By Renée Jean, Business and Tourism Reporter

renee@cowboystatedaily.com

Fog shrouded the view as Mark Pedri stood on the banks of the Moselle River, the city of Metz, France, beckoning from far, far away.

Pedri had come to the banks of this river so near the German border in pursuit of secrets and unspoken words, to stand in all the places his grandfather Sgt. Silvio J. Pedri had been during World War II.

Silvio had crossed this river with a small, diversionary force. Outmanned and outgunned, they’d never stood a chance.

“The river flooded behind them,” Pedri told Cowboy State Daily. “And then they weren’t able to get any of the reinforcements that were promised to them.”

Still, Silvio and the other soldiers managed to hold out for days under heavy gunfire.

Crossroads

They were captured just one day before their promised reinforcements finally arrived. From there, Silvio was sucked into a series of prisoner of war camps, deeper and deeper into Nazi Germany.

History, meanwhile, tells that the diversion Silvio had been part of succeeded.

Metz, the historic crossroads, fortified through the centuries to withstand war upon war, finally fell by force, something that had never happened in recorded history.

“Metz was one of the last strongholds that Nazi occupied in France,” Mark Pedri said. “It was a very fortified city, and we had been trying to take the city, but with no luck and pretty high casualties.”

Stunning Revelation

It was not the stories that grandfather Silvio had told Mark Petri from his home in Rock Springs that brought the young Wyoming filmmaker to the banks of the Moselle, working on a documentary titled “Dear Sirs.”

Growing up, Mark had always felt close to his grandfather, but the Moselle River was part of a secret world that his grandfather had never even mentioned.

To learn that Silvio had been one of the iconic Iron Men of Metz was for Pedri a stunning revelation. But it was only the latest in what had been a long string of them, leading him to this moment and this place in time.

Something He Didn’t Know

The first revelation had been not long after his grandfather’s death, when Pedri found a kitchen knife wedged beneath his grandfather’s mattress and box springs.

He held the knife, thinking of his grandfather and all the times Silvio had grown emotional or brushed off questions about the war.

Pedri had thought he’d known his grandfather, but here was something he had not known about at all.

“It just didn’t fit the version of him that I knew,” Pedri said.

In his grandfather’s office, Pedri opened desk drawers. He found two types of documents. There were papers related to Silvio’s mobile home park. No surprises there.

And then there were the papers that dealt with his time as a soldier in World War II.

