Harvard University once claimed to possess up to three books in its libraries that were bound in human skin.

Thanks to relatively new technology, two of the works in question have been debunked, but not without leaving one proven authentic and opening a rabbit hole filled with questions.

First, books bound in the largest organ of humans are a thing. In fact, the practice was once more popular than one might think. Second, in response to binding books in human skin, Wyoming history says, “Hold my beer.”

The Cowboy State has an ashtray, a medicine bag and a pair of shoes all made from the remains of a notorious outlaw who met his demise at the end of a rope.

Don’t Judge A Book By Its Cover

Almost a decade ago now, the internet was abuzz with hoax-or-real tales of literary works bound in human skin, particularly a few tomes reportedly owned by an Ivy League school.

It started in 2006 after an article appeared in the university publication “The Harvard Crimson.” Written by Samuel Jacobs, who was named editor-in-chief of Time Magazine just this month, “The Skinny on Harvard’s Rare Book Collection” zeroed in on three unique books in the university’s 15 million-volume collection purportedly bound in human flesh.

Jacobs fleshes out the texts, ranging in content from medieval law to Roman poetry to French philosophy. A lawbook, for one, has been discredited in its claim to be skin-wrapped. It’s bound in flesh, but not human.

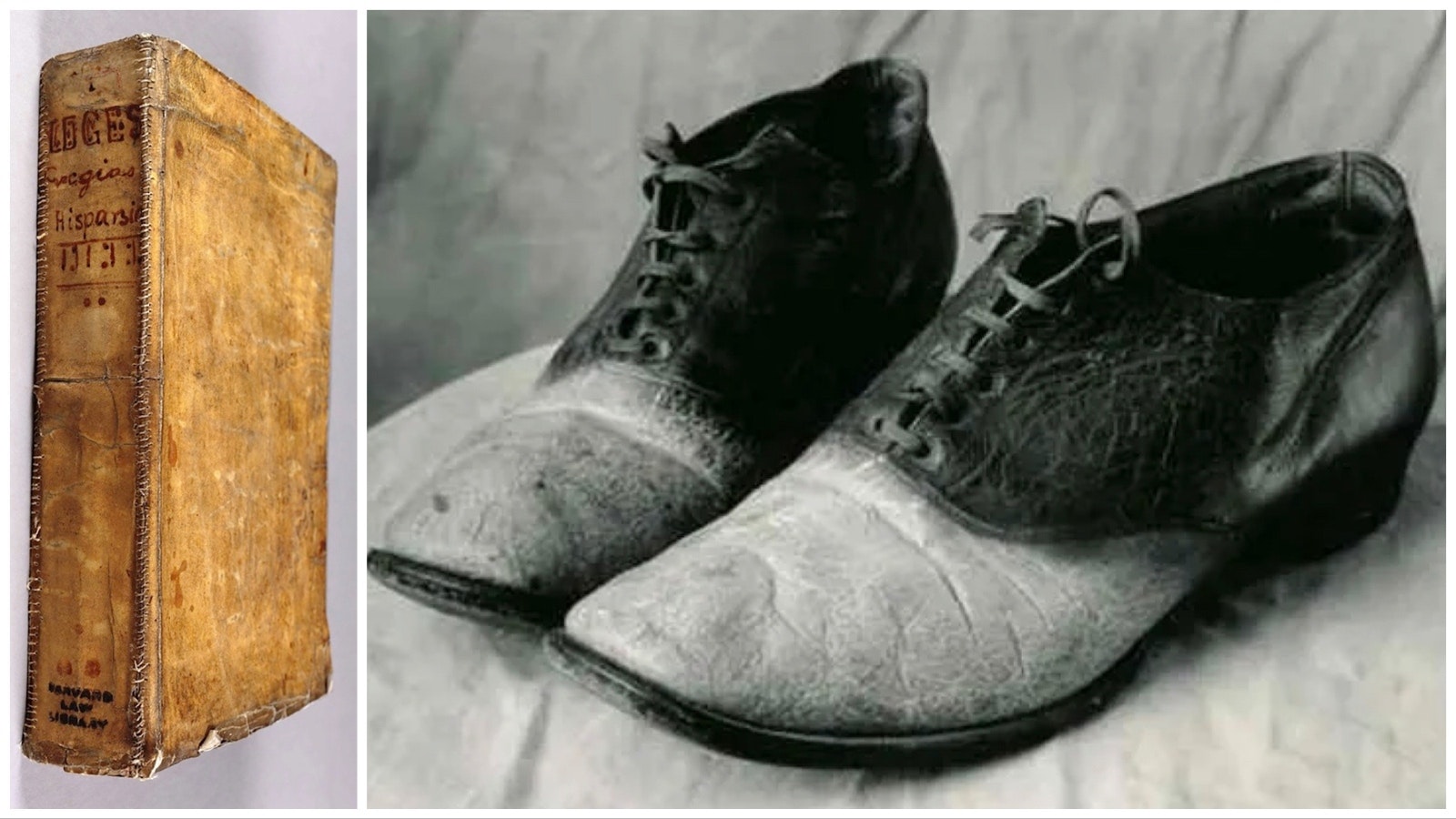

“Practicarum Quaestionum Circa Leges Regias Hispaniae” is a Spanish lawbook containing material dating back to 1605. It was bought for $42.50 from a New Orleans book dealer in 1946 and shelved in the Langdell Law Library at Harvard, according to the library’s curator, David Ferris.

Nothing about the book’s cover seems out of the ordinary, though it appears to have a hue suggestive of skin tone. It’s what is handwritten in purple ink on the book’s last page that sets one’s skin to crawling.

“[T]he bynding of this booke is all that remains of my dear friende Jonas Wright, who was flayed alive by the Wavuma on the Fourth Day of August, 1632.”

DNA tests performed in 1992 proved inconclusive. The tanning process was partially to blame, but truthfully, technology just wasn’t up to the task until more recent scientific advancements in what is known as peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) made positive identification possible.

In-house testing performed by Harvard using the analytical technique for protein identification PMF proved conclusively that Wright’s remains do not bind the 400-year-old book, nor do any human’s. The cover is sheepskin.

Another book in question — a 1597 French translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses housed in the Countway Library’s Center for the History of Medicine — also was proven to be sheepskin even though a small penciled annotation appearing on the inside cover reads: “Bound in human skin.”

The Hide That Binds

The myth busting leaves Harvard with one final volume touted as epically epidermically bound.

