In a home in central Wyoming, a pre-teen girl worries that she’ll be taken from her mother because of her heritage.

The girl has been cared for by a guardian for most of her life and thinks of her guardians as mom and dad. But she is American Indian, while her guardians are non-native.

A federal law, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) mandates that the girl’s guardian family should be her last-resort caretakers because they are not Indian tribal members. And if a custody dispute arises, the girl’s tribe can place her back with her biological parents or in another tribal home – regardless of how attached she is to her guardians.

‘Why Can’t I Be Adopted?’

The girl’s guardian, who thinks of herself as her mother, shared her story with Cowboy State Daily on Monday, but asked to be identified by the alias “Ashley” for fear of reprisals.

Ashley is a foster mom and has adopted some of her foster children. But she cannot adopt the native child who has been in her care for years because the tribe to which the child belongs does not traditionally terminate parental rights, Ashley said.

Ashley said it’s heartbreaking to explain to her native daughter why she can’t be adopted but her siblings have been.

Guardianship is similar to adoption, but it’s not permanent and can be challenged or revoked.

“My daughter will often ask me, ‘Why can’t I be adopted? Is it because of the color of my skin?’” Ashley said.

The answer doesn’t come any easier than the question.

“I have to tell her, ‘No. It’s actually because of the color of my skin, and because I’m not an enrolled member of a tribe,’” Ashley said, adding that the girl doesn’t always understand the reach of the law over her life.

“Because to her, I’m her mom, and I’m her family, and this is her family and she’d love to be formally adopted,” she said.

Ashley believes that if a Wyoming state court had sole jurisdiction over the girl’s case – if it were not an ICWA case – the biological parents’ rights would have been terminated and she and her husband could have adopted the girl.

“Without question,” she said.

Boarding School Horrors

Ashley said she understands why the Indian Child Welfare Act was written in 1978. Americans were waking up to atrocities committed in boarding schools designed to assimilate native children to white culture.

By the 1920s, harsh and violent punishment and sexual abuse were rampant in many boarding schools, according to researcher Dr. Jane Palmer.

So, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act. The law gives tribes intervenor rights over native children in custody cases that originate off reservation lands, while keeping on-reservation custody cases in tribal court. It aimed to protect tribes’ sovereignty and preserve their culture by keeping Indian children in the tribe.

ICWA directs courts overseeing Indian-child cases to foster a child with a family member first, then with a member of that child’s tribe if no family member can be found – then with a member of any American Indian tribe.

Non-native families are the child’s last resort for placement under the ICWA law.

Ashley said she empathizes with the desire to keep tribal children near and preserve tribal culture through them, adding that her family celebrates her daughter’s culture with her frequently to honor that value.

But Ashley also said she wishes the best interests of children and relational attachments are prioritized before their racial heritage.

“My home is not a boarding school,” she said.

Wyoming Working On Its Own ICWA

The U.S. Supreme Court is contemplating the possible overturn of the Indian Child Welfare Act, which has been identified in other cases as having constitutional issues. That case could be decided by June.

Some Wyoming lawmakers now are trying to codify a state version of the act to keep it in place if the high court overturns the federal version of it.

They also are working to pass a bill that could help reform the state’s version of the law to address what many foster families see as an imbalance that disfavors children.

Senate File 94, which would codify ICWA as a state law, cleared the state Senate on Tuesday morning and is headed to the House.

House Bill 19, which would make an ICWA task force, is being contemplated on the House floor this week.

‘Denied Their Right To Permanency’

Other foster moms raised concerns to Cowboy State Daily about the possibility of the state continuing ICWA. Cowboy State Daily has verified their identities but has honored their requests to remain anonymous because of their fears of reprisals for speaking out.

A foster mom who chose the alias Justine told Cowboy State Daily she believes ICWA is unconstitutional and racially discriminatory against the very children it was designed to protect.

“The permanency for those children (is what) they desperately need – any child no matter what color that child is has a desperate need for permanency,” said Justine. “Native American children are denied their right to permanency because they’re Native American – and that is unconstitutional.”

Justine said she, too, is anxious at the prospect of losing her Native children in guardianship “if a suitable Native American family comes along.”

