By Aaron Turpen, Cowboy State Daily columnnist

The advertised fuel economy for your vehicle is probably not the MPG returns you’re going to get while driving around Wyoming. There are several reasons for that. Some of which you may not know.

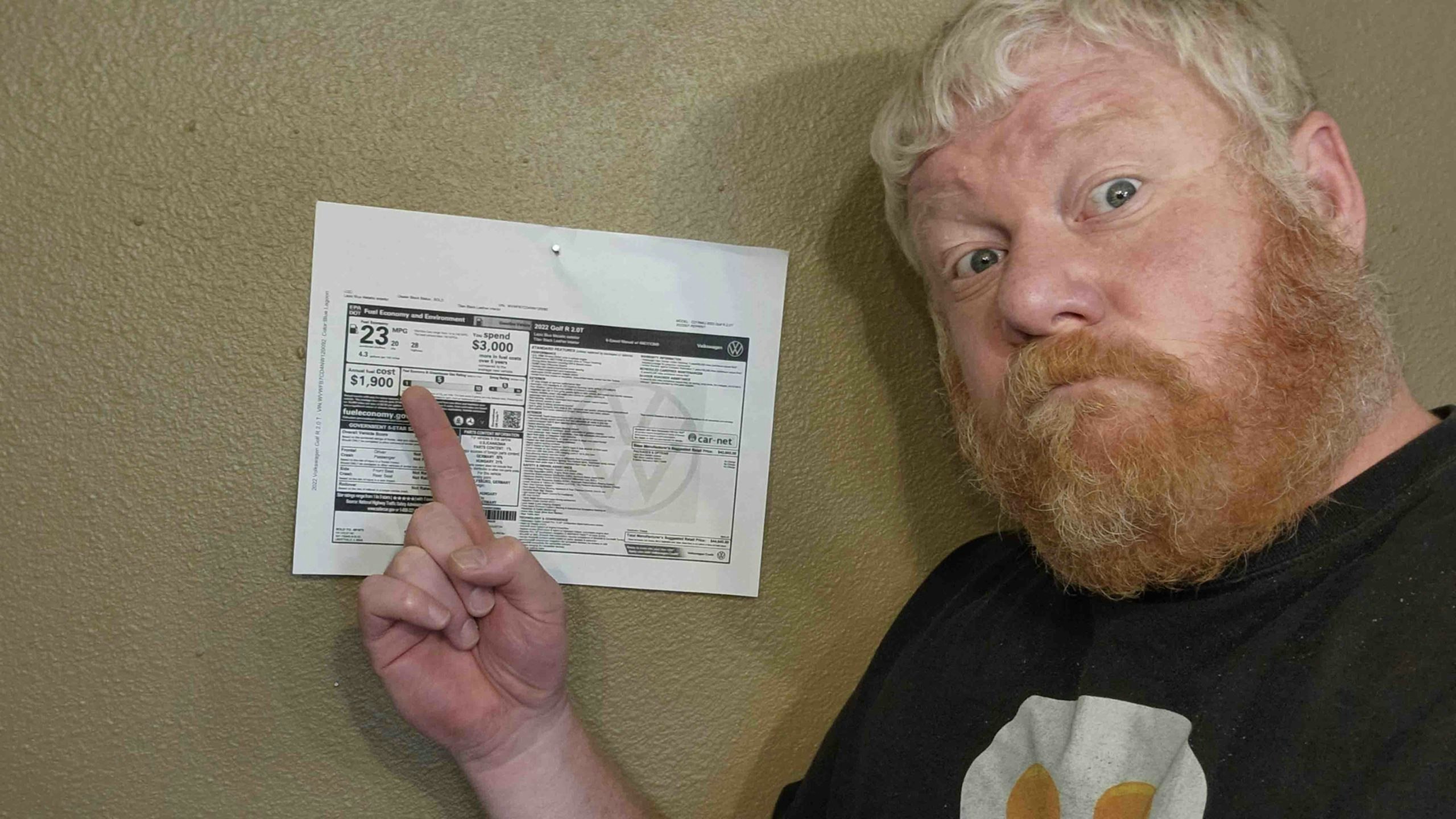

Federal law requires that every new passenger vehicle sold have a standard window sticker (called a “Monroney” in the business) that displays specific information about the vehicle. The information includes fuel economy estimates from the Environmental Protection Agency. Those EPA fuel economy estimates are sometimes correct, but are usually wrong.

