Anyone who has lived in Wyoming for any length of time has no doubt seen a print of a James Bama painting.

A portrait so vivid, capturing the essence of the subject’s mood, that one wonders if it might be a photograph. The subject, usually a cowboy, is looking away from the artist, who has finely detailed the person’s clothing and accouterments.

That was Jim Bama’s style in his later years, and is a large part of his legacy.

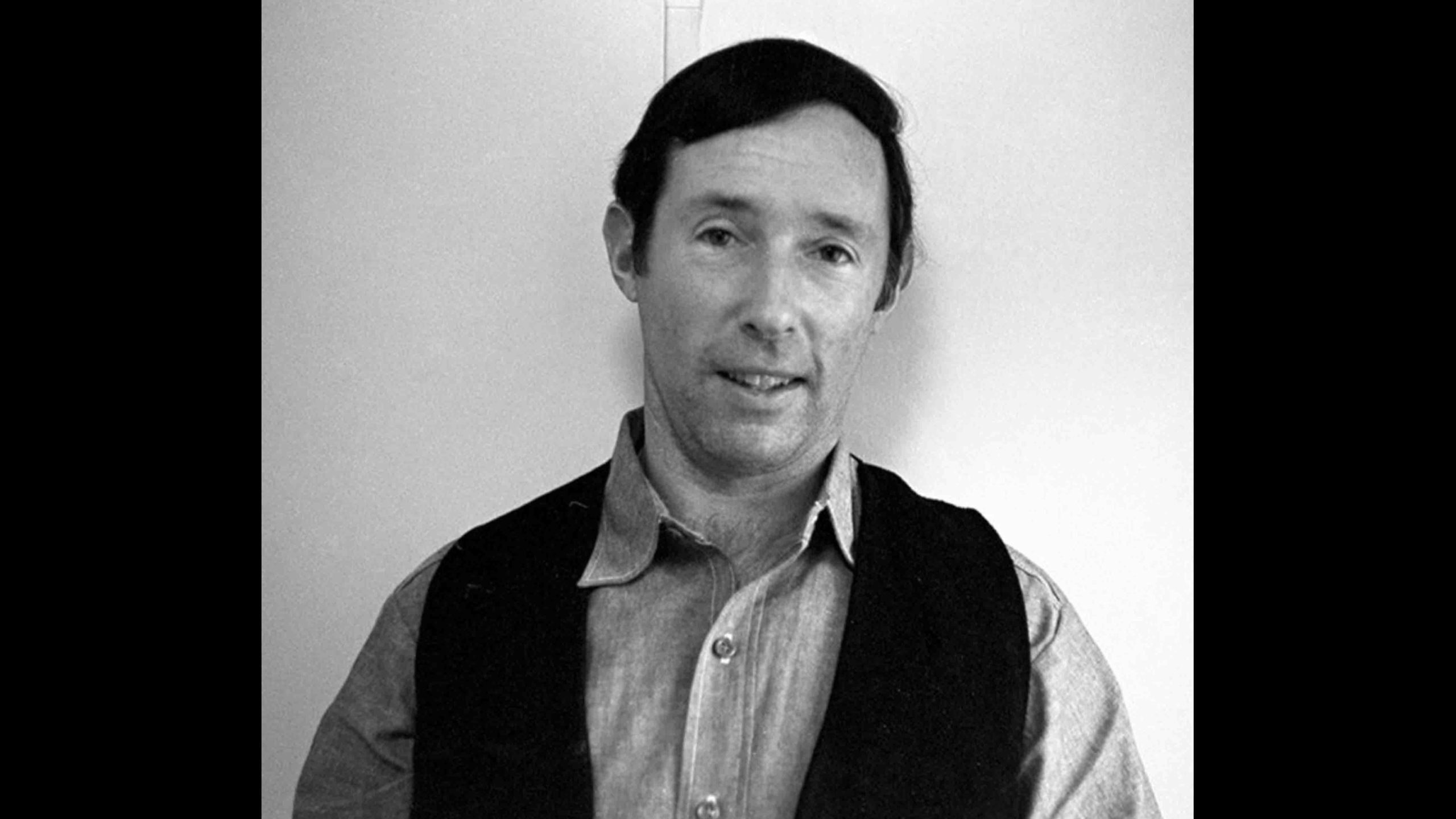

Bama passed away on April 24 at his home in Wapiti. He was 95 years old, and leaves behind scores of art pieces that have stood the test of time.