It’s happened to her before.

Justine said it’s hard on the children.

“We are no longer having the Catholic schools coming and taking children out of the home and putting them in boarding schools,” said Justine. “We are no longer having white people shopping the reservation for children. That’s not how this happens.”

The Stories

Justine said she’s seen her foster children placed back in extremely abusive homes that they otherwise would not have been placed in because of the ICWA. If tribal termination criteria for parental rights were aligned with the state’s termination standards, she said the kids would not have been put back in terrible situations.

The stories Justine told involved physical abuse, child rape and drug exposure, but they could not be retold in a way that would preserve her anonymity.

ICWA Also Used To Save Child

A mother who chose the alias LeAnne said she has native children in guardianship. While she hasn’t had any court disputes over her children, like Ashley and Justine, she worries that she could lose the children if a tribal family asks to take them.

“We can be dragged into court at any time,” she said.

On the other hand, said LeAnne, she’s seen ICWA work to benefit a child.

She talked about an instance where a child’s tribe intervened to remove native children from a bad non-native foster family situation.

LeAnne said she’d like to see parts of ICWA codified in state law, but with tethers ensuring that tribal Departments of Family Services are accountable to the state for how they use state DFS money.

Wyoming allocates nearly $1.5 million in state funds each biennium to the Eastern Shoshone Tribal DFS and about $4.4 million to the Northern Arapaho Tribal DFS, according to Wyoming DFS Director Korin Schmidt.

‘Thankful For What We Do Have’

There was a case in Wyoming’s tribal court on the Wind River Indian Reservation in which a tribe agreed to terminate parental rights after the parents insisted their rights be terminated, Ashley said.

But that’s an extreme rarity, she said.

Ashley has considered asking her daughter’s biological parents to agree to terminate their rights, but she’s scared that asking that question would provoke them to act against the family.

“I personally have never approached the parents about this because of fear that they would … try to get the kids taken away from us just for asking,” said Ashley. “I just try not to make a big fuss about anything and just be thankful for what we do have.”

Although ICWA was made to combat racial discrimination, it’s become a new form of discrimination because of permanency problems like these, Ashley said.

She said her daughter is “being discriminated against because (she’s an) enrolled tribal member. How do I explain to her … ‘I’m sorry, I’d love to adopt you, but I can’t because you’re an enrolled tribal member and I’m not?’”

Smooth Sailing For State ICWA, So Far

Sen. Affie Ellis, R-Cheyenne, sponsored SF 94 to codify ICWA. The bill passed the state Senate on Tuesday with a third-reading vote of 20 in favor and 11 against. It’s now is being considered by the House.

Ellis told Cowboy State Daily that making a state ICWA law merely preserves the status quo by keeping in place the federal law Wyoming’s courts have adhered to for 45 years.

She also emphasized the horrors ICWA was written to address. Ellis, a member of the Navajo nation, had told a legislative committee last week that her mother was abused in an assimilative boarding school.

Ellis said though its objective is cultural preservation, the law still has requirements designed to protect children.

“If a child’s health and safety is in danger there are processes that need to be implemented to make sure they’re not maintained in those unsafe environments,” she said. “However, if the children are domiciled on the reservation it is tribal DFS (systems) that have some of those responsibilities.”

Ellis described SF 94 as a “stopgap” to keep the status quo in place so that the state’s ICWA contracts with tribal DFS systems don’t spark court challenges if the federal law is overturned.

She said she empathizes with the concerns of foster mothers about native children not having as much permanency and therefore being vulnerable to abuse, and believes that HB 19, the task force bill, could be an avenue to reform the state ICWA in the future with tribal input.

She does not know what those reforms might look like, Ellis said.

“There’s always concern from the tribal perspective about any effort that might erode ICWA so I’d caution against anyone coming in with any preconceived notions about how those conversations should start,” Ellis said. “That should be left to form organically, if we get that taskforce passed.”

While both the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes of Wyoming support SF 94, to codify ICWA immediately, only the Northern Arapaho tribe supports HB 19, according to tribal leaders’ legislative testimonies.

Native Families Should Be Given The Choice

Another foster mom who chose the alias Ester said she dreads the idea of ICWA being adopted as a state law, because she’s seen kids abused after being returned to parents who, under a state court, likely wouldn’t have their parental rights anymore.

