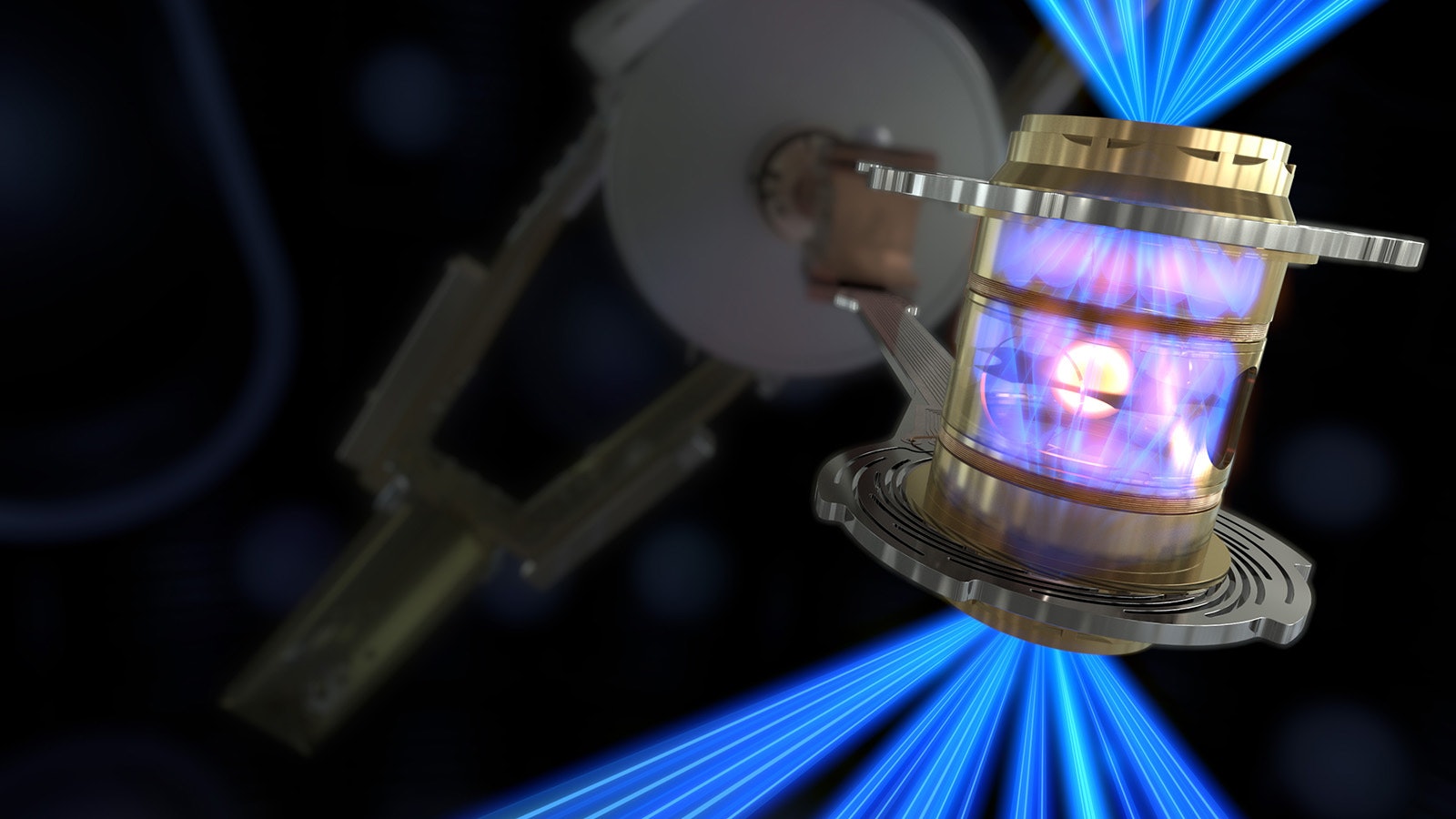

Researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, conducted a controlled fusion reaction that produced more energy than it took to start the reaction.

But that doesn’t mean they produced a net amount of power from the experiment.

The experiment was the first in history to reach this milestone, which is known as a scientific energy breakeven, meaning it produced more energy from fusion than the laser energy used to start the reaction, according to a statement from the Department of Energy.

Nuclear fusion, unlike nuclear fission, is a process in which two light atomic nuclei are combined to form a single heavier nucleus. Put simply, two atoms are smashed together with lasers, producing lots of energy without any carbon dioxide emissions.

It’s different from nuclear fission, where heavier atoms are broken apart to produce energy. The advanced nuclear reactor planned for Kemmerer uses fission reactions.

Unlike with fission reactions, fusion reactions don’t produce long-lived radioactive nuclear waste.

When two hydrogen atoms are smashed together, helium is the main byproduct. Fusion also doesn’t rely on a chain reaction, making it safer — at least in theory.

20 Years Away

Does this mean we can shut down coal plants and take down wind turbines? Not quite.

“The old joke with fusion is that it’s always 20 years away, and it’s been like that since the mid-20th century when people started studying it,” said Dr. Caleb Hill.

Hill is an associate professor of chemistry at the University of Wyoming and co-director of the Nuclear Energy Research Center, which is a new research center in the UW School of Energy Resources. The center is focused on nuclear energy and related applications.

Major Breakthrough

Hill is a chemist by training and not a fusion expert, but he knows some things about the fusion process.

Hill said the milestone at the Lawrence lab is a major scientific breakthrough, but having fusion reactors online and producing energy is still decades away.

The Lawrence lab uses about 200 lasers to create intense heat — more than 180 million degrees Fahrenheit — and compress hydrogen atoms with pressures 100 billion times the Earth’s atmosphere, according to the Wall Street Journal.

This is essentially the same conditions that exist inside stars, which derive their energy from fusion processes.

Ideal Source

Hill said a fusion reaction kicks out a lot of neutrons.

“It’s going to end up making things pretty damn radioactive through the process, so it’s not a perfectly clean process yet,” Hill said.

If they can get it to the point it operates safely and practically long-term, Hill said, it would be one of the most ideal energy sources available, rivaling any other in use today.

The problem confronting fusion researchers is they have to use a lot of power to get the reaction started. The amount of energy that came out of the lasers was less than the energy the reaction produced, but the energy to drive the laser emitters nullified those gains, Hill said.

“We’re still a long way off from achieving a true breakeven in terms of the efficiency of the overall system,” Hill said.

Scientifically Important

There’s another step as well to take the energy produced from the reaction and harness it in a functioning power plant.

For example, the Natrium reactors in the proposed advanced nuclear reactors in Kemmerer will use molten salt as a heat exchange fluid that will drive a generator.

Because of all these hurdles, Hill said he’s not getting too excited about this latest development in the world of fusion, but he doesn’t dismiss its value to science.

“I’m a little cynical when it comes to announcements regarding fusion. But scientifically, it’s a very important step,” Hill said.