It was a damning revelation: wolf hunting outside of Yellowstone National Park had “altered pack behavior, damaged research.” The allegation came from Yellowstone National Park (YNP) biologist Doug Smith as reported by WyoFile’s Mike Koshmrl.

The article, which has since received widespread distribution, claims that wolf hunting outside the park has resulted in “highly unusual mating behavior” in the park’s wolf packs, and quotes Smith: “It’s broken apart the social structure, it’s messed with the hierarchy, and it’s actually produced more pups. Now this is a hypothesis, but this is what I would call an artificial stimulation of wolf reproductive capacity. By going in and killing them, you stimulate reproduction.”

I’m calling “bullshit” on that claim. Sorry to be vulgar, but my search for an adequate substitute couldn’t generate a better descriptor for those claims.

The WyoFile article correctly reported that a majority of the park’s wolf packs usually produce single litters.

But that has never been the case for wolf packs inhabiting Yellowstone’s northern range – the area of origin for most wolves shot in Montana’s wolf hunts that have caused such concern for Yellowstone officials.

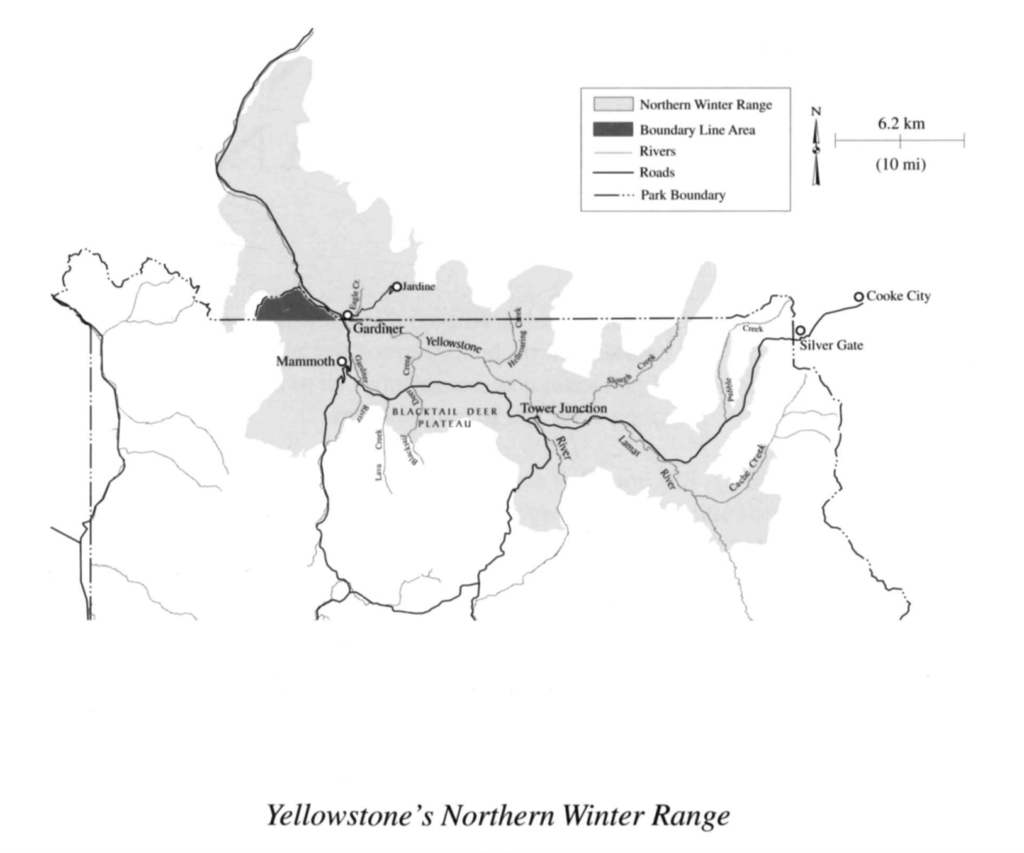

Although the northern range consists of only 10% of the national park, it has been the stronghold for the wolf population as it was once home to the biggest elk herd in Yellowstone.

