After a grieving mother on Tuesday told lawmakers of her son’s tragic death after a crosswalk collision in Cheyenne, a legislative committee started drafting a new vehicular homicide law.

The Legislature’s Joint Judiciary Committee agreed Tuesday to direct the Legislative Service Office to draft an enhanced version of the state’s law against vehicular homicide.

Current law designates the crime as a misdemeanor punishable by up to a year in jail and a $1,000 fine. The bill being drafted by LSO would add a possible felony-level penalty for drivers who kill pedestrians within crosswalks or school zones.

Higher penalties for drivers who cause pedestrian fatalities are possible under the law currently. However, more intense penalties depend on the defendant’s state of mind – such as the disregard for life required for aggravated assault charges or the premeditation and malice required for first-degree murder.

‘If Only I Had Known’

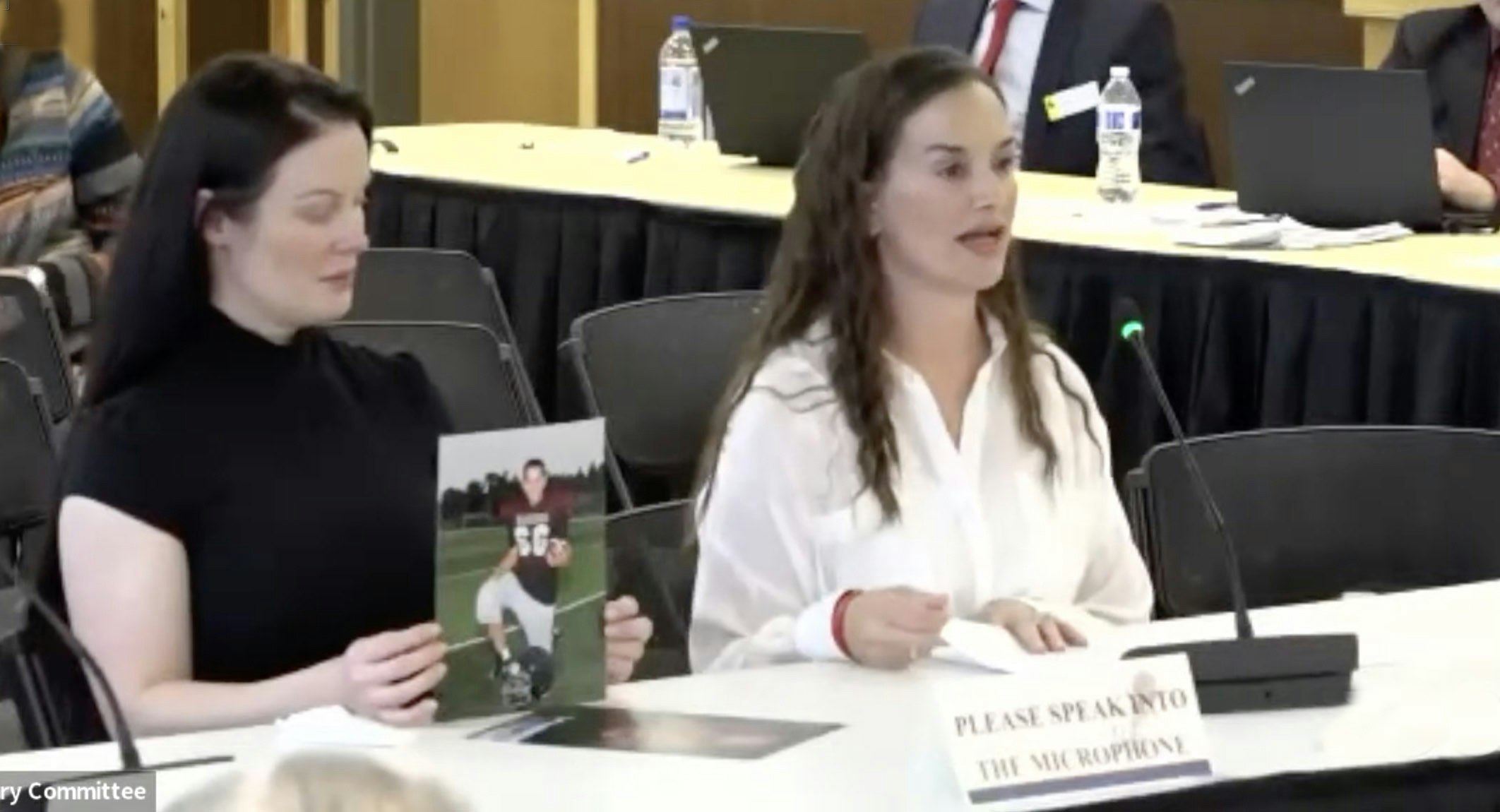

Janelle Jones became emotional as she told the committee of her son, Makaili, or “Mak,” and how he died Nov. 5 following a crosswalk collision with a distracted driver.

