From the pull of the trigger, roughly 24 seconds elapsed before forward spotters heard the telltale plunk of a 422-grain copper bullet piercing the thin metal target.

The shooter was 4.4 miles away, a distance so great, the Earth’s rotation came into play.

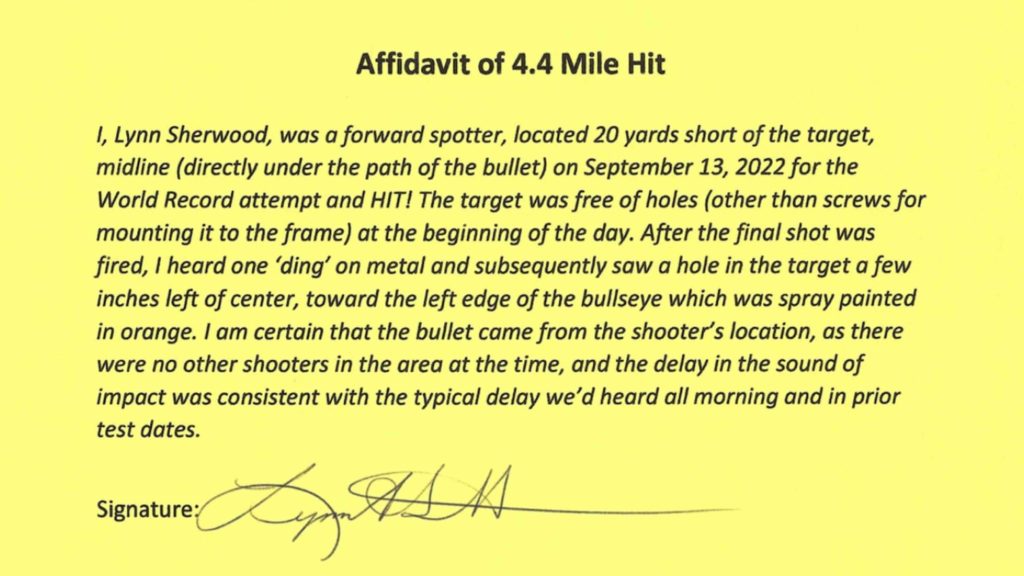

It was a new world record for a rifle shot, set by the Jackson-based Nomad Rifleman team led by Schott Austin and Shepard Humphries. The shot was made with a custom-built rifle chambered for the .416 Barrett cartridge.

During a Zoom interview Tuesday with Cowboy State Daily, Humphries declined to identify the team member who made the shot.

It beat the team’s previous Wyoming state record of 3.06 miles. It also broke the previous world record shot of 4 miles set in 2020 by Paul Phillips of Texas.

The Wyoming team “had easier conditions” than Phillips because of the thin air at about 7,000 feet in elevation near Pinedale, where the shot was made Sept.13, Humphries said.

Still, even with the Wyoming air working in their favor, it was nothing short of miraculous for the shot, the 69th attempt that morning, to land inside an 8-inch orange bullseye. The bullseye had been painted in the center of a white, rectangular target measuring 120 inches wide and 92 inches tall.

Two Years In The Making

The team had been working to break the Texan’s 4-mile record since it was set. However, supply chain issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic slowed the process of getting components to build the custom rifle, Humphries said.

Parts came from all over the world.

“The muzzle brake came from New Zealand,” he said. “The barrel came from South Dakota and then went to Arkansas for structuring.”

Other components came from Canada and elsewhere, and the rifle was assembled by S&S Sporting goods in Driggs, Idaho.

The rifle’s scope zooms from 6 power all they way up to 35 power magnification.

“I’m not sure where it was set during the shot,” Humphries said. “When we’re shooting extreme distances, we don’t zoom all the way up to full power, because that can make things get fuzzy. We back off just a bit.”

Science Of The Shot

Landing a bullet on target at 4.4 miles was “simply phenomenal,” said long-distance shooting enthusiast David Asmuth of Laramie. He’s the president of the Laramie Rifle Range board of directors.

“It’s a one-in-a-million shot. They said it’s not statistically repeatable,” he said. “The amount of precision and time that went into that shot was simply amazing.

“When a bullet is in flight for that long, you have to take into account the rotational speed of the earth. What you’re shooting at isn’t going to be in the same place it was 24 second ago when you pulled the trigger.”

Ashmuth said the longest shots he’s ever made were 2,220 yards with a bullet flight time of about 4-5 seconds.

A massive flight arc had to be calculated to make the 4.4 mile shot work, Humphries said.

The angle of the rifle’s barrel, coupled with shooting from a ridge above the target, accounted for the arc in the bullet’s trajectory, he said.

“That made it more like artillery, where you’re lobbing it in,” Humphries said.

The .416 Barrett cartridge is made by “necking down” a .50 Browning Machine Gun (BMG) round to accommodate the roughly .40-caliber bullet. It’s a relatively short, stout bullet that proved ideal for its purpose, Humphries said.

“Traditionally in extreme long-range shooting, we wanted long, skinny bullets,” he said. “However, we discovered that as a bullet crosses over into subsonic velocity, it flies better if it’s shorter and fatter.”

The .416 Barret bullets were leaving the rifle’s muzzle at a velocity of roughly 3,300 feet per second, Humphries said. They dropped into subsonic velocity at about 1,100 feet per second and were traveling at a downward angle and about 600 feet per second as they reached the target zone.

Regarding it taking 69 shots to hit the mark, with all the variables that had to be taken into account, “we were thrilled it was so few,” Humphries said.

Thanks to the rifle barrel’s structuring, which involved specialized dimples and venting holes, overheating wasn’t a problem.

“The barrel never got any hotter than about 80 degrees,” he said. “That allowed us to take a shot every minute or two or three.”

Sound, Not Sight

Forward spotters were in five bullet-proof bunkers near the target, Humphries said. They had to rely on their ears rather than their eyes to guide the shooter’s adjustments.

“When we were making 2-mile shots previously, we could rely on dust from the bullet impacts to help us walk the shots in to the target,” he said. “With these shots, we discovered we couldn’t see most of the bullet impacts.

“The bullet is coming down so slowly, and at about a 48-degree angle, it was just penetrating into the ground without kicking up dust.”

Instead, spotters had to listen for the bullets thudding into the ground and radio back to the shooter to adjust accordingly, he said.

What’s Next

Records are made to be broken, but Humphries said he isn’t certain whether his team will set the next one.

“You know, we haven’t decided yet,” he said about attempting to go farther than 4.4 miles. “This project was much harder than we anticipated.”

While extreme distance shooting teams keep “some secrets,” he said they also don’t mind sharing much of what they’ve learned, giving others a chance to keep stretching the distances.

“Now, the next people who beat us – whether that’s in a few days or a year or 10 years from now – they have some knowledge from our shot that they can use,” he said.