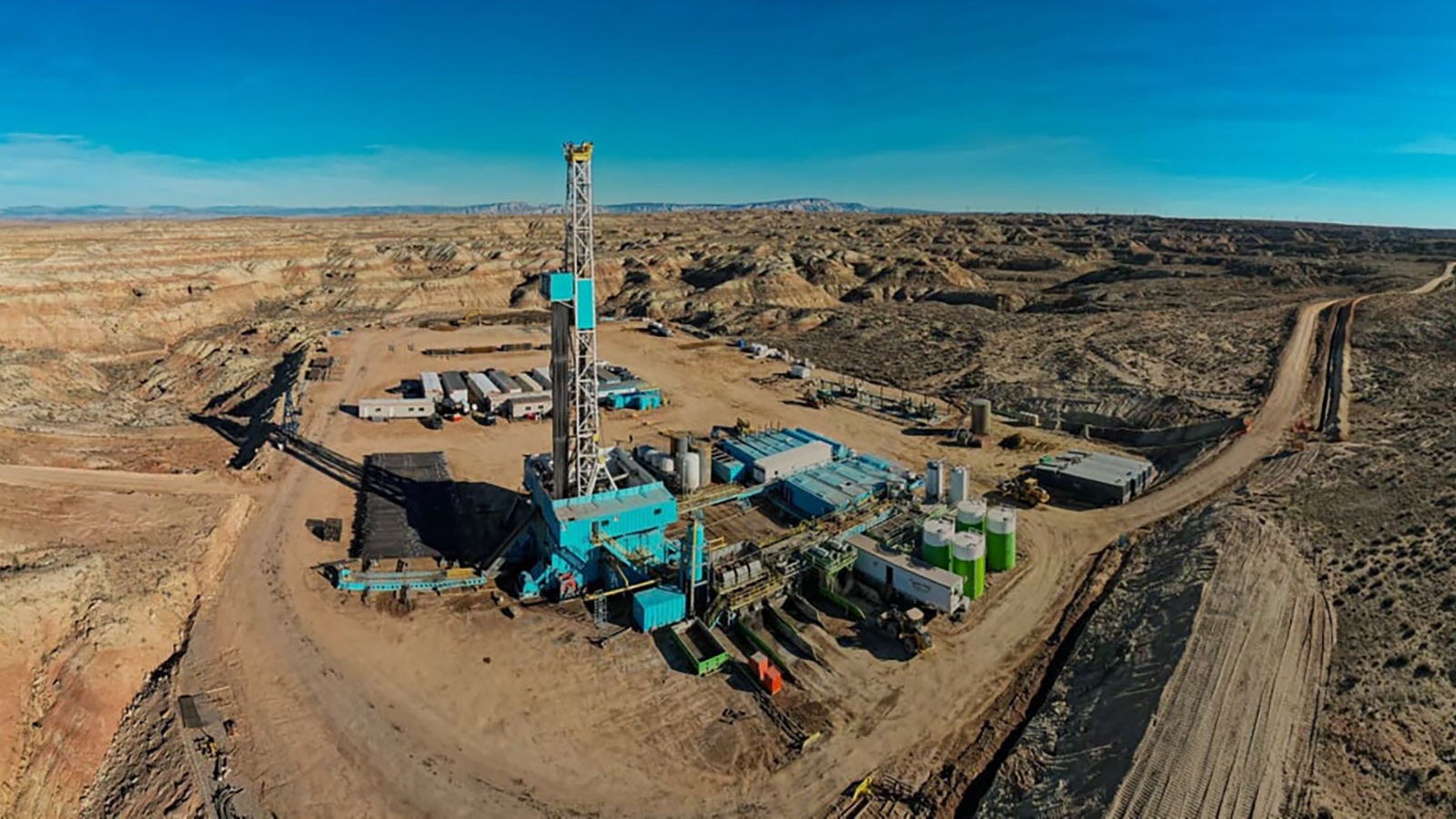

The “Shale Revolution” describes America’s rise as an energy leader beginning in 2010. Thanks to technology developments involving hydraulic fracturing, huge volumes of oil and natural gas were unleashed onto the market.

“It was such heady days that there was some spending like drunken sailors. U.S. oil and gas production grew just crazy fast,” Chris Wright, CEO of Liberty Energy Inc., told Cowboy State Daily.

After the busts sobered the industry, companies aren’t sending out hundreds of fleets of frac crews to drill across America. In Wyoming, the rig counts grew and fell, and now companies here have cooled with a different mindset that no longer hungers for another boom.

Healthier Industry

There are a number of challenges facing the oil industry.

Cratering demand during the COVID-19 pandemic has been short but jarring. The election of President Joe Biden ushered in an administration that’s openly hostile to fossil fuels. The sweetest spots in the major oil and gas producing areas have been drilled and contracted, and investment capital is harder to come by thanks to the environment, social and governance (ESG) movement.

While it may appear the Shale Revolution is done, experts in the industry say what really happened is that the industry has matured.