Nothing about that day seemed different when it started, Jones said.

“I made him breakfast,” she said. “I set out his allergy medicine. I woke him up to get ready for school. We chatted casually over breakfast about the upcoming day’s events, and he was going to meet a friend after school and go to a movie.”

When the boy stood to leave, said Jones, he beamed while uttering a bit of teenage slang.

“Mak turned to me and flashed me the biggest smile, and enthusiastically said ‘Mom, doesn’t my outfit look fresh?’” She recalled with a tearful laugh.

“I said ‘Yes, you do look cool,’” she said, adding “If only I had known it would be the last time I would see my son smile.”

Seven minutes later the assistant principal at McCormick Junior High School called Jones, telling her to get to the school.

Sirens wailed.

Jones found her son “lying in the road,” surrounded by first responders performing CPR.

“I sat on the curb and watched in horror,” she said. “My hands wouldn’t work to dial my husband’s number on the phone. I forgot how it worked.”

Paramedics continued their CPR efforts the entire way to the hospital in an ambulance ride Jones did not get to share.

Jones was escorted by law enforcement to the hospital, where she was overcome by furious denial.

“No,” she remembered thinking when she saw two chaplains appear. “They cannot tell me this.”

An emergency room doctor and neurologist met with Jones. The neurologist warned her that if Mak survived, he’d be paralyzed from the neck down and have little to no brain function.

X-rays and CT scans were taken while ventilator tubes and other emergency procedures were followed, to no avail. Jones was allowed to join her son in his room.

“My son died in my arms at 10:06 that morning,” said Jones. “I had to leave the hospital without my baby.”

Not Looking At The Road

Citing “dash cam” footage in the case, which is still ongoing, Jones said that her son waited at the crosswalk facing the school. Three vehicles in a line stopped for him, in the westbound lane.

But Mak hadn’t seen a vehicle in the eastbound lane which collided with him after the woman driving had been watching her daughter.

“She only turned to look at the road when her daughter shouted ‘MOM!’” said Jones.

“While there was no intent,” she continued, “this was not an accident… this was 100% preventable.”

Missing Piece

Jones told lawmakers that she has started a nonprofit organization called “For Mak” and has raised $110,000 for safer crosswalk systems.

But she said she believes there’s still a missing piece of the puzzle – criminal deterrence.

Other states such as Colorado and Utah, Jones noted, have felony punishments for vehicular homicide.

She hopes Wyoming would follow suit, adding that she believes harsher penalties may compel drivers to pay more attention and possibly prevent collisions.

In the committee discussion, Rep. Art Washut, R-Casper, told his fellow committee members he doubted simply enhancing the penalty for vehicular homicide would deter distracted driving because most people don’t pay attention to criminal penalties.

However, he added that as a punishment, “it’s not inappropriate to consider a felony level crime for the taking of a life.”

Rep. Ember Oakley, R-Riverton, said while the topic is highly emotional, lawmakers should use caution when assigning felony punishments for accidental crimes.

“I think the argument for (punitive) deterrence when you’re discussing accidents is low by definition,” said Oakley, adding that most significant-level crimes are punished harshly because of the criminal intentions associated with them.

Washut made a motion to change the crime of vehicular homicide from a misdemeanor crime to a felony, but that motion failed.

Rep. Barry Crago, R-Buffalo, made a new motion, which later passed with a mixed vote, for an enhanced penalty option for felony punishments when the vehicular homicide occurs in a crosswalk or school zone.

The enhanced penalty option would not replace the existing misdemeanor option; prosecutors would have the discretion to evoke the enhancement as needed.

Rep. Karlee Provenza, D-Laramie, had spoken against the enhancement, saying she was concerned the state would give families the impression that victims who died after collisions in crosswalks or school zones were of more value than victims who were struck elsewhere.