As a part of what I do for a living, I drive a lot of cars. Big ones, little ones, pickups, hybrids, you name it. Most of the time, the EPA estimates for MPG returns are wrong — especially in Wyoming. It’s a well-known automotive industry expectation that those numbers on the sticker won’t happen for most people who buy that car.

As part of the process of testing a vehicle, I do a highway loop that runs from North College in Cheyenne, across Interstate 80 to the TA truck stop and back. That loop is about 42 miles, with varied elevation, starting from and ending at the gas station on 12th. I top off the vehicle before going out and then do it again when I return and use the numbers from the pump to calculate fuel economy. For most vehicles, it’s 1-3 mpg lower than what the sticker said it should be for highway MPG.

The short version of this is that being where we are, we are at high altitude. Our altitude at 6,400 feet in the air means we have less oxygen in our atmosphere than does, say, San Diego, California with an average altitude of about 60 feet.

Less air means the engine doesn’t get as much O2 mixed with the fuel for burning, which means lower fuel economy. Crosswinds are another hazard we deal with regularly here. We also drive at higher speeds than does much of the country, with posted speed limits of 70 to 80 miles per hour being a norm on our highways. One of the benefits of all this wide open space is we don’t have to putter through it most of the time.

The EPA, however, doesn’t test vehicles at 6,400 feet. Most vehicles are tested within a couple of hundred feet of sea level. Those MPG tests posted at fueleconomy.gov are actually done by manufacturers, who test early production prototypes or models and submit the results to the EPA.

The EPA then spot checks (retests) about 15-20 percent of those submissions to make sure automakers are on the up and up. But because altitude isn’t specified in the EPA’s requirements, manufacturers game it by doing the test at low altitude.

The tests also aren’t conducted in the real world. They are done in a laboratory: an enclosed space where the car or truck sits on a dynamo (essentially giant rollers) and drives at given speeds for a given amount of time. The vehicle is controlled by remote (using a computer) without a human on board. Then fuel usage is measured and an MPG number results. Pressure from the dynamo’s rollers simulates light crosswinds and elevation changes, in a pre-determined and required setup. Speeds for the highway (about 55-60 mph) and for around town (about 25 mph) are tested. A combined fuel economy number is calculated using 45 percent of the highway result and 55 percent of the city result for an “average.”

If that sounds a little contrived, well, most in the industry agree that it is. But for lack of a better, more controlled option simulating the real world, that’s what we’ve got.

But there are ways that we can improve our fuel efficiency while on the road. Eliminating short trips and combining them into one bigger trip is one. On short trips, a vehicle won’t reach optimum operating temperature and thus uses more fuel. A longer trip–even one with several short stops inside of it–will reduce this and improve MPG. Same with cold weather travel, where idling for long periods to warm up the car (not recommended) and driving short distances before stopping is terrible for fuel economy.

Driving like everything is a race is another way to tank your MPG returns. Aggressive acceleration, hard braking, and tailgating are all habits that are best left to the big city rat race folk. This kind of driving is the biggest contributor to low fuel economy returns. Leave the aggressive driving and cutoff bird flipping to Coloradans. We’re better than that.

The last issue is maintenance. A well-maintained vehicle is more efficient in every way. Keeping your car clean inside and out might seem inconsequential, but less clutter and junk means less weight and that means better mileage. Good maintenance with tire rotations, lubrication, and having all bodywork actually attached makes a difference in how well your vehicle operates. There’s a reason we equate badly maintained vehicles with manure storage.

To summarize, while your vehicle’s MPG may not be equal to that on its window sticker, it can be close if you want it to be.

Aaron Turpen is an automotive journalist living in Cheyenne, Wyoming. His background includes commercial transportation, computer science, and a lot of adventures that begin with the phrase “the law is a pretty good suggestion, I guess.” His automotive focus is on consumer interest and both electronic and engineering technology. Turpen is a longtime writer for Car Talk and New Atlas.