Bob and Nancy Brown, owners of Big Horn Art Gallery in Cody, told Cowboy State Daily that ever since they entered the Cody art world 35 years ago, Bama stood out to them not only as a legendary artist, but as a generous and genuine man.

“When we first thought about moving to Cody, they were doing an event at Old Trail Town, and Jim was there and Bob Edgar was there,” Nancy said, referring to the creator of “Old Trail Town” and the subject of one of Bama’s most famous pieces, “At the Burial of Gallagher and Blind Bill.”

“And as someone very new to the potential art world, I was absolutely in awe of this artist that could paint so photogenically,” she added. “Physically, yes, but just so graphically, and capture so much through that, and I think that’s what people responded to in Jim.”

Western art wasn’t always Bama’s calling card. When he first began selling his work at the age of 15, Bama was an illustrator.

In a 2014 interview with Robert Deis, Bama recalled his first paid job ($50 for an aerial drawing of Yankee Stadium for “The Sporting News”) and how his dream was to be a cartoonist, like his first hero, Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon). After his discharge from the army in the 1940s, Bama attended art school on the GI Bill, which led him into a career as an illustrator.

Bama was the illustrator for the entire 62-book “Doc Savage” series as well as multiple covers for men’s magazines in the 1950s and 1960s.

He took his own photos (over 55,000 of them) that he based his drawings from, and used various mediums depending on the work.

“For the men’s adventure magazines, I worked with fast-drying, water-based paints on illustration board because of the deadlines,” Bama told Deis. “My paperbacks and fine art paintings were almost all in oil. When you work in oils, the paint is thick and you work on a textured surface. When you work in water-based paint, the paint is thin and you work on an illustration board, which is smoother.”

With his wife, Lynne, whom he married in 1964, Bama moved to Cody in 1968, where his career as an illustrator for magazines and book covers phased out and a new phase of his artwork began – the realistic portraits he took of men and women in the west.

“I’ve been taking pictures out here for almost 40 years,” Bama told Deis in 2014, “and I’ve got a record of all the old-timers: a guy who drove a 24-horse steam stagecoach, the oldest living Arapaho Indian, who was in Tim McCoy’s Wild West Show and performed in front of Queen Victoria and was in the silent movie ‘Covered Wagon.’ I caught a lot of these people when they were in their 90’s. And Robert Yellowtail, who was a famous Crow Indian Chief. I got them not only in my artwork, but in the photography.”

It was Bama’s western art that hooked Bob and Nancy Brown in the 1990s.

“When he moved here he was completely enraptured with the West,” said Bob. “He’d grown up watching movies, and cowboys were pretty impressive. He never considered himself a Western artist, he didn’t like that title. He saw himself as an American realist.”

“When he got here, he was just mesmerized by the people, the characters, and the stories that they told,” added Nancy, “and he could do a really fine job of telling stories through his paintings, and through the people he painted. And I think that’s part of what made him so successful and what people responded to, because otherwise it’s just a portrait of somebody you don’t know.”

Several books have been released on the subject of Bama’s work, one of which was titled “American Realist” and was compiled by Bama himself and Brian Kane and released in 2006. Other compilations include “The Western Art of James Bama,” (1975); “James Bama: Sketchbook,” (2010); and “James Bama: Personal Works” (2012).

“Certainly, of his contemporaries, he was right at the very top of the ladder for that, just the very top,” Bob Brown pointed out. “And if you look back at those artists who have done well, in the last 40, 50, 60 years, most of them were artists who had a career in illustration prior to being involved in Western art full time.”

Because Bama didn’t see himself as strictly a western artist, he employed his realistic style to other subjects, including people he photographed while on a cultural exchange trip to China in 1987.

“He would probably not have been tickled to have been lumped in with other Western artists, because what he did, in his mind, was different,” Bob said. “He was capturing people.”

The Browns spoke of Bama’s love for his wife, Lynne, whom Nancy said was “the love of his life.”

“She really sacrificed her own career (as an author),” Nancy said. “She kept writing, kept producing things, but her career didn’t flourish in Cody. They truly loved each other and it’s a great example of how that relationship can work.”

Bama’s generous spirit was his defining characteristic, the Browns said.

“As high status as he does have in the world of American realism and Western art, he was really a humble guy,” Nancy said. “Very down to earth. He would just as soon stand and talk to the grocery cashier as to (noted artist) Howard Terpning. It didn’t matter. He was very humble that way. He was a fine man, and an iconic artist.”