When Mark Caughlan took over as chief ranger for Wyoming State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails, he began scheduling trainings for rangers across the Cowboy State.

One of those sessions – for ice water rescues – became even more relevant in the wake of a tragic rescue response at Keyhole Reservoir in December that claimed the lives of three people.

Trapped Under The Ice

On Dec. 15, two people died attempting to rescue a man who fell through the ice at Keyhole Reservoir in Crook County.

“There were two people in the cab of the UTV (Utility Terrain Vehicle), and there was a guy in the back of the UTV – we’d call it like the truck bed of the UTV,” Caughlan told Cowboy State Daily.

The vehicle plunged into the icy reservoir, he said.

“So, when they drove off the edge of the ice shelf, the two people in the cab couldn’t get out, and they’re the ones who drowned,” Caughlan said. “But the guy in the back was actually able to self rescue, get himself to the edge of the ice and get himself out.”

The tragic situation was the lens through which park rangers from around the state viewed training less than a month after the Keyhole Reservoir incident – one that could help mitigate future incidents and save lives.

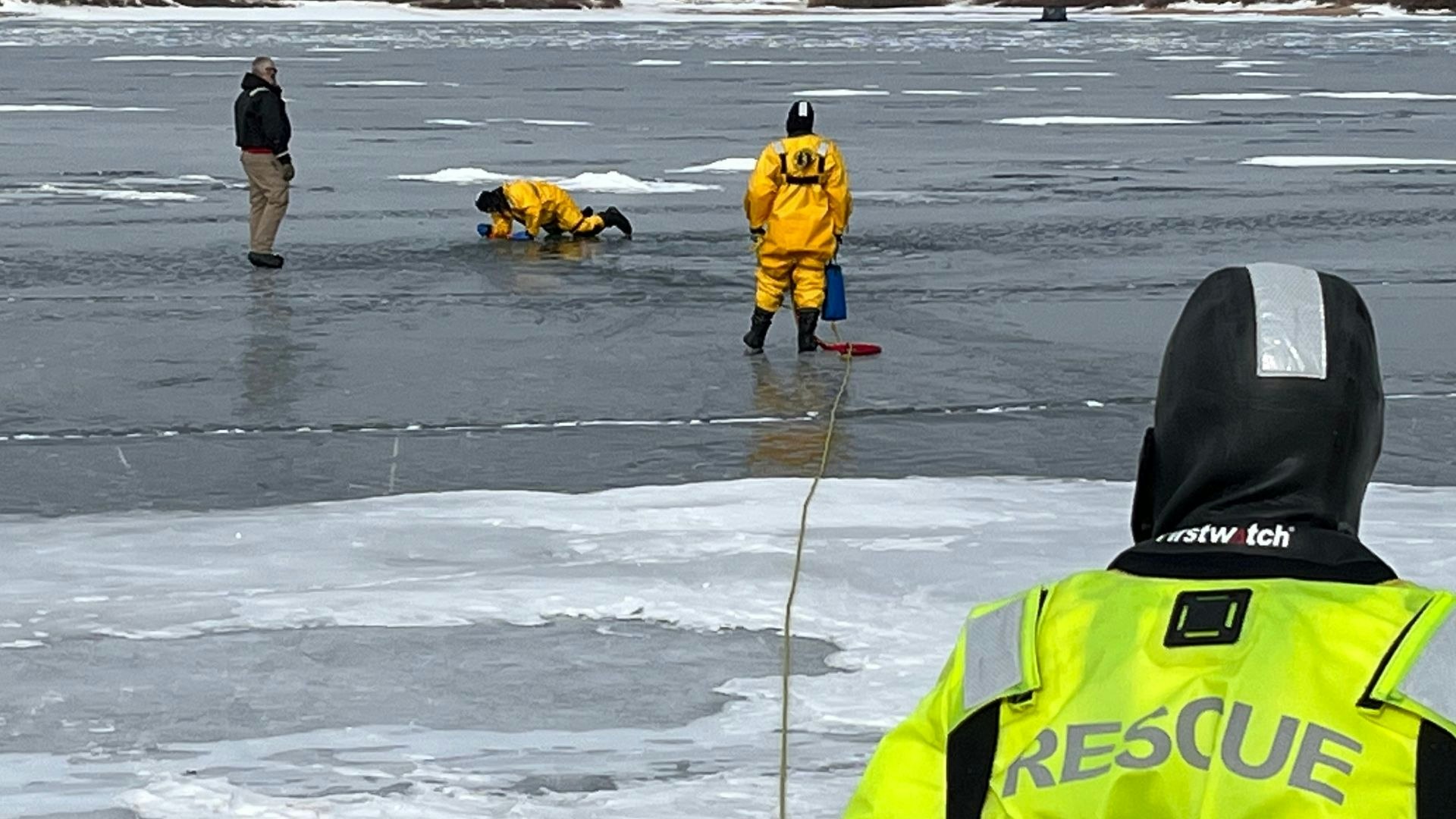

Multi-Agency Training

Caughlan said rangers from a number of Wyoming state parks – including Keyhole, Boysen, Curt Gowdy, Guernsey and Seminoe, as well as an officer from the Laramie Game and Fish office – participated in an ice rescue training he’d put on the schedule just a week prior to the tragedy at Keyhole.

“One of my jobs as chief ranger is to provide the appropriate training that our field staff need to provide the best visitor safety, and for safety for our rangers,” said Caughlan, who spent 27 years with the Larimer County natural resource agency in Colorado. “One need that I identified was ice rescue training.”

The training was held Jan. 5-6 at Curt Gowdy State Park and included professionals from Dive Rescue International, a company based in Fort Collins, Colorado.

“They’re one of the best training organizations in this particular training – in ice rescue – in the country,” said Caughlan. “They teach the FBI, they teach dive rescue, they do a lot of different things.”

Details Matter

Caughlan said the session covered a broad range of issues.

