Wyoming lawmakers haven’t drafted a law allowing the Northern Arapaho Tribe to build new casinos on state lands to help fund the state’s public schools, but they could by January.

The Northern Arapaho tribal government in September proposed a business deal: Wyoming would let the tribe build at least one casino on state-owned trust lands, and in turn the state would receive a cut of gambling profits to fund its public schools.

The tribe originally offered that 75% of proceeds would go to “individuals and entities located within the state of Wyoming.”

The tribe revived its pitch Monday during the Legislature’s Joint Revenue Committee meeting in Cheyenne.

Travis McNiven, lobbyist for the tribe’s government, described the venture as a homegrown effort designed to keep money in Wyoming, since the tribe is based in Wyoming. He also indicated the casino would be best placed near a state border or on an interstate highway.

“Certainly, I think, out-of-state populations and people going through the state are certainly key, from what we’ve learned,” said McNiven.

Goodbye, Dry Country

The Northern Arapaho Tribe has two casinos on the Wind River Indian Reservation, which operate under a federal license and in federal jurisdiction.

If the state allowed the tribe to open a casino on state lands, the gaming licensure would go through the Wyoming Gaming Commission rather than the federal government, giving the state more oversight, McNiven said.

Having a casino on state rather than reservation land would allow the tribe to seek a liquor license for the new establishment, which is something the tribe lacks in its current casinos.

The reservation is dry, meaning it’s not legal to sell liquor there.

Millions And Millions

Wyoming and its local entities put about $1.5 billion into the state K-12 public school operations every year. Some of the money historically has come from the energy sector, including coal, which has an uncertain future as renewable energy sources gain traction.

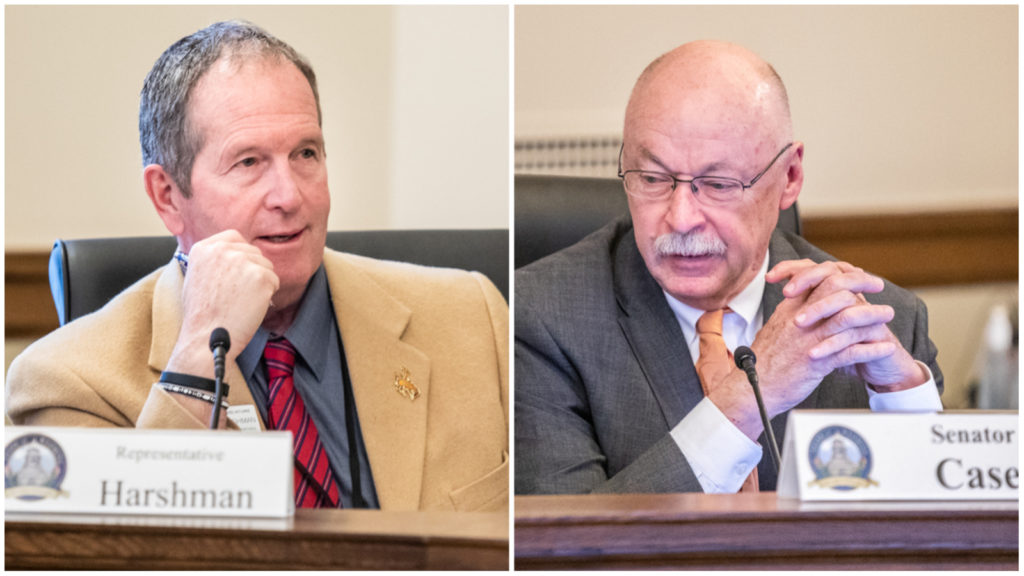

Committee Co-chair Rep. Steve Harshman, R-Casper, said the committee is looking for a new funding source capable of generating $50 million, presumably for each two-year budget cycle.

“You’re still good with that (amount)? You’re still there?” Harshman asked McNiven.

“The short answer is yes,” said McNiven, adding that preliminary studies of the project indicate that “these facilities … limited in scope, one or two locations, would certainly meet the committee’s desired goal.”

Sovereign Immunity

Generally, American Indian tribes cannot be sued. They operate as lesser sovereigns and have sovereign immunity from lawsuits. Tribes such as the Northern Arapaho can waive their sovereign immunity when entering into contracts with other entities, such as the state of Wyoming.

If the Northern Arapaho tribe is willing to waive its sovereign immunity, it could then be sued should the deal go south.

Rep. Mark Baker, R-Green River, asked the tribe’s in-house legal counsel Claire Johnson how the parties would work through a dispute.

“What if one entity were to become in violation of the act or the Wyoming Gaming Commission, how would that impact the other entity?” asked Baker.

After some clarification, Baker seemed to be asking whether a violation of the tribe’s federal gaming license would impact its state gambling enterprise.

Johnson said the federal license status would have no bearing on the state license since those are different jurisdictions.

Neither party addressed the sovereign immunity question in the instance of state contract breach, however.

First In The Business

The Northern Arapaho Tribe pioneered gambling in Wyoming by establishing a Class III gaming license from the federal government in about 2006. The license was unique in that the tribe was allowed to cut the state out of profits.

Wyoming lost its opportunity in 2002 to hold a gaming compact with the Northern Arapaho Tribe, because a federal judge ruled that the state failed to cooperate “in good faith” with the tribe. Wyoming had refused to accept the tribe’s gaming terms within the contract deadline.

Since then, skill-based gaming has been introduced in Wyoming. Skill-based machines are not considered chance gambling because a player can learn from game patterns and has the opportunity to win every time.

Except for historic horse racing, games with no skill element could not legally operate under the Wyoming Gaming Commission, so the tribe may have to invest in skill-based games, historic horse racing, sports betting, or a combination – or seek a change or exception in the law to operate games of chance at the new facility.

With skill-based games alone, a facility can contain no more than four games under state law.

Equal Protection

Revenue Committee Co-chair Sen. Cale Case, R-Lander, said he feared that working out an exclusive deal with the tribe on state-controlled lands could violate the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution and make the state vulnerable to lawsuits.

Jason Crowder, deputy director of State Lands and Investments, said the law doesn’t require competitive opportunities for commercial leasing like the tribe is proposing, though the law requires open auctions for land sales.

Case spoke in favor of the tribe’s proposition, saying it’s a “good faith” offer.

State Trust Lands

Legislators quarreled about balancing their directive to use state-owned land to fund public education versus their duty to protect individual residents.

Sen. Tom James, R-Green River, disputed the notion of setting up casinos on land leased for grazing by generations of ranchers.

“I’d be really concerned about that, because for families that depend on those grazing leases for their existence of their farms … they should take priority,” said James.

Sen. Stephan Pappas, R-Cheyenne, countered, saying the duty toward the lands is to get the most efficient revenue streams to support education.

“I don’t think the type of lease is the priority – I think it’s the return on the lease,” said Pappas.

James volleyed, “We as elected officials are in charge of looking after the people of Wyoming, not money. We should be looking after the interests of these people, and that should be protecting those grazing leases.”

Case indicated that grazing leases would pale in profitability compared with gambling revenues.

Crowder said that 98% of state lands have grazing leases on them now. He also said that the casino or “any real commercial opportunity that comes to us” doesn’t need to take up a whole parcel, and there still may be grazing opportunities.

When the state eliminates someone’s grazing opportunities, said Crowder, it pays an impact fee to that person.