People who are drawn to an event created to showcase the skills of our canine companions come from all walks of life, providing a rare opportunity for those with differing political ideologies to learn about and engage with one another – because dogs are apolitical.

An annual gathering to celebrate man’s best friend has resulted in fascinating conversations about controversies involving their wild cousins.

Every September the week following Labor Day, a grassy meadow at the edge of the town of Meeker, Colorado, springs to life as it hosts a herding dog championship.

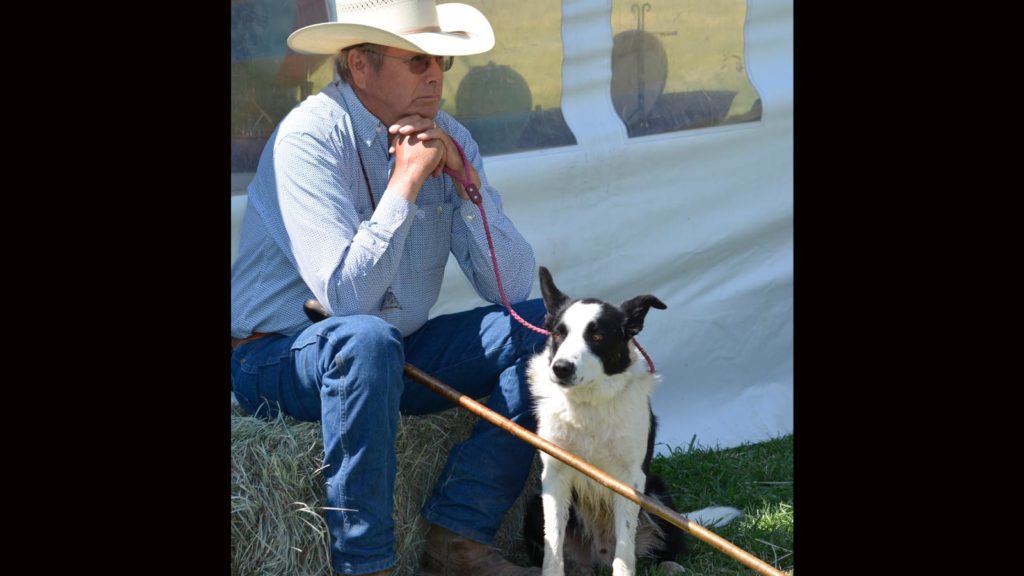

The Meeker Classic Sheepdog Championship Trials routinely draws top sheepdogs and their handlers from throughout the United States and Canada, and visitors from throughout the world.

Colorado sheepwoman Julie Hansmire brings a flock of 700 fine-wooled yearling ewes off the mountain for the 5-day trials, and herding dogs compete for high scores in increasingly precise and difficult movements and patterns as the clock ticks.

Of the 135 dogs in this year’s competition, Wyoming was well represented by 10 dogs with six Wyoming handlers.

Multiple dogs from Kaycee, Sundance, and Clearmont competed, plus a dog from Sheridan. One of Kaycee sheepman and dog handler David Soppe’s dogs made it into the semi-finals for the top 30 dogs, but none of the Wyoming dogs made it into the finals competition reserved for the top 12 dogs.

In the end, the champion title was earned by South African champion dog trainer Faansie Basson, now of Texas. Second place was won by a Virginia dog and handler, and another of Basson’s dogs took third place.

I’ve had the pleasure of making repeated returns to the Meeker Classic, not as a dog handler, but as a guest of the Meeker Classic and sponsored by the Colorado Sheep & Wool Authority.

I was stationed in a tent sponsored by Purina to engage people in conversations about wolves from my perspective and experience as a domestic sheep producer. It’s a controversial subject, but one that kept my tent busy with people from across the country.

I also had the pleasure of visits from other Wyomingites, including those from Cheyenne, Lusk, Newcastle, Cody, Lander, Dubois, and a former Sublette County resident.

I had brought along two spiked collars that we use to protect our livestock guardian dogs from wolf attacks. People walking by would stop and inquire as to their purpose and were stunned to learn of their use. Most had never realized that the guardian dogs, there to protect the livestock, may themselves need protection.

Most of the cattle ranchers stopping by wanted to talk the details of their situations, describing resource characteristics and constraints that may vary by season, from recreational pressure to nearby subdivisions and prey populations, and how those factors weigh into their decisions on the predator deterrence measures they may deploy to keep their livestock safe from wolves.

I visited with so many people who reside in Front Range communities with an honest interest in understanding the complexities and impacts of the Colorado wolf reintroduction program, which was passed when wolves were a state-protected species, but a later court decision declared all wolves in Colorado as fully endangered under federal law.

When ranchers approached to talk about their scenarios, there were numerous times that urbanites stood alongside, listening, asking questions, and learning. Again and again, people pointed out the complexities involved in deterring predators away from livestock and how the wolf population may be managed in the future.

My longest conversations were with ranchers, talking about how to deter predators in their specific scenarios. My stacks of free publications detailing non-lethal methods to deter predators were gone by lunchtime of my second day in Meeker.

I openly talked about my view of the need for lethal control of predators that repeatedly kill livestock, and how giving ranchers the authority to kill a wolf caught in the act of killing stock isn’t enough because the reality is that these attacks are rarely witnessed, let alone having a person in position with the equipment to make the successful shot.

I talked about how federal and state wildlife officials should be given both the authority and responsibility to help solve conflicts, including lethal control. All these conversations involved discussions about the need for local collaboration and solutions rather than blanket mandates from above.

Wolf advocates expressed concern about how lethal control of even one wolf could disrupt a pack’s social structure or behavior, and they seemed surprised when I replied that was the specific outcome sought with lethal control. If the lethal control of one wolf can disrupt the repeated livestock depredation by the pack, that’s a success. But often it’s not enough when it comes to a problematic pack.

Several ranchers and wolf activists suggested that “If you have a good pack, leave it alone.” That is a wise adage, but I advised to remember that a wolf pack is not a static being. It changes over time, as animals are born, mature and die, and animals enter and exit the pack – all of which may result in changes to the behavior of the pack.

Our discussions often concluded with a discussion of how people are drawn to the wild, working landscapes of the West, and our common desire to keep these landscapes shared. A fitting conclusion to the Meeker Classic, with man’s best friend serving as unifier.

Cat Urbigkit is an author and rancher who lives on the range in Sublette County, Wyoming. Her column, Range Writing, appears weekly in Cowboy State Daily.