Figure 1: Yellowstone’s Northern Range. Source: National Park Service

Multiple Litters Begin in 1997

Shortly after gray wolves were brought into YNP from Canada in 1995 and 1996, Smith was part of the team that documented multiple litters in individual wolf packs in the park, and Smith is the primary author of YNP’s annual wolf project reports.

In 1997, YNP documented 13 litters of pups in 9 wolf packs, with the Rose Creek pack having 22 pups in three litters, and the Druid Peak and Chief Joseph packs each producing two litters. All but the Chief Joseph pack inhabited the park’s northern range.

The next year, four packs had multiple litters, including two packs on the northern range. The year after that (1999), the Rose Creek pack had three breeding female wolves give birth to pups on the northern range – for the third consecutive year of multiple litters in this pack. In 2000, that pack did it again, as did the Druid Peak pack with its 21 pups born in three litters.

The park population peaked at 174 wolves in 2003, with 7 packs crowded onto the northern range, and the Druid Peak pack once again produced two or three litters of pups. Then the population started its downward trend.

By 2010, Smith and his wolf team wrote that the park wolf population had declined to 97 wolves, “a decline that was brought about by disease and food stress, and suggests a long-term lower population equilibrium for wolves, especially on the northern range.

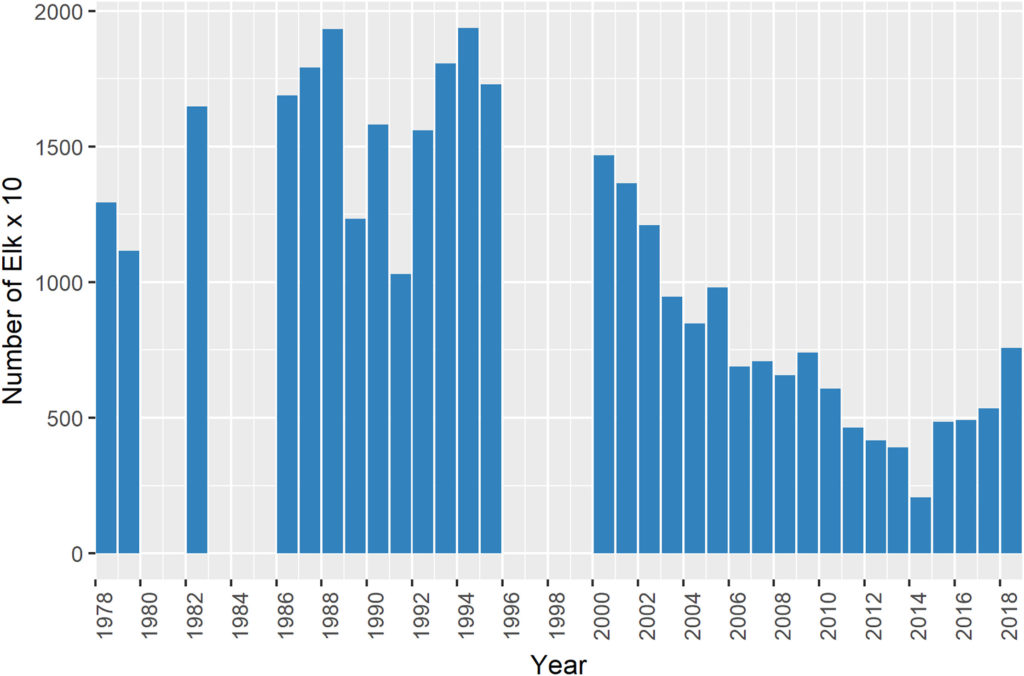

Northern range wolves have declined 60% since 2007 compared to a 23% decline for interior wolves during the same period. Northern range wolves are much more dependent on elk as a food source, whose population declined 70% since 1994, than are interior wolves that prey on elk and bison, both of which are still widely available in the park interior.”

Figure 2: Number of Northern Range Elk, 1978 to 2018. Source: Mossley & Mundinger, Rangelands (2018).

YNP’s annual wolf reports revealed that wolves killing other wolves accounted for most natural mortalities, but mange and distemper were taking their toll as well. With the decline of the overall wolf population, existing packs on the northern range declined, but those territories were soon taken up by the formation of new packs.

In 2012, Smith wrote that wolf hunting outside the park had resulted in the deaths of 12 wolves that lived primarily within the park, but park wolf packs produced smaller litters of pups – the opposite of his current claim that hunting outside the park increased pup production.

