“Pain is the rent I pay for living in this body.”

It’s a line from Rod Miller’s poetry book, which published this month, and is one of many verses insisting that pain, cold and loneliness are the dark, thick lines with which a cowboy sketches beauty.

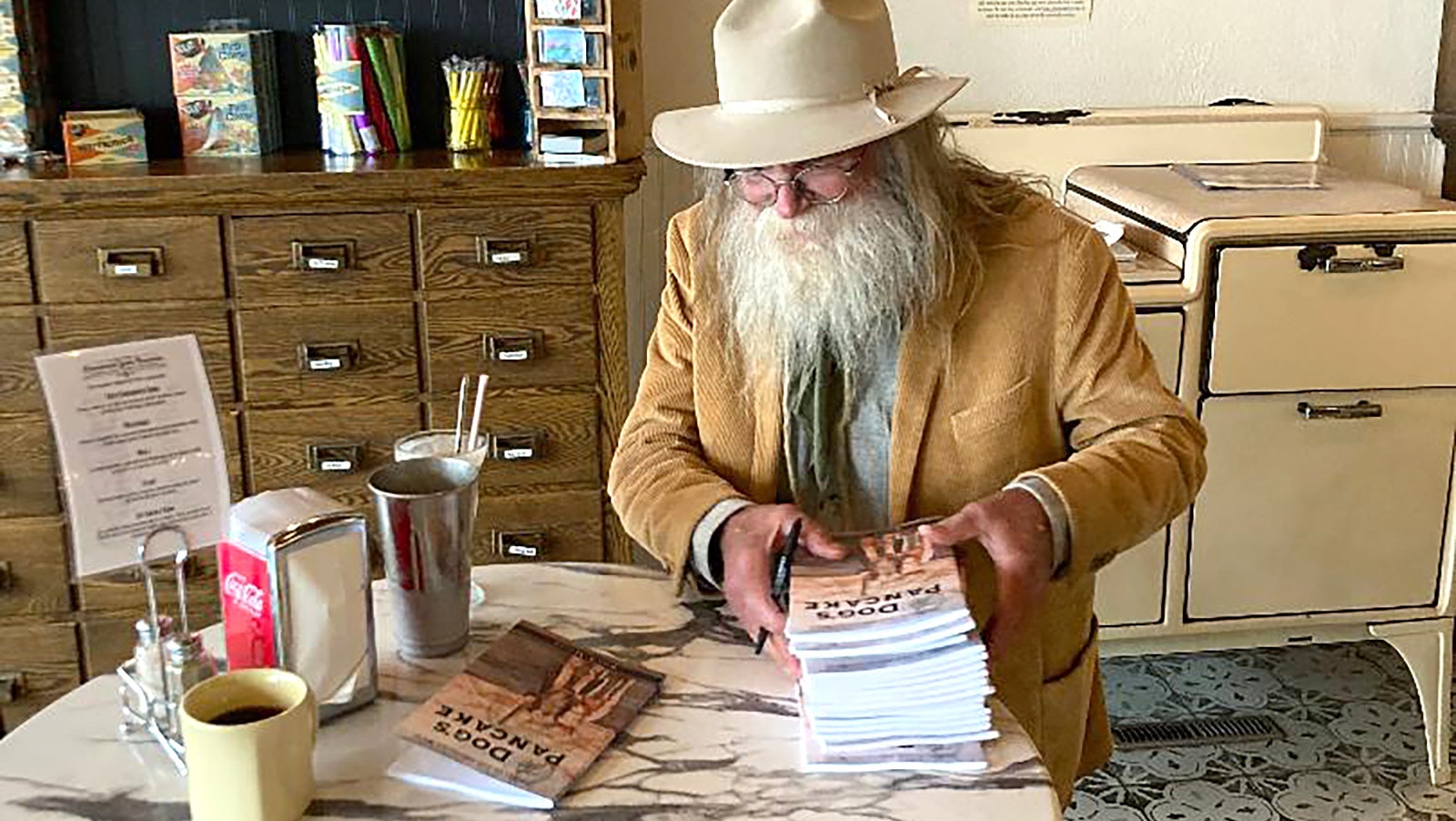

The collection titled “The Dog’s Pancake” pulls together 65 poems, mostly free-verse, about life in Miller’s home state of Wyoming.

The poems imagine that the coal in Wyoming tumbled from chaos to order just so that a radiator could heat a pair of socks. They warn of sharp winters and lonely obsidian nights, and jumble nature’s caprices with women’s whims.

Breakout

Miller often jokes that patience is the last virtue he has left. But the 72-year-old needed it: This is his first time publishing a collection of poems. He sent poetry to publishers for decades without any results.

When the time was right, it was the publisher who found Miller, who now lives in Cheyenne.

