Editor’s Note: Cowboy State Daily features writer Wendy Corr is traveling across the country as a musician with Cody-based Dan Miller’s Cowboy Music Revue. Wendy will report regularly from the road about people and places within reach of the Cowboy State.

By Wendy Corr, Cowboy State Daily

We all know about the big national parks – Grand Canyon, Arches, Yosemite and, of course, Yellowstone – and our iconic national monuments, such as Devils Tower in northeast Wyoming.

But travelers in the Mountain West would be remiss if they didn’t seek out the unexpected beauty of Colorado National Monument just minutes from downtown Grand Junction, Colorado.

Its colorful sandstone formations, worn away by wind and water, towering pillars and steep canyons are awe-inspiring.

History buffs and thrill-seekers can appreciate the majesty of this spectacular natural formation of cliffs and canyons that was preserved through the singular mission of one man who found his heart in this dramatic landscape of western Colorado.

‘The Heart Of The World’

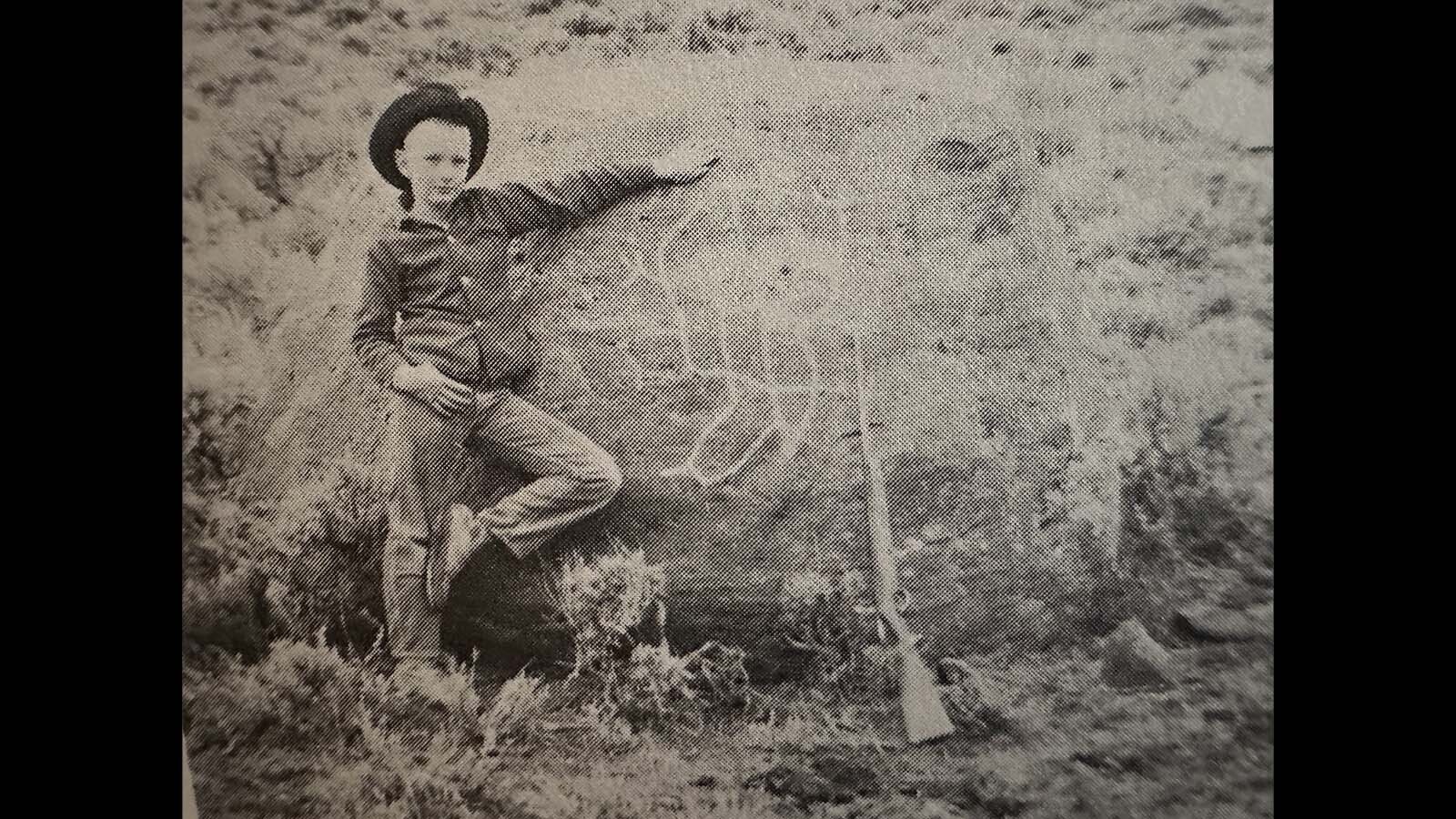

In 1906, 36-year-old John Otto first laid eyes on the rugged canyons and peaks south of Grand Junction.

He wrote soon after that, “I came here last year and found these canyons, and they feel like the heart of the world to me. I’m going to stay and build trails and promote this place, because it should be a national park.”

True to his word, Otto set out to promote the area to locals as well as government officials, and to make the area available to the general public. Prior to Otto’s arrival, many locals believed the canyons to be inaccessible to humans.

According to American conservationist Horace Albright, “Otto was a marvelous guide and knew every inch of his monument, which he tended like a personal kingdom.”

A self-professed trail builder, Otto nearly single-handedly constructed the trails that made the area accessible. He carved a steep stairway up the almost vertical slope of Independence Monument – at 450 feet tall, the most recognizable feature in the park.

Otto named the rock formations after people and historical events in American history.

“At the beginning of my work it was agreed to name everything out of United States history as much as possible, leaving out Biblical, foreign, and fictitious names,” he wrote.

Lobbying for National Park Status

As Otto continued to build trails and invite residents to explore the area, the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce sent a delegation to observe his work. Upon their return, the group praised Otto’s efforts and the scenic beauty of the area.