In 2016, Smith and two co-authors wrote about multiple litters on Yellowstone’s northern range wolves by explaining, “This phenomenon is believed to be influenced largely by Yellowstone’s prey abundance, wolf density, and more complex pack structures containing multiple, unrelated, opposite-sex pack members.”

Junction & Wapiti packs

In the recent WyoFile piece, Smith specifically noted there were multiple pregnant females in the Junction and Wapiti packs this year, suggesting it could be due to the mortality caused by hunting. But the annual reports Smith writes have reported that these packs both have histories of repeatedly producing multiple litters.

The Junction Butte pack produced four litters of pups each year in 2018, 2019 and 2020, and had multiple litters prior to those 4-litter years. The Wapiti Lake pack, which has shifted its territory to the west of the Junction Butte pack, has had multiple litters each year since 2017.

If these wolf packs have multiple litters again this year, it’s perfectly in keeping with not just their pack histories, but with the history of wolves that have used the northern range since wolves were released in the park more than 25 years ago.

Twenty years ago, it was the Druid Peak and Rose Creek wolf packs that inhabited the northern range and repeatedly produced multiple litters. “Wolves also took advantage of the favorable conditions in YNP by having multiple litters per pack,” Smith wrote in a book published more than a decade ago, noting that in 2000 the Druid Peak pack produced 21 pups in 3 litters, “increasing their pack size to 37 wolves and making them one of the largest wolf packs ever recorded.”

That’s Not Science

Rather than trying to cast the production of multiple litters as an abnormal behavior that is caused by hunting as Smith is now doing, just two years ago, he told a different story.

In the 2020 wolf report Smith wrote, “The prevalence of multiple litters in wolf packs in YNP (~25% of packs annually) has varied little over the last two decades. Large, socially-complex packs, higher wolf densities, and food abundance are believed to influence the prevalence of multiple litters and may partially explain this year’s increase.”

That report – dated just two years ago – noted that the production of 18 pups in four litters in one year put the Junction pack’s “exceptional size” at 35 members.

Rather than the “highly unusual mating behavior” he now claims it to be, Smith and his colleagues inside the park had documented this behavior on Yellowstone’s northern range, year after year, for decades – and specifically in the two wolf packs he cited in the article.

The Science

While Smith attempts to recast the cause of multiple litters in the Yellowstone wolf population, science doesn’t support his claims – and he knows it, since he writes the annual reports on wolf research and monitoring.

What is interesting is what appears to be a pattern of the park’s wolf population numbers increasing and peaking, before falling into decline, only to start the cycle again. The peak-and-decline indicates that when the park’s wolf population reaches a certain point, the habitat is saturated and the population will soon fall – with increased competition for a limited amount of prey, wolves will lose condition and will themselves fall prey to a variety of ills, from mange and diseases, to wolves killing their own.

An Idaho researcher examined the characteristics of multiple breeders in the wolf populations in Central Idaho and Yellowstone and suggested: “The occurrence of multiple breeding individuals varied considerably by group and year, but density was a strong predictor of the prevalence of multiple breeding females. Such a finding suggests that breeding opportunities are limited in this species and when they are, females may resort to polygamy. … Choosing to remain in groups and share breeding opportunities when density is high implies the habitat is saturated.”

Driven by Desire

What is the public to make of this altered story coming from YNP? I conclude that it’s purely politics, driven by Yellowstone National Park officials’ desire to create public pressure to change wolf hunting policies of state wildlife agencies in neighboring states.

If Yellowstone’s northern range is saturated with wolves, and more of those wolves range into Montana where the wolf population remains 6-8 times larger than recovery targets, Montana should just sit back and let Yellowstone decide how the state should manage its wolves? I don’t think so.

That thousands of people line up daily along the roadsides in Yellowstone to watch human-habituated wolves and bears, while park officials claim they manage for “natural” conditions, is at the heart of controversies involving predator management in states adjacent to the park.

The National Park Service has created this mess but points the finger of blame at state managers. I’ll go into that in Part Two of this series next week.

Cat Urbigkit is an author and rancher who lives on the range in Sublette County, Wyoming. Her column, Range Writing, appears weekly in Cowboy State Daily.