Jen Kocher, Cowboy State Daily

Admitting he had problems was the hardest thing for Michael Watts.

After five tours in Afghanistan as an Army Rangers Special Op, Watts tamped down his battle scars with alcohol and denial. He left the military and returned to Casper in 2014 after five years of service.

Now he’s 34 and a field engineer for a directional drilling company in Casper. On the outside, Watts is a successful guy with a good job and stellar military history. Inside, however, he’s wrestling with his own demons.

When his spiraling drinking problem got serious enough to cost him his marriage and subsequent relationship with a woman he deeply loved, Watts realized it was time to be honest with himself – and others – about what’s really going on.

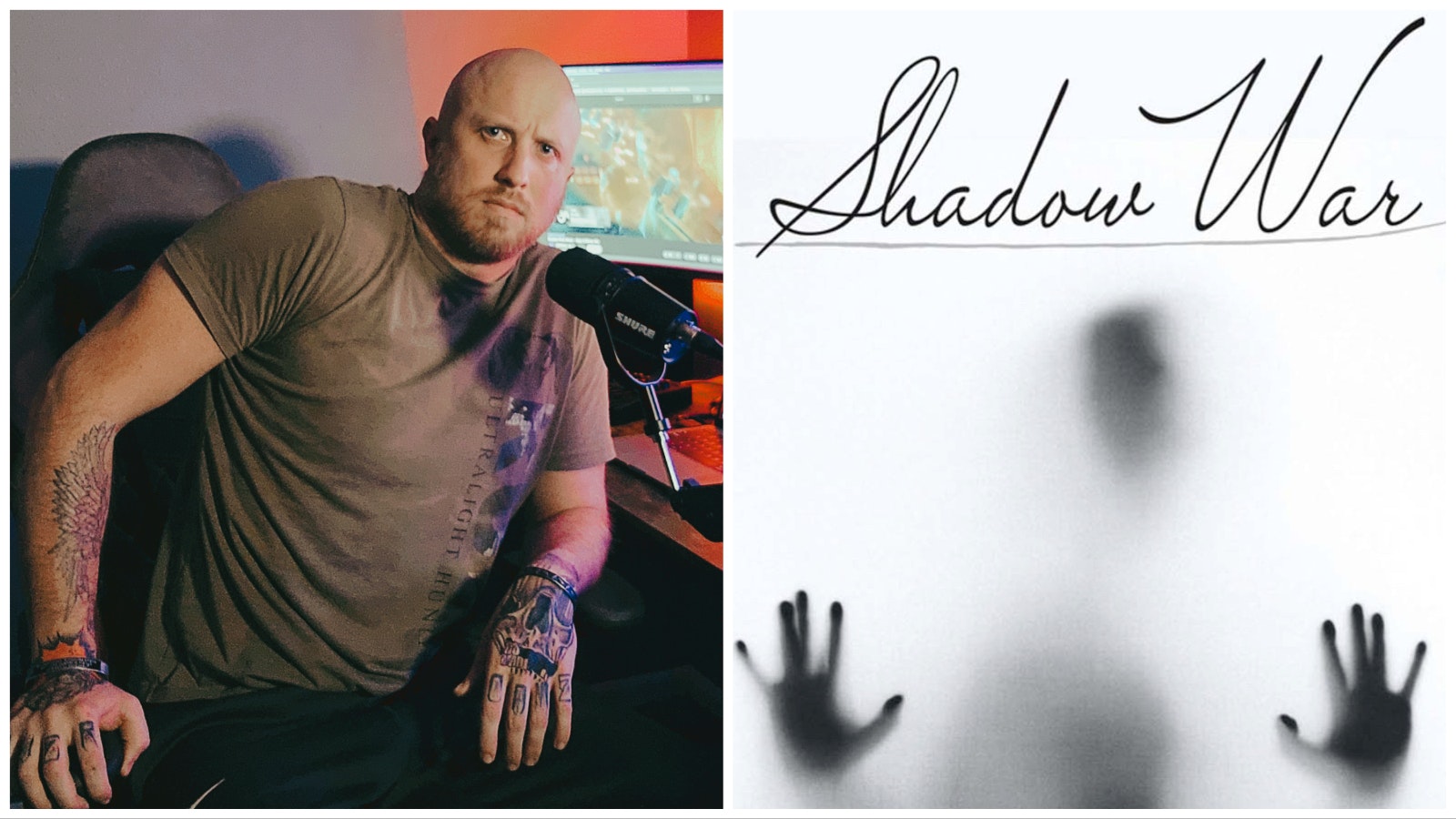

In September, he launched the first episode of his new podcast, “My Life and the Start of the Shadow War,” that has since been downloaded more than 100 times.

Watts told Cowboy State Daily he wasn’t sure what to expect, but realized he struck a nerve with himself and others.

He recently dropped his seventh episode and continues to be surprised by the degree of which this once guarded, and intensely private, special ops Ranger can now speak openly and with raw honesty, often finding himself on the verge of tears as he talks about his own struggles with substance abuse and suicide.

“I’m not ashamed to cry on a public platform because I want people to see that it’s more courageous to actually make yourself vulnerable and say, ‘Hey, I need help,’” Watts said. “Hiding it is not tough. Swallowing your pride and admitting you have problems is much tougher.”