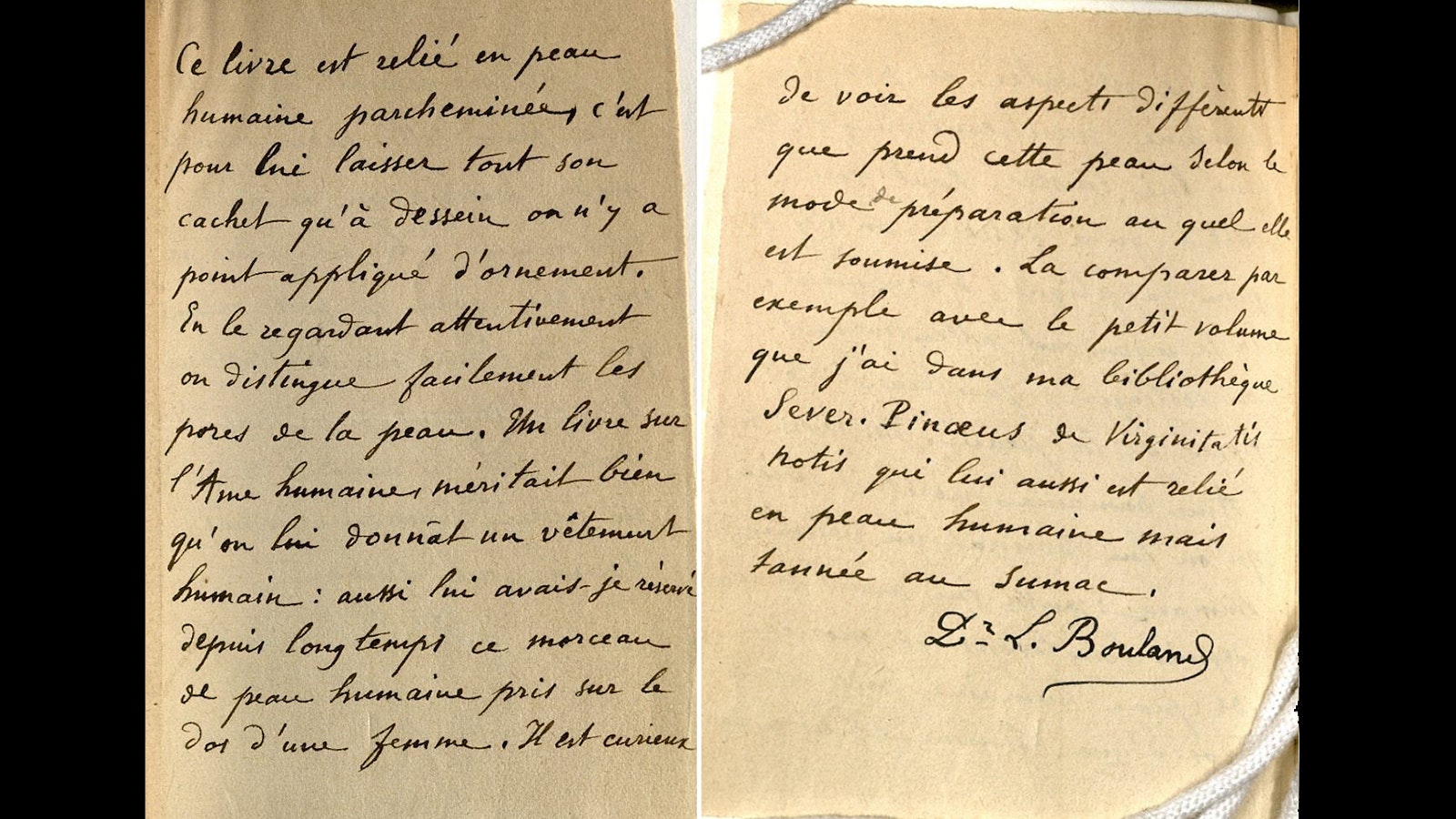

“Arsène Houssaye’s Des Destinées de L’ame” is part of Harvard’s massive Houghton Library collection. The meditation on the soul and afterlife was gifted by the author to a friend, Dr. Ludovic Bouland, sometime in the mid-1880s.

Bouland, a noted medical doctor and prominent bibliophile, bound the book with the skin from an unclaimed body of a female mental patient who had died of a stroke. A note was found inserted in the book after it was donated to the university in 1954 by the widow of John B. Stetson Jr. (yes, that Stetson, son of John Sr., founder of the famed cowboy hat company).

The two-page note is handwritten in French by Dr. Bouland. It reads, in part:

“This book is bound in human skin parchment on which no ornament has been stamped to preserve its elegance. By looking carefully, you easily distinguish the pores of the skin. A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering: I had kept this piece of human skin taken from the back of a woman.”

The same testing conducted in early 2014 that disproved Harvard’s two anthropodermic-bound books was able to confirm the binding of “Des Destinées de L’am” as most likely that of a human.

Other written works confirmed bound in human skin can be found at the John Hay Library at Brown University (four volumes) and the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (five books, including three of which came from the skin of the same woman).

Perhaps the most famous example of anthropodermic bibliopegy is a book gathering dust on a shelf at the Boston Athenaeum.