“Our competitors and our customers are investing at a disciplined pace to keep capacity roughly flat or only very modestly growing. That’s a healthier state for our industry,” Wright said.

More Efficient

Paul Hladky, vice president of Gillette-based Cyclone Drilling, told Cowboy State Daily that after booms and busts, investors are looking for shorter-term results with more certainty. He said it’s a much more careful and efficient industry.

“This is the first time in 25 years I’ve been here that we’re not in construction mode,” Hladky said. “And we haven’t been in construction mode since 2020.”

Hladky said large oil companies are providing a return on investment. These past few years have been very profitable for all of them, and their cash flow is strong.

“They’re making money right now for their investors, and they’re paying dividends,” Hladky said.

But it’s no longer all about growing production. Now the industry does a lot more with a lot less.

“I tell people that all the time,” he said. “We get better. We use data and analytics to guide us in our decision making. It’s very methodical and thought out, and it’s never been more productive or more efficient.”

Oversupply

Wright said there was much celebration when U.S. oil and gas production grew so much in such a short period of time. What other oil-producing nations did in 30 years using conventional techniques, America’s Shale Revolution did in a single decade.

The world was awash in energy.

“It turned out, it was mostly great for the world but not great for the shale industry,” Wright said.

The focus on production led to an oversupply and investors started to see the industry as a destroyer of capital.

“If you look in the rearview mirror, it was true,” Wright said.

Liberty Energy took a different approach, Wright explained. It’s experienced the cycles as the rest of the industry, but has had a 23% cash return on capital invested since the day the company started in 2011.

Sweet Spots

Geology also is presenting a challenge for the industry.

In the early days of the boom, there were a lot of untapped shale deposits and tight sand formations bursting with oil and natural gas. Those sweet spots were the first to get drilled, and now operators are having to look a bit harder to find the product.

Paul Ulrich, vice-president of government and regulatory affairs for Jonah Energy LLC, said it’s a problem, but technology is improving parallel to that challenge.

“It never ceases to amaze me what we can do on the technology front to access more rock and better rock more efficiently,” Ulrich said.

Hladky said that Wyoming’s Powder River Basin didn’t see the kind of development that Texas’ Permian Basin or North Dakota’s Bakken saw during the boom years because the economics of the play aren’t as good.

But with better, more efficient technologies, Wyoming retains a lot of potential and the economics are improving, he said.

“Yes, some of the more-sweet spots are taken and leased up, and maybe even drilled out. But there’s still a lot of opportunity,” Hladky said.

Wright said there’s a line between the tier one spots and the tier two areas, and the industry is probably crossing that line. But as Ulrich and Hladky pointed out, technological improvements in fracking are offsetting geological challenges and creating a much more gradual decline.

It’s not the end of fracking, though.

“Yes, that is a factor as well, but it’s not, ‘Oh all the good shit is done.’ It’s much more gradual,” Wright said.

Wary Workers

Besides creating reluctance for investors, the recklessness of the boom years also made workers reluctant to pursue careers in an industry that might lay them off every few years. Without that certainty to offer workers, many oil and gas companies are struggling to recruit, even though they pay well.

Hladky said that Cyclone Drilling always has been careful not to fall into the cycle of bringing people in and tossing them away when the cycle hits a downturn.

“For Cyclone Drilling to do well, our people need to do well,” he said. “It’s thought about in every decision we make. We want to provide a good workplace for employees.”

He said it helps that Cyclone is a private company and doesn’t have shareholders to appease. This allows it to maintain the company’s workforce when times were slow.

Tightened Belts

Wright said in the Rocky Mountain region, between the fourth quarter of 2014 and the second quarter of 2016, activity in the industry declined by 70%. That meant around a third of the workforce was laid off.

“That’s brutal,” Wright said.

During that period, Liberty had about 600 employees, and ended it with about 600 employees. The bonuses were lighter and perks went away, but there were no layoffs, Wright said.

“Everyone worried about their jobs and where they were going. It was an incredibly stressful time,” he said.

Liberty’s employees, meanwhile, watched their friends at other companies losing their jobs right and left.

“Absolutely, that makes us a less attractive industry to work in,” Wright said.

Oil Field Proud

It also doesn’t help that there’s a nonstop message that the oil industry is destroying the world, Wright added.

Unlike many other companies, Liberty Oil doesn’t apologize for producing energy that provides enormous benefits. The company’s ESG report, called “Bettering Human Lives,” doesn’t shy from the environmental impacts of oil, but it presents them in a context that considers the benefits of the industry.

“It’s simply not possible to discuss the environmental and social impacts of our industry without considering the environmental and human impacts of the absence of our industry,” the openining paragraph of the report reads.

Wright said the company mails copies of the report to all their employees so they can be proud of the work they do.

“You’ve got a nonstop drum from politicians talking about oil and gas destroying the world. That makes it harder to hire people, and it’s another incremental factor making it a little bit tougher for us to grow U.S. production,” Wright said.