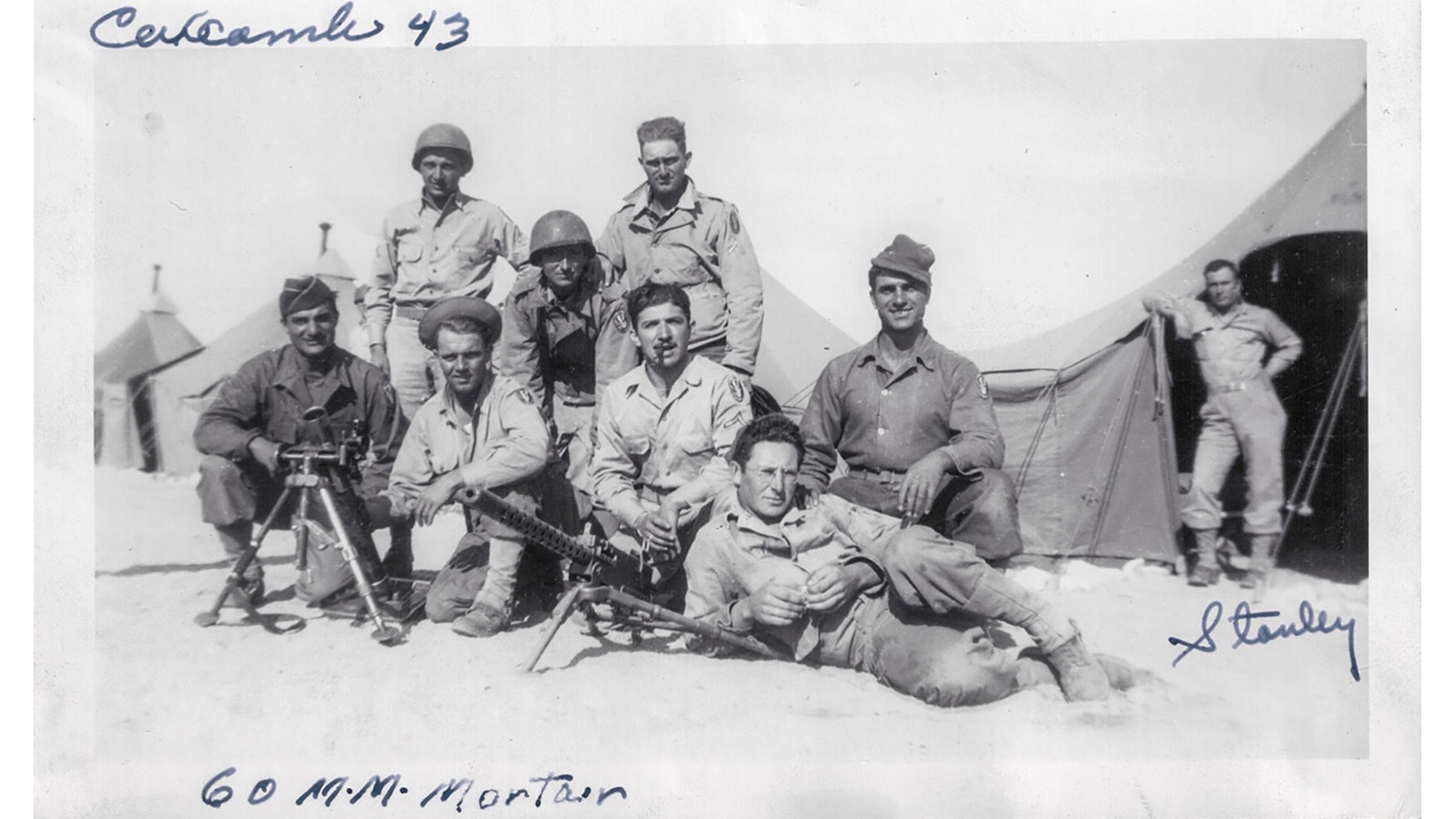

Pedri looked through everything – every photograph, every document. He could not sleep until he had seen it all.

Among these papers he found 10 index cards with short sentences.

These were sentences Pedri could hardly believe. They described in sparse words the conditions at Stalag 10B. A Soviet prisoner of war camp that was ultimately merged with 10,000 Jews from a concentration camp in the waning days of World War II.

Elusive Story

Pedri had only intended to stay one night at his grandfather’s place. But he had found too much to see, too much to understand.

He could not leave.

Instead, Pedri moved in, deciding that his grandfather’s life should be his next film project.

He wanted to connect, to understand all of the man he had thought he’d known.

But the more he pulled at the loose threads from his grandfather’s life, the more he found what had previously been unknown.

“It revealed a version of this person who didn’t live in the house,” Pedri said. “That person lived in Germany, in a prison camp. So that’s when I decided that just having this information on paper was not going to be enough.”

On Location

Pedri decided to go to Germany.

He would see everything he could see with his own eyes, hear everything that he could with his own ears, and be in the same space his grandfather had been when he was a soldier in World War II.

He worried, though, that even that would not be enough.

His grandfather’s story might well forever elude him.

Echoes Through Time

In Germany, Pedri discovered more than he could have imagined.

“I think that’s what the film is about,” he said. “It’s really taking people on that journey and seeing how much a place can still hold that part of who someone is even after they’re gone. You can go to that place, connect with them, and learn about them.”

Everything from the weather, how cold it must have been — and even the fact that it was colder then than now.