“The Highwayman: Narrative of the Life of James Allen Alias George Walton,” is a memoir of Walton’s. He narrated the autobiographical story to the warden of the Massachusetts State Prison while on his deathbed in 1837.

He insisted the book be bound in his own skin and given to a man, John A. Fenno Jr., who fiercely resisted Walton’s attempt to rob him. Fenno’s daughter reportedly gifted the work to Boston Athenaeum, but the library/museum has no written proof of that.

Literarily Interred

OK, books bound in human skin sounds revolting. But the practice was once somewhat accepted, if not common.

Termed anthropodermic bibliopegy, the binding of books in human skin dates back to at least the 16th century, according to a study released in the Journal of the American Medical Association in January 2014.

In the mid-1800s, anthropodermic binding was at its height. Historians cite several reasons for the macabre practice.

Confessions of criminals were sometimes bound in the skin of the convicted by court order. Doctors and scientists also helped popularize the gruesome fashion, sometimes binding medical journals and texts in epidermic. Family members were also sometimes literarily interred as a memorialization.

Since PMF made testing more accurate, dozens of suspected books have been analyzed. A team of scientists (Anthropodermic Book Project) comprised of anthropologists, bioanalytical chemists and the like, have tested more than 50 volumes to date, of which 18 were confirmed as human, 13 not human and 31 as yet undetermined.

