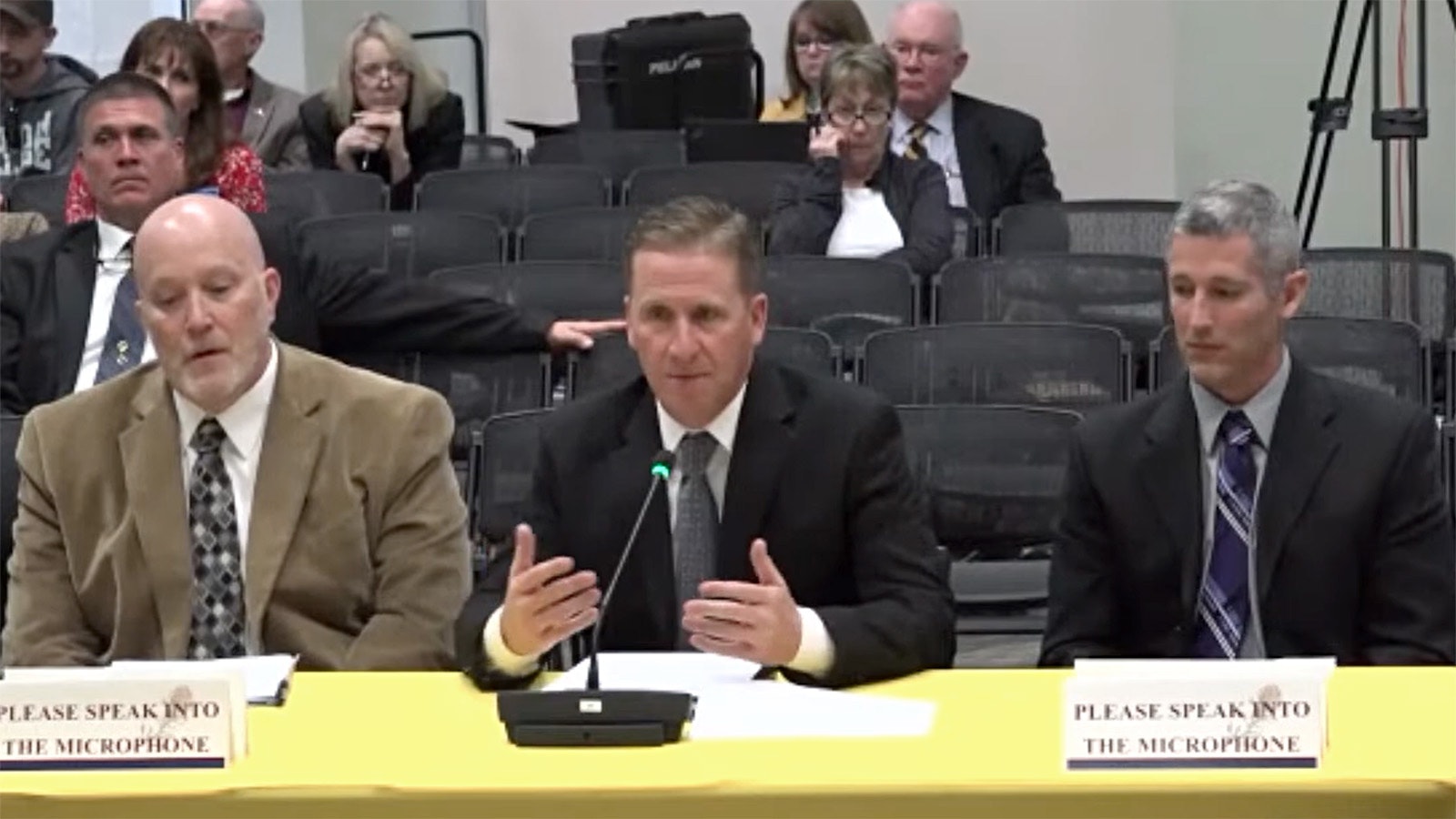

Last year was “an epic year” for officer-involved shootings in Wyoming with 15, more than double the five to seven per year over the previous decade, Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation Commander Matt Waldock told state lawmakers Monday.

A less-obvious side effect of a surge in officer-involved shooting events is the major drain on resources and time they siphon away from investigating other cases, sometimes taking anywhere from one to three months of full-time work to complete.

That includes DCI’s work investigating cold cases from around the state.

“The officer-involved shootings are extremely time consuming, not only for us, but the crime lab, and very draining on local resources as well,” Waldock told the Wyoming Legislature’s Joint Judiciary Committee, which is meeting this week in Sheridan.

Waldock said specifically that the investigation of officer-involved shootings takes time away from working on cold cases.

Cold Success Stories

Since it was founded in 2012, the DCI’s cold case team has participated in or managed 39 cases, including unsolved homicides, missing persons cases and sexual assaults.

This team has solved nine homicides and two sexual assault cases, one involving a serial rapist in Jackson.

In 1992, two unidentified females were found murdered in Wyoming, one discovered near Interstate 90 in Sheridan was named “I-90 Jane Doe.” Another was found a month later off the Bitter Creek pullout on I-80 in rural Sweetwater County. She was nicknamed “Bitter Creek Betty.”

Although Waldoch said local jurisdictions worked those cases hard, they were unsuccessful, and the cases eventually went cold. In 1996, DCI took over the cases when the Wyoming State Crime Laboratory determined the victims were interconnected by the same suspect DNA found on them.

With the collaboration of local agencies and law enforcement in Tennessee and Ohio, authorities were able to locate and arrest a suspect in 2020.