But if the Legislature does pass a state ICWA, Ester said she’d like to see it amended to let biological parents who live off a reservation decide if they want their tribes involved in their children’s custody cases.

Ester has fostered children whose biological parents had left the reservation to live elsewhere and who didn’t want to see their children taken back to it.

“In the real world where I currently live, parents do have a choice and parents can choose if it’s not safe or they don’t feel the foster parents are caring well – they can ask for the children to be moved,” said Ester.

But tribal families can’t cut their tribes out under ICWA, she said, adding that, “I feel that native families (should be) given the choice.”

All Of Wyoming Impacted By Crime, Poverty

The Eastern Shoshone tribal government did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

The Northern Arapaho Tribal government said in a statement that the ICWA should be codified to help stop “the decades-long practice of Native children being ripped from their families and placed in non-Native homes or boarding schools in order to erase their Tribal identify and heritage.”

Tribal courts and tribes do consider children’s best interests in custody cases, the tribe said.

“Contrary to the claims of ICWA opponents, the best interests of every Native child are considered on a case-by-case basis under the current system,” the statement reads.

The tribe also cautioned against assumptions that the reservation’s widespread poverty, high rates of substance abuse and other socioeconomic issues are exclusive to it.

“Issues of substance abuse, poverty and more are not unique to Indian Country – they are a national crisis that afflicts every corner of Wyoming,” the tribal government wrote. “To claim otherwise is not only false, it is offensive and an echo of the assimilationist arguments of the 1800s and 1900s that Native children needed to be removed from their families and community for their own good.”

Northern Arapaho Business Council member Karen Returns To War testified before a state legislative committee last week, saying that three of her siblings gave children up for adoption and that her sisters were coerced into doing so by a federal government official in the 1970s.

The federal policy of the time was one of assimilation. Her older sister’s niece was raised by one German parent and one parent of unknown ethnicity in Alaska, she said.

That niece has since found her way back to the reservation and has bonded with the family, Returns To War added.

“She said she’s really glad she found us,” said Returns To War. “Because she never experienced the love she’s been getting; the family support and unconditional love.”

Returns To War said her other siblings haven’t reconnected with their children, adding that her sisters regretted giving their kids up for adoption.

“They wondered where their children were, and were they safe,” said Returns To War, noting that the women also hoped their children had connected with their tribal traditions and heritage somehow.

Poor Does Not Equal Dangerous

Ellis said Wyomingites shouldn’t get into the habit of thinking that a well-off foster family would be necessarily better for a Native child than his or her impoverished family.

Responding to stories of sexual and physical violence against children due to foster permanency issues, Ellis said these stories reaffirm the need for child services departments and others to discuss the issues in the proposed task force.