Otto’s plans to make the area into a national park included invitations to the very top levels of government. Both Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft received invitations from Otto, although they went unanswered for a time.

By 1909, the local newspaper joined Otto in lobbying to make the area a national park, and eventually Taft did visit Grand Junction for the peach festival that year.

But by 1910, no movement had been made on the matter, so Otto and other supporters of the effort deluged Washington politicians with letters.

While a bill was introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives and passed into the Senate, roadblocks came up in the congressional process in the final months. President Taft stepped in and invoked the Antiquities Act, making a presidential proclamation designating the canyons as the Colorado National Monument.

The proclamation was signed May 24, 1911, and Otto was hired as the park’s first ranger, drawing a salary of $1 per month (around $33 in today’s dollars).

Otto continued in that role for the next 16 years, living in a tent in the park and building and maintaining trails until leaving the post in 1929.

Independence Day Tradition

Otto’s influence on the region is celebrated every year in an annual flag-raising at the top of the 450-foot-tall Independence Monument.

Otto worked day after day for weeks in 1911, carving out footsteps and pounding iron pipes into the solid rock at the only possible approach to the pinnacle of the monolith so that any one brave enough to climb that far could ascend to the top.

After his first successful attempt to reach the plateau at the top of Independence Monument on June 8, 1911, Otto raised an American flag at the top – and every year since the tradition has continued on the Fourth of July.

Even now, more than a century later, visitors from around the world still flock to the national monument to witness the flight of the flag on Independence Day. Today, though, it is the Mesa County Technical Rescue Team that raises it.

Worth the Trip

The park is home to a number of species of wildlife, including golden eagles and red-tailed hawks, bighorn sheep and coyotes. From 1925-83, a herd of bison called the monument home, as did a small herd of elk.

But the views are what draws people to the Colorado National Monument.

Few are as impressive as standing at the top of “Cold Shivers Point,” a precipice overlooking steep canyons that cast tall shadows over the city of Grand Junction.

No matter the season, the Colorado National Monument is a worthwhile and memorable stop along the Western Slope of the Centennial State.