DCI also solved an even older cold case from 1974.

In this case, prosecutors determined Alice Uden shot her third husband Ronald Holtz in the back of the head while he was sleeping, then buried his body in an abandoned mine shaft on the Remount Ranch 26 miles west of Cheyenne.

In 1980, she convinced her new husband, Gerald Uden, to kill his ex-wife and her two sons, who lived in Lander, and dump their bodies into Fremont Lake outside of Pinedale.

Their bodies have never been recovered.

Alice and Gerald, by 2014 an elderly couple, were convicted that year of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Limited Resources

DCI has prioritized cold-case investigations in its general budget since the department was created.

There are 37 DCI agents in Wyoming, seven of which are assigned part-time to the cold-case team. There are14 additional task force members available as needed, including a former FBI agent.

Every member of the team already has ongoing duties they must attend to in addition to the cold-case work. That includes investigating officer-involved shootings from cities and counties around the state.

“They all maintain a full caseload, they’re all expected to handle their normal job duties before they handle their cold cases,” DCI Director Robert Jones said. “They work on these cases when they have time.”

Exhaustive Approach

The cold-case team uses an exhaustive approach to its investigations, studying everything from crime scene evidence to social media records. Sometimes officers also will interview witnesses in other states, a common practice in cold-case investigations.

Waldock said studying genetic genealogy also is an emerging tactic in crime scene investigation, but this method is extremely time consuming and requires advanced expertise.

The cold-case team only meets once every 30-45 days to discuss progress on cases. Waldock said industry best practices have determined a full-time agent should not take on more than five ongoing cold cases at a time.

“As a result of that, these cases take a long time to work,” he said.

Waldock also said there is potential for engaging recently retired law enforcement officers to help with cold cases as reserve agents.

Cold Cases Need Full-Time Attention

But Michael Ciesynski, a retired homicide detective from Seattle and a true crime author, recommended the Judiciary Committee budget for full-time cold-case operatives.

He said having detectives work in any capacity part time is a difficult situation and doesn’t often lead to a great level of commitment.

Waldock said there are very few local agencies in Wyoming that have staff solely focusing on homicide or cold-case investigations. South Dakota has two full-time cold case agents while Colorado has one.

Questions Of Jurisdiction

For the cold case team to open an investigation of its own, it has to be asked by a local jurisdiction handling a case to get involved. Then the DCI team can either facilitate a roundtable with local law enforcement or it can take the case over from the local agency.

But DCI can also open its own investigation at the request of a local district attorney, the attorney general or governor.

Sen. Bill Landen, R-Casper, said this scenario eventually is what happened in a case of suspected abduction in east Casper, but it wasn’t until many years after the original case was opened that DCI got involved.

He said the case remains “a hole in the entire east side of Casper and beyond.”

Are These Mishandled Cases?

Sheridan resident and radio broadcaster Kim Love took a more pointed stance on this case, telling the committee that he thinks law enforcement has mishandled it.

“That family would give anything if you find something out there,” Landen told the DCI officials testifying Monday.

Waldock also told of another Casper case that was not handed over to DCI until 15 years after it had been opened.

Landen expressed doubt that in situations like these that local investigating agencies are actively working these cold cases.

“I’m just curious why we would have cases dating back many, many years?” Landen questioned. “Are they really working those?”

Waldock had no answer.

Jones said his department has to walk a fine line when it comes to the relationships it keeps with local law enforcement.

Thomas Hargrove of the Murder Accountability Project said the relationship the state agency keeps with its local jurisdictions is critical to ensuring a high success rate when it comes to arresting suspects.

Jones said there have been a few instances of local opposition to DCI getting involved in cold cases, but for the most part that’s rare. He said smaller agencies are typically quick to ask for assistance, while the larger jurisdictions with more resources and staff tend to be more possessive.

“There’s no doubt there was some territorial stuff going on, but I’ve never felt like any agency has been opposed to calling us for help,” he said.

One recently popularized cold case that has stayed in local jurisdiction is the 1985 unsolved murder of Shelli Wiley, which was recently documented in The New York Times podcast “The Coldest Case In Laramie.”

Some Good News

Waldock said there’s no statistical algorithm to determine how many missing people in Wyoming have been murdered. He also said there is no tracking mechanism for how many missing people or homicide victims there are in the state.

Hargrove of the Murder Accountability Project had a clearer answer on this question, saying since 1965, authorities have reported 1,006 homicides to the FBI in Wyoming, a rate of 3.3 per 100,000 people. Of these, 856 cases resulted in arrests, a roughly 85% rate, which he said leads the nation.

“Overall, we don’t see much that’s broken in Wyoming based on your clearance rate,” he said.

Hargrove said rural communities tend to have higher apprehension rates because of their tightknit cultures.

On average, Wyoming victims are older, whiter and more female than the national averages. Hargrove said 90% of Cowboy State homicide victims are caucasian, which “is the whitest murder panel I’ve ever seen.”

Native Americans make up 5% of victims, followed by African Americans at 3%. Also, 33% of victims are women, he said, adding that’s 11% higher than the national rate.

But Hargrove said there are also critical gaps missing in Wyoming’s data.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 193 murders in Wyoming from 2010-2019, but the FBI only received reports of 147, a 24% discrepancy. Hargrove said this gap is the fourth highest in the nation.

He suspects some of these gaps are attributed to unreported Native American murders that took place on federal lands, handled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other governmental agencies, which have gone unreported to the FBI.

The Murder Accountability Project is actively pursuing litigation against the FBI to push the agency to report all murders in the United States.