One rare book considered by those in the antiquarian book trade to be the “Holy Grail” of skin-covered tomes tested false for human skin.

Notre Dame University’s Hesburgh Library alleged to possess an anthropodermic bibliopegy — a 1504 philosophy book once thought to be owned by Christopher Columbus and bound in the skin of a Moorish chieftain. It turned out to be pigskin.

Notorious Wyoming Outlaw Becomes A Pair of Shoes

Well before it officially became a state, the rugged Wyoming Territory was a haven for highwaymen, cattle rustlers and cold-blooded killers.

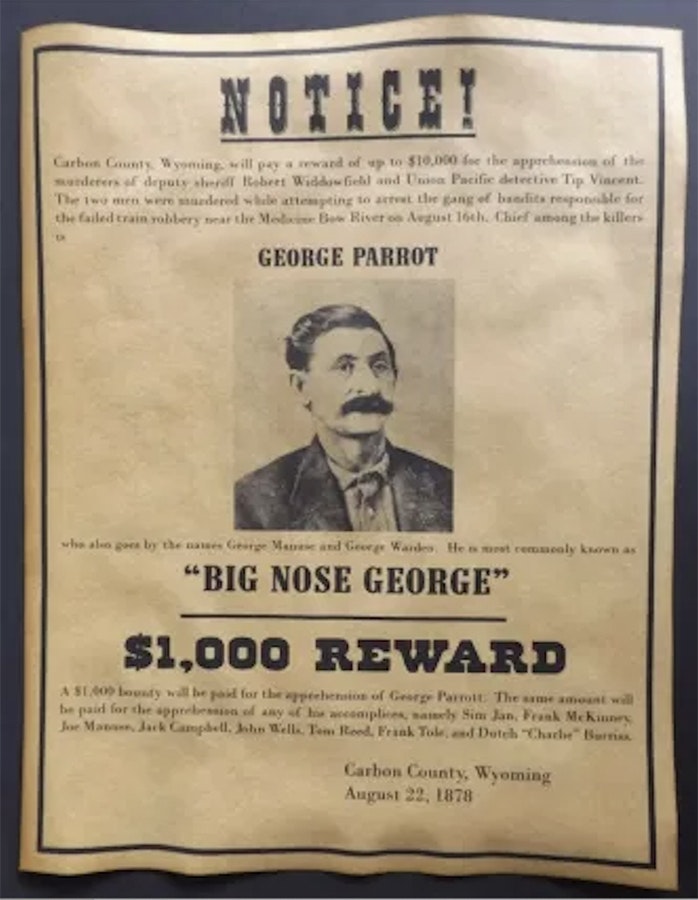

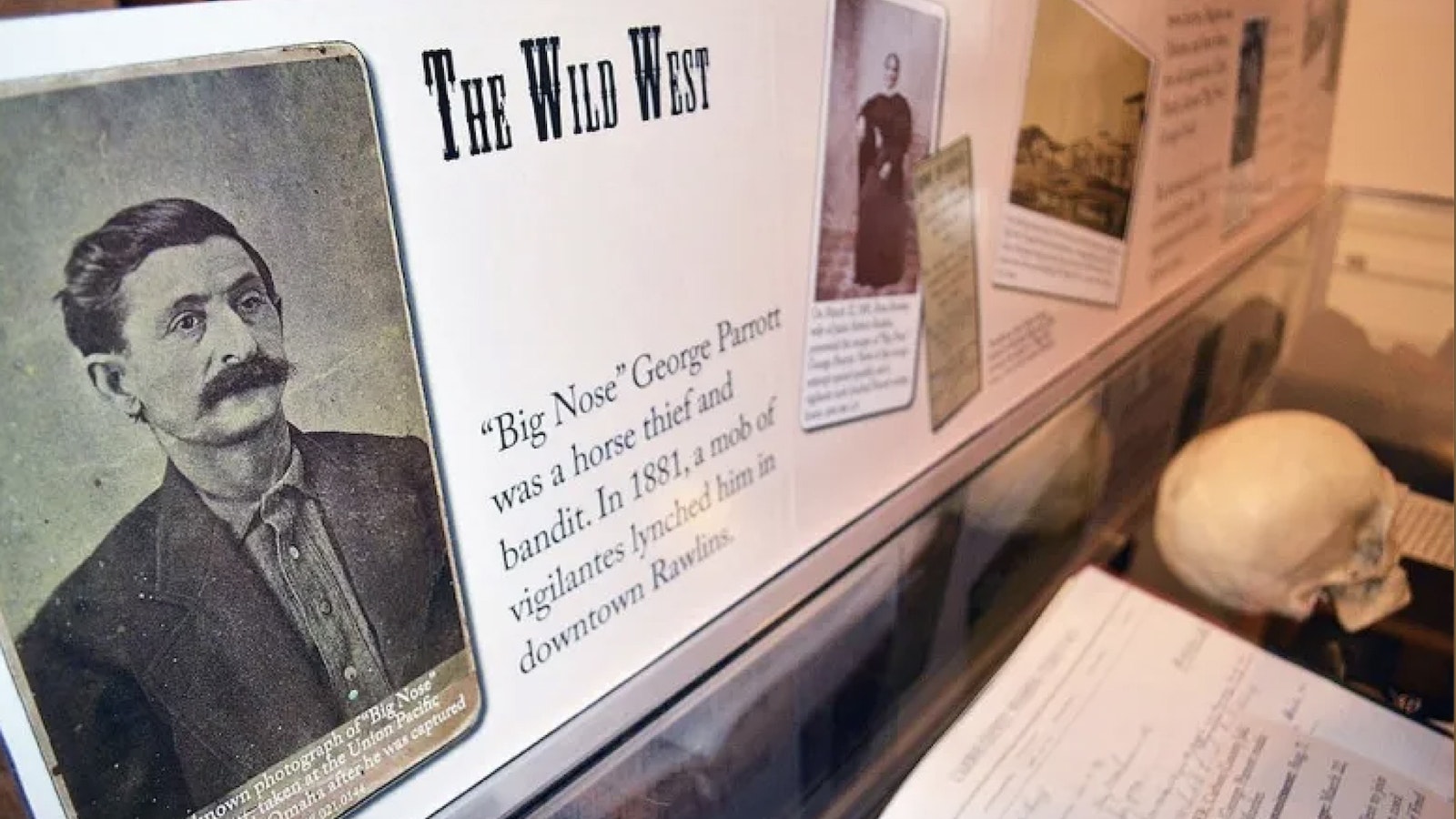

George “Big Nose” Parrott was one such desperado, and he met a gruesome end. His hanging was only the beginning of his punishment.

Parrott was evil personified, what literary types refer to as the antagonist.

In Wyoming, outlaws like Parrott were simply known as “bad guys” and they were strung up quick as God-fearin’ men could find rope and reason.

Parrott was born in Montbéliard, France, in 1834. He arrived in Wyoming Territory in the late 1870s and immediately began robbing stagecoaches with his gang. Eventually, Parrott eyed larger scores — trains — and with bigger reward came bigger risk.

Parrott ended up killing a Union Pacific detective and a local lawman in a robbery gone wrong near Como Lake, midway between Medicine Bow and Hanna, Wyoming. Wanted posters went up everywhere and his capture was inevitable.

One by one his gang members were picked off as a $1,000 reward for Parrott was doubled when he robbed a wealthy Montana merchant, Morris Cahn, in July 1880.

By August, Parrott was arrested in Montana.