“One of the camps he had to work in was a scrap yard, a metal scrap yard, which still exists today,” Pedri said. “To go and see that this place is still a scrap yard, that was pretty surprising.”

At a barn where his grandfather would have taken cover, bullet holes still remain, traces of the history and the man Pedri is trying to understand.

“The farmers, you know, still pull up shells from their fields and to them, you know, it’s their history,” Pedri said. “So when we were there, they were very passionate about making sure that we went everywhere and that we were taken care of, and that we had as much information as possible.”

Americans were their liberators, Pedri said, and he felt himself receiving the same treatment.

“You know, because my grandpa was there, they saw me as someone that they wanted to take care of and to show hospitality toward,” he said.

Stalag 10B

Pedri’s grandfather had been captured toward the end of the war at a time when Germany was rapidly moving prisoner of war camps, trying to keep soldiers from being liberated by the Allies.

“As the Allies got closer, he would get loaded onto a train or marched to a different camp further inside Germany,” Pedri said.

Among the last of these was Stalag 10B, a Soviet prisoner of war camp.

“There were very few Americans there, and those prisoners were treated very differently based on their nationality and ethnicity,” Pedri said.

In the last month, right before the camp was liberated, 10,000 Jews from a concentration camp called Neueganne were marched into Stalag 10B.

This was what the notecards Pedri had found in his grandfather’s office were about.

Hard To Believe

In the United States, many people told him that just couldn’t be, that his grandfather had to be mixing up his memories.

But in Germany, Pedri found a tremendous number of video testimonies from survivors backing up all of the experiences Silvio had written about in such sparse words on the notecards in his office.

“It was like he wanted to write down what happened, but he would only get maybe two or three sentences out at the time before he would stop,” Pedri said.

‘One-Third Of The Transferred Prisoners Died’

Many, many people died in Stalag 10B – not because it was an extermination camp, but the Nazis didn’t want to be caught with the concentration camp Jews, so they moved them, quickly, and without provisions.

“Out of those 10,000 people, one-third of the transferred prisoners died,” Pedri said. “At that time, it was late spring, but I mean, they had no provisions whatsoever.”

In fact, anyone who tried to help the starving people in the camp were quickly shown the futility of their efforts.

“If someone threw a piece of bread over the fence, the guards would shoot whoever tried to retrieve the bread, just, you know, to show how little power any of the prisoners had,” Pedri said. “That was definitely the darkest moment of learning about my grandpa’s journey and what we know of what he went through, what he may have witnessed on a large-scale.”

Joy In Simple Things

One of Silvio’s favorite things to do once he came back to Wyoming was to sit on the porch and listen to trains in the distance and just spend time with family.

“I think definitely, you know, the simplest things in life were what brought him the most happiness,” Pedri said. “Coming back to Wyoming and having a family was from my experience. He dedicated his whole life to that.”

Pedri has had time to reflect on his grandfather’s story and the documentary “Dear Sirs” that he has made about his pursuit of a complete picture of his grandfather, Silvio Pedri.

“I took away a connection to my grandpa that I don’t know that I would have ever been able to have while he was alive,” Pedri said. “So in some ways, him not telling me the story allowed me to learn it in a way that wouldn’t have been possible.”

The documentary “Dear Sirs” will be screened at 6 p.m. Friday at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. There also will be a free virtual screening through the weekend.

Importance Of Passing On Stories

But the larger takeaway that he hopes the world’s remaining veterans will consider is the importance of their story to their family members and how those stories are being lost as veterans go to their graves, their stories untold.

“If they’re not ready to share that, you know that’s OK, because that’s part of their journey, but it shouldn’t be them feeling like they need to protect their family from something,” Pedri said. “Keeping it in has been very destructive. Having an outlet, and a community, and being able to open up and share a part of your story is very healing.”

The other thing he hopes viewers will take away from the documentary is not just thanking veterans on Veterans Day, but asking if there’s anything about their service they’d like to share.

Saying, “I’m here to listen,” could make all the difference.