Laura McCormick of High Plains Press reached out to him last year as he reclined into retirement from ranching and politics.

The poetry collection is not his first published work altogether, however. Miller published a novel, “Apologia of the Fat Cowboy,” about 15 years ago.

“The Dog’s Pancake” is a rough first poetry volume, he said, which is why he chose its title from a poem about tossing the first, burnt pancake off the griddle to the dog.

“I thought the title apropos,” said Miller in an interview with Cowboy State Daily.

Pain

He’s only half right.

The cowboy anthems are “burnt and crunchy” in theme, but their language is mighty, sometimes startling.

Wyoming’s beating wind drives a housewife mad in one poem. In another, a man can smell his woman on the first drops of rain.

The sunrise shocks a man out of his corporeal shell of pain in “The World At Large.” But the reader can’t be sure if that painful body is an actual person or the tough, empty hills of Wyoming.

“Yeah, you could read that metaphor on two different levels,” said Miller. “One (shell) is the physical place you’re in. The other is your body.”

Whichever way the metaphor works, “mine has not been a pain-free existence,” said Miller.

Pain teaches men what to do, and what not to do; how to grow up and finish the work that each new day demands, he said.

Winter

Miller said he’d take pain over cold any day. And yet the cold is more faithful to him. It rakes through the volume, even when the poet tries to ignore it.

In the poem “Winter,” Miller calls the season “my most faithful mistress. Her constancy is fearsome. … One night, soon, she’ll return, lingering kisses from frigid lips.”

That’s just reality in Wyoming, he said.

“I’ve spent a lot of my winters outdoors doing hard, cold work,” he said, remembering decades spent on his family ranch in Carbon County. A collection of Wyoming poetry wouldn’t be honest without some reverence of the cold.

But oh, how he hates her.

Women

Some of these poems are not for prudes, but even so, Miller said he kept his “raunchiest” poems out of this collection.

“Just like pain is an inescapable part of life, so too is … eroticism,” he said.

And he conflates it with nature, which is another powerful force he can’t control.

“I remember you so close that I smelled your wild fire just over the ridge,” reads the poem “Womansmoke.”

“From your valley,” it continues, “the rain carried womansmoke in a thousand hot kisses to my face.”

Mystery and attraction are one half of the eroticism. The other is heartbreak. And Miller stabs the reader with that sensation as well.

The brooding cowboy in “Mercury” is left to split wood, alone, for the coming winter — “it’s winter’s only crop.” He knows that his woman is not coming back.

She left before the solstice when the world was still warm. Only the cowboy’s grueling work and a trickle of whiskey can warm his heart now.

It’s one of Miller’s only rhyming poems. He rhymed in accordance with his muse’s will, but against his own.

“That’s just how the poem came to me,” he said, noting that usually a rhymed structure feels contrived to him. “I heard it rhyme in my head before I wrote it.”

Horses

Women and nature do what they want, but horses may be reasoned with. As long as you’re patient.

“I can stand here for an hour, letting you smell the back of my hand with your flared nostrils … while you memorize my presence,” reads a poem called “Youngblood” about waiting — and waiting — for a horse’s favor.

The cowboy has real influence over his horses, but he doesn’t take it lightly. The horse’s relational bonding and trusting servitude, like man’s, must end in death.

So the cowboy remembers his own fate.

A poem titled “X” considers the perfect spot on the horse’s skull a man must shoot during a mercy killing.

“But before all that geometry, your heart must examine itself,” the poem says. “Before you make an X on anything, exhaust the rest of the alphabet of love.”

The dystopian “If All The Horses Were Gone” imagines a world like its title. It scours abandoned tack for signs of life, memories of purpose.

“Vacant saddles sleep with latigo draped over horn, oiled and ready, but idle — vaguely recalling the hot throb of caballo in their embrace,” it reads.

These Dark Lines

Miller said he’s grateful for his publisher McCormick, and for Ariana Fate, a Wyomingite who made the dark-whimsy line drawings opposite many of his poems.

“I’ve always been a fan of Ariana’s art,” said Miller.

He had recommended Fate to McCormick when McCormick told him he should use an illustrator.

“I thought she’d do a good job, and I’m tickled with it,” he said.

Fate drew the crows that haunt Miller in his retirement and the horses he wooed in his ranching days. Most of her drawings are immediate and sensory depictions of the poetry subjects. They verge onto the symbolic only occasionally, such as when the western suns resemble Aztec calendars, alongside poems about time.

Miller said he didn’t tell Fate what to draw. She read the poems and sketched their creatures on her own.

As with everything else in the book, they circle back to a hard-fought life in rural Wyoming.

“The Dog’s Pancake” is available at Amazon.com, HighPlainsPress.com, and in some bookstores.