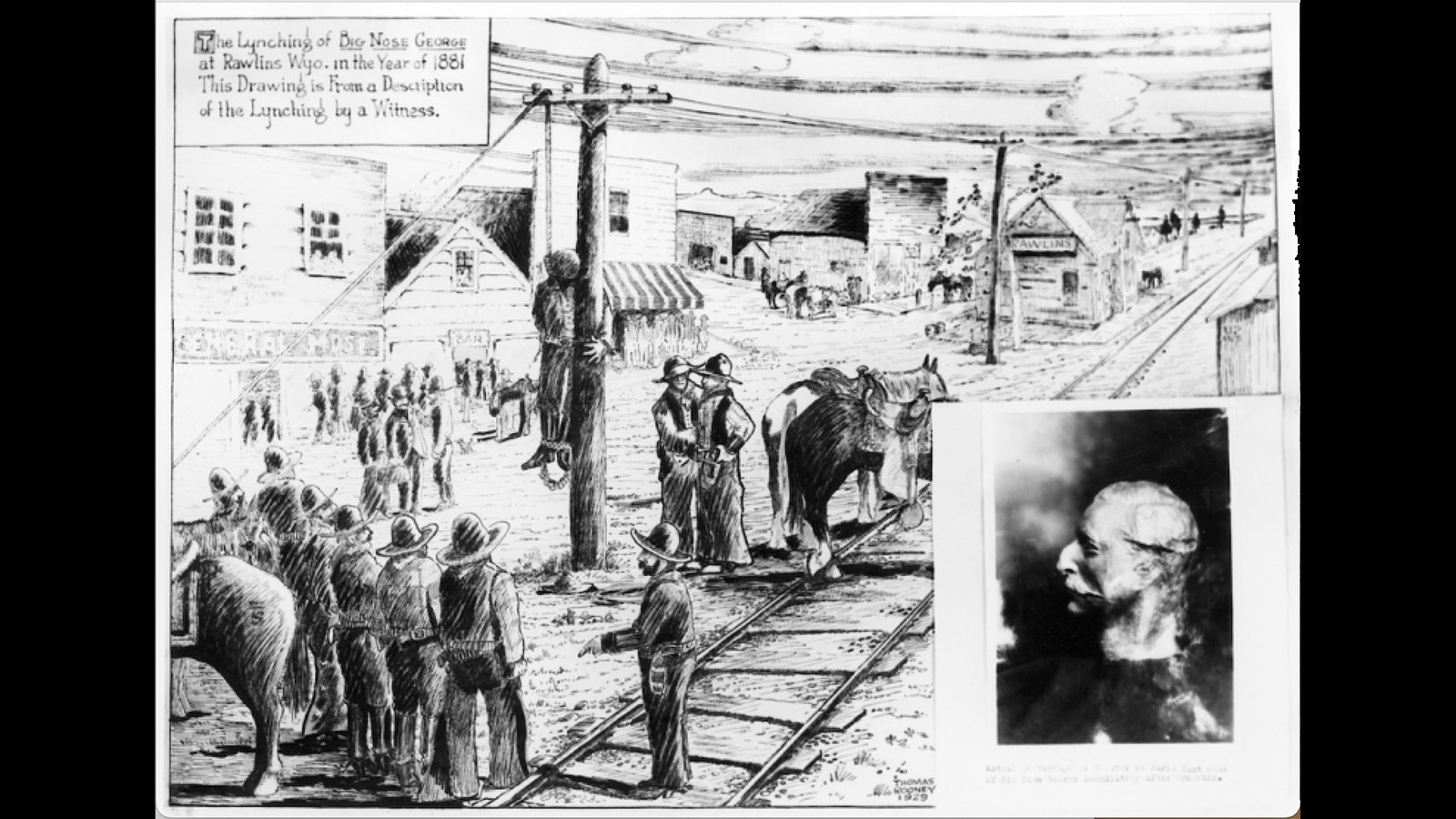

Sheriff Robert Rankin feared angry Wyomingites would be waiting with a necktie party back in Carbon County and, sure enough, despite precautions, a masked posse of about 20 men grabbed Big Nose and drug him to the first telegraph pole they could find.

Up Parrot went by his neck, kicking and struggling. The mob urged the bandit to confess to the killings, promising they would cut him down if he did. Parrott spilled his guts and, true to their word, the angry mob turned him back over to Sheriff Rankin.

Parrott was convicted after a two-day trial and faced hanging. But Big Nose had been plotting his escape and did so, briefly, after jumping the sheriff and his wife Rosa one evening.

He didn’t get far. Townspeople in Rawlins anticipated such a break and surrounded him. This time they weren’t sparing the rope.

Parrott was hung then and there in downtown Rawlins on March 22, 1881, in front of some 200 people who gathered to watch the outlaw swing.

Big Nose Is Parted Out

Dr. John E. Osborne conducted the autopsy along with Dr. Thomas Maghee. They made a plaster of Paris cast of Parrott’s face, cut a large swath of skin from his chest and removed the dead man’s skull cap to examine the brain.

Dr. Maghee gave the skull cap to his 15-year-old assistant, Lillian Heath, who incidentally would go on to become Wyoming’s first female physician. For decades, she used the skull piece as an ashtray, a doorstop and flowerpot.

Dr. Osborne, meanwhile, sent Parrott’s skin to a tannery in Denver with instructions to fashion him a pair of shoes with the dead man’s nipples on each to prove they were footwear made from a human being. He also wanted a doctor’s bag if there was any of George’s skin leftover.