Lawn Dart

Watts joined the Army at age 19. As a boy, the Casper native had wanted to be in the military, but the desire waned in his teens.

He’d initially attended Casper College after graduating from high school, but found himself partying and “letting the college lifestyle” put his scholarships in jeopardy.

“I needed to straighten myself out first,” he said.

Joining the military had been his buddy’s idea. Initially, they wanted to go into the Marines to go to Camp Pendleton, but after seeing a couple guys they didn’t care for in the recruiting line in front of them, they switched course and went over to the Army.

Watts had a cousin who was an Army Ranger, so he thought he’d check that out. He went through the Ranger indoctrination program that Watts described as a “month of hell.” Intense physical training combined with ridiculous time hacks and lots of pushups designed to push you to the limits.

His class started with 350 people. After the first day, that number went down to 150. By the end, he was among a small number to make it into the 75th Ranger Regiment.

After five tours of duty, the physicality of the job took a toll on his body. The Rangers are known for parachuting into danger zones and airfield seizures. At 6 feet, 4 inches and 200 pounds, Watts dropped like a lead balloon. Faster yet since he was a saw gunner loaded down with heavy weaponry.

“I called myself the lawn dart,” he said, adding that once during a training exercise, “I landed on the tarmac and smashed my head.”

He also got his ears rang by lots of bombs. On multiple occasions, they had to drop bombs on enemy combatants at close range. They called it “eating a banger.”

“It rings your ears a little a bit,” he said.

All things told, the physical aftereffects left him with a traumatic brain injury while his experiences in war zones echo in crippling PTSD. The first thing was admitting he had a problem. It wasn’t easy for a guy who had just served his country in harrowing duty as a special op.

‘You Ain’t Right, Son‘

In his podcast, Watts talks about how hard it is to come home after being in the military.

First, there’s the high-octane tempo that he’d become used to serving on the battlefield.

It’s a constant adrenaline rush that makes it hard to return to the mundane civilian world.

There’s also the camaraderie of one’s buddies and being around a bunch of like-minded men on the same mission who are looking out for one another’s lives.

Once home, Watts missed that connection and found it hard to connect to people on the outside. There’s also the memories that Watts and others would just as soon not discuss.

Watts went to work in the oil field but struggled because he didn’t know any other veterans in Casper. This led him to a job at a nonprofit that took veterans from Wyoming and all around the country out on special hunts.

It was on one of these hunts that he met Mike King, who was featured on the third episode of the podcast. King, a retired Green Beret with 23 years of service, saw the telltale warning signs in Watts.

“He said, “You ain’t right, son,’” Watts said.

King suggested Watts had PTSD and traumatic brain injury. This jelled with Watts, who was struggling with memory lapses, a racing heartbeat and inability to sleep, among other issues.

Watts finally called the VA this past year and was diagnosed with PTSD and traumatic brain injury. That was the first step, he said, in admitting he had a problem.

“We don’t want to accept the fact that we do have weaknesses,” he said. “It was definitely a pride thing for me. I knew I was going to feel like less of a man if I ever got checked out.”

Tired Of Seeing Friends Kill Themselves

Watts said his drinking would take longer to get under control.

In his podcast, Watts openly admits to sometimes drinking a fifth a day in an effort to tune out and mask his pain. There were many times he’d driven off the road or passed out in his vehicle. He described coming home from an oil rig, tossing beer cans out the window. Once, he got a DUI.

It got pretty dark there for a while, Watts said. In the first episode, he opens up about his own suicidal inclinations stemming from the dark recesses of his chronic pain.

“Sometimes it just gets old and you just want to get to a point where you don’t hurt and you’re tired of not having that camaraderie that you had in the military,” he said. “There’s been twice in my lifetime that like I straight up racked that slide back … all the meanwhile, I’m holding a bottle in my hand, trying to talk myself into every reason why I shouldn’t do this.”

It always came down to his family, he said. That’s what kept him from pulling the trigger. It was a hard thing for him to admit, he said, and his family was shocked to hear it.

Nonetheless, he came forward because he said he’s sick of the pain and seeing so many of his fellow veterans fall into that same dark place.

“I’m tired of seeing my friends kill themselves,” he said through tears in the first episode of his podcast. “That’s why I wanted to do something like this.”

In his episode “Weight of the World,” he addresses some of the overarching reasons that veterans are particularly vulnerable to taking their own lives.

In the end, his drinking cost him a marriage and his most recent relationship, which he said was his tipping point.

“Shit really hit rock bottom for me,” he said. “I lost someone very special to me. I realized the only way to get better was to do something uncomfortable to make myself grow.”

His goal is to put out an episode each week to continue to reach veterans both in Wyoming and across the country to create a community for all veterans, including females who underwent sexual assault and abuse during their time in the service.

So far, he’s heard from a lot of veterans – mostly in Wyoming – and he’s enjoying talking to them and hearing feedback and learning about other topics they’d like him to discuss on his podcast.

“I’m hoping to speak out for everyone who is too prideful or too afraid to admit they are suffering or need help,” he said.

His goal is to let people know that they’re not alone in the fight and it’s OK, Watts said.

“There’s no shame in needing help and not necessarily being right in the head,” he said. “We all signed up to do a job, and this is just a side effect of the job.”