“The first part is understanding ice conditions – how ice forms, how it develops, good ice versus bad ice, what thicknesses of ice could hold different weights, how to identify fissures and hazards in the ice,” he said. “And then, obviously, the equipment you need and how you would go about rescuing somebody that went through the ice – the equipment, the experience, how you would go about solving that problem.”

Professionals At Work

Park rangers wear many hats requiring a wide range of training, Caughlin said.

“We do law enforcement, we do education interpretation, we do search and rescue and respond to medical emergencies,” he said. “We do light maintenance. We do horse patrol, mountain bike patrol, boat patrol.

“And ice rescue and swiftwater rescue and low-angle rescues are all part of that. Those are things that we’re adding to our training criteria.”

A park ranger’s main job, according to Caughlan, is to solve problems.

“Whether it’s a funding problem, someone fell through the ice problem, there’s a forest fire problem, someone got bit by a rattlesnake problem: Whatever it may be, our job as a ranger a lot of times is just solving problems,” he said. “How do we solve this particular problem? And how do we do it safely?”

No Amount of Training

But no amount of ice rescue training could have helped the men who died Dec. 15 at Keyhole Reservoir.

“Typically, when you break through the ice, you really have 10-15 minutes before your capacities are greatly diminished,” said Caughlan. “Your body starts going numb, you start going into hypothermia. There’s a lot of things going against you.

“So, time is critical to respond to someone falling through the ice.”

Because the men who died during the Keyhole Reservoir rescue were in the cab of a utility task vehicle, they were unable to escape before that time slipped away, he said.

Two others who fell through the ice made it out with the help of trained professionals.

“One of our rangers, Brad Purcell, he and a Game and Fish officer found the original guy who fell through the ice crawling (out of the water), and they helped drag him back to shore,” said Caughlan.

Right Place, Right Time

Caughlan pointed out that because Wyoming is very rural and resources are generally far away, having trained park rangers nearby is someone’s best bet in the event of a fall through the ice.

“We are the closest resources when this happens,” said Caughlan. “If we wait for search and rescue teams or the sheriff’s department to show up, they may be 45 minutes to an hour away.

“But if we’re at least there on the park, we have the rescue suits and we have the ropes, we have the capabilities of doing it.”