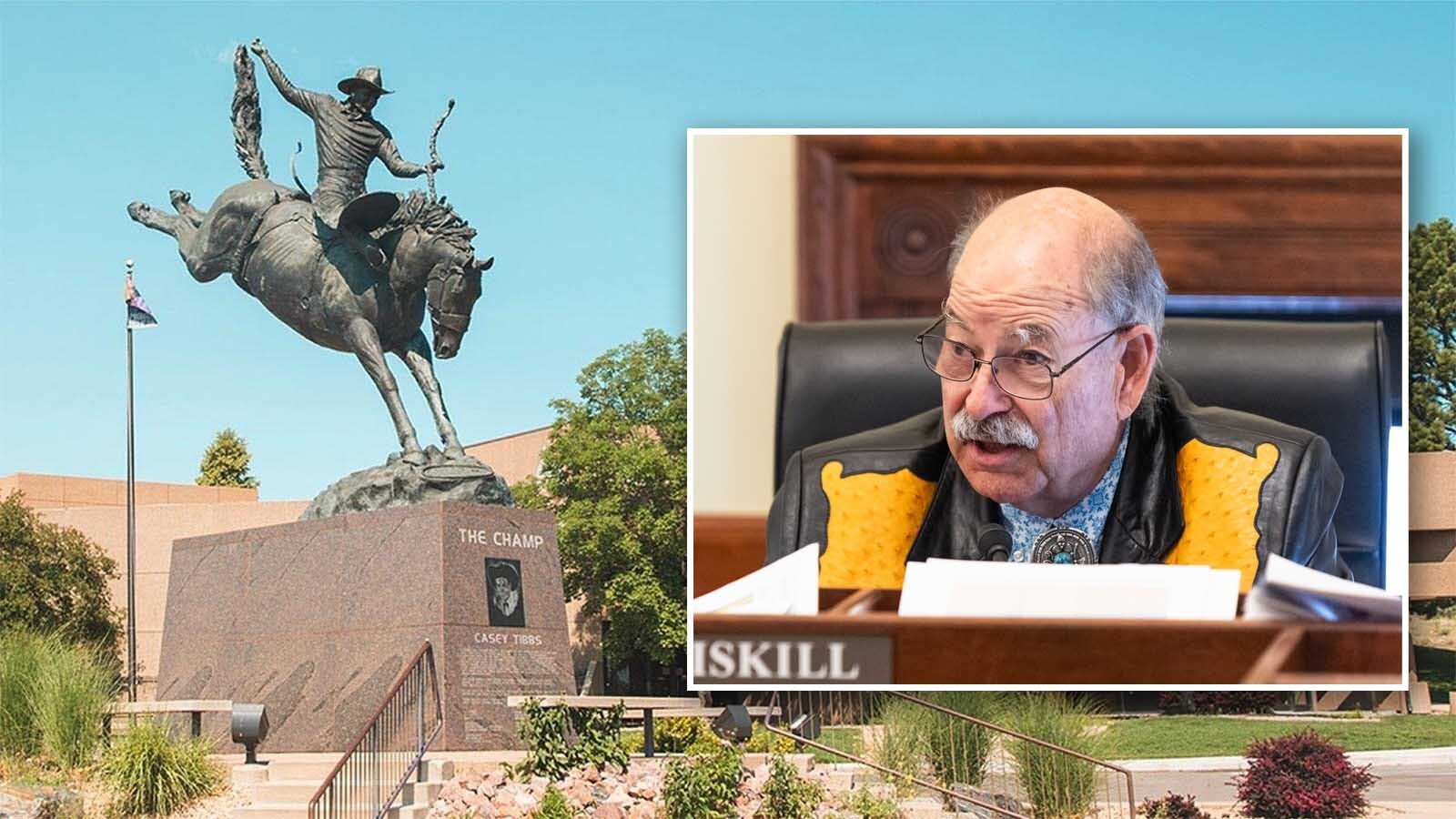

Rep. Lloyd Larsen, R-Lander, co-chairs the legislative Tribal Relations Committee with Ellis and is a key proponent of the task force bill.

Larsen told Cowboy State Daily that while many non-native guardian families are rejoicing at the thought of ICWA being overturned, many native families dread the thought.

“You hear the concerns from tribal members and families across the nation that are crying out and saying, ‘Are we going to revert back to pre-ICWA days when 80% of every (Native) home had one child taken out and placed somewhere else?’” said Larsen.

Larsen said it is a tricky balance, trying to preserve tribal cultures while addressing children’s best interests, but in carrying the bill he hopes to prevent “the pendulum from swinging the other way,” back to forced assimilation.

Political Class, Not Just Race

Larsen in legislative presentations has highlighted the federal government’s position on ICWA in the Supreme Court case against it: that it’s not racial discrimination, but is an inter-governmental law.

The ICWA language treats American Indian children as members of a political class, not merely a race.

The federal government argued before the Supreme Court on Nov. 9 that Congress has the right to deal with off-reservation Indian children as subjects of a “lesser sovereign” – the tribes.

Congress historically has regulated Indian tribes as lesser sovereigns. Should the Supreme Court declare that ICWA is racially discriminatory, the court could upend volumes of Indian law along with it.

The foster families challenging ICWA argued that the law treats native children living off the reservation as a tribal “resource” and “possession.”

Having passed the Senate, SF 94 reached the state House of Representatives on Tuesday but has not yet been assigned to a committee. HB 19 was placed on the House general file Wednesday, but will have to get through both the House and Senate to become law.