When Osborne received the shoes, he reportedly was miffed that the nipples were not included in the taxidermy. Still, rumor has it, Osborne wore the shoes to his inauguration ball when he was elected governor of the Wyoming in 1893.

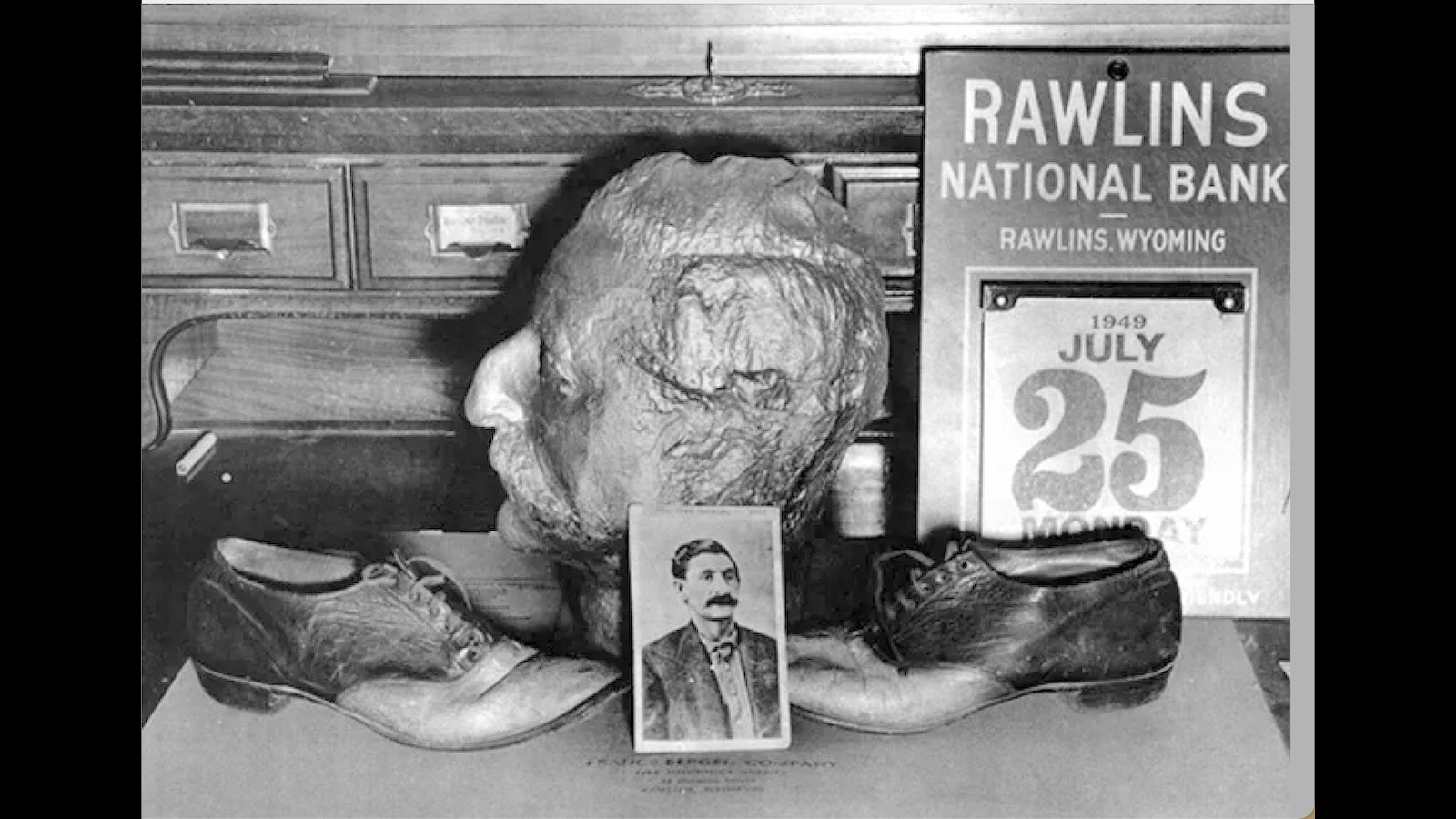

For a time, the shoes, the death mask, a wanted poster and the skull cap were on display at the Rawlins Bank. They are now in the permanent collection of the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins.

The medicine bag made from Big Nose George’s skin has never been found.