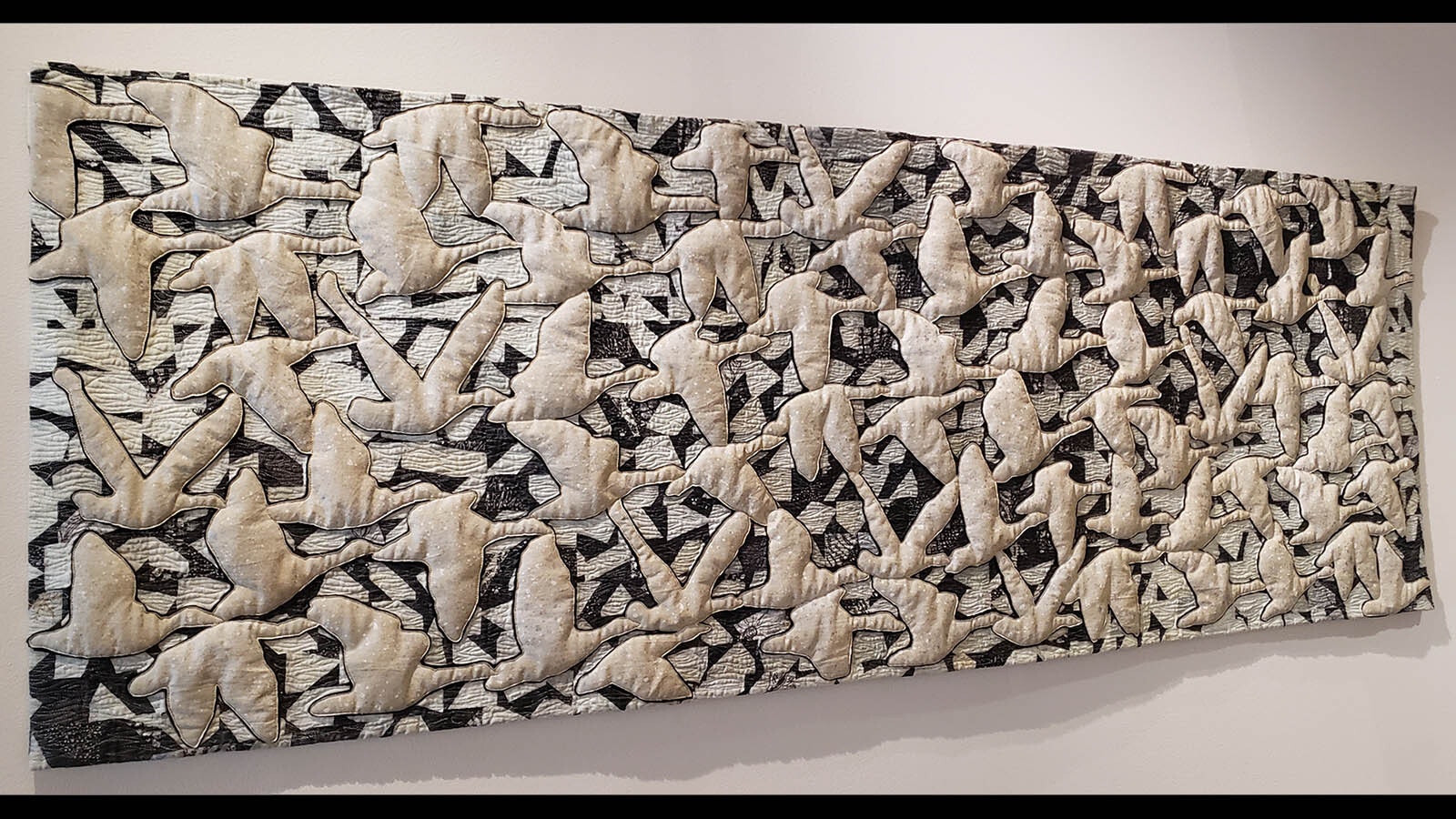

Traveling exhibitions also come to the museum. The one there now is called “The Gift,” and it tells the story of the White Buffalo Woman and the sacred pipe she gave to the Lakota.

The pipe was a bowl made of red stone to represent the flesh and blood of the Buffalo people and all other people. The wooden stem represented trees and plants — all the good and green things growing on the earth.

The smoke passing through the pipe is the breath of man, carrying prayers up to Wakan Tanka — the Great Spirit and creator of all things.

Contact Renée Jean at Renee@CowboyStateDaily.com