Sometimes we must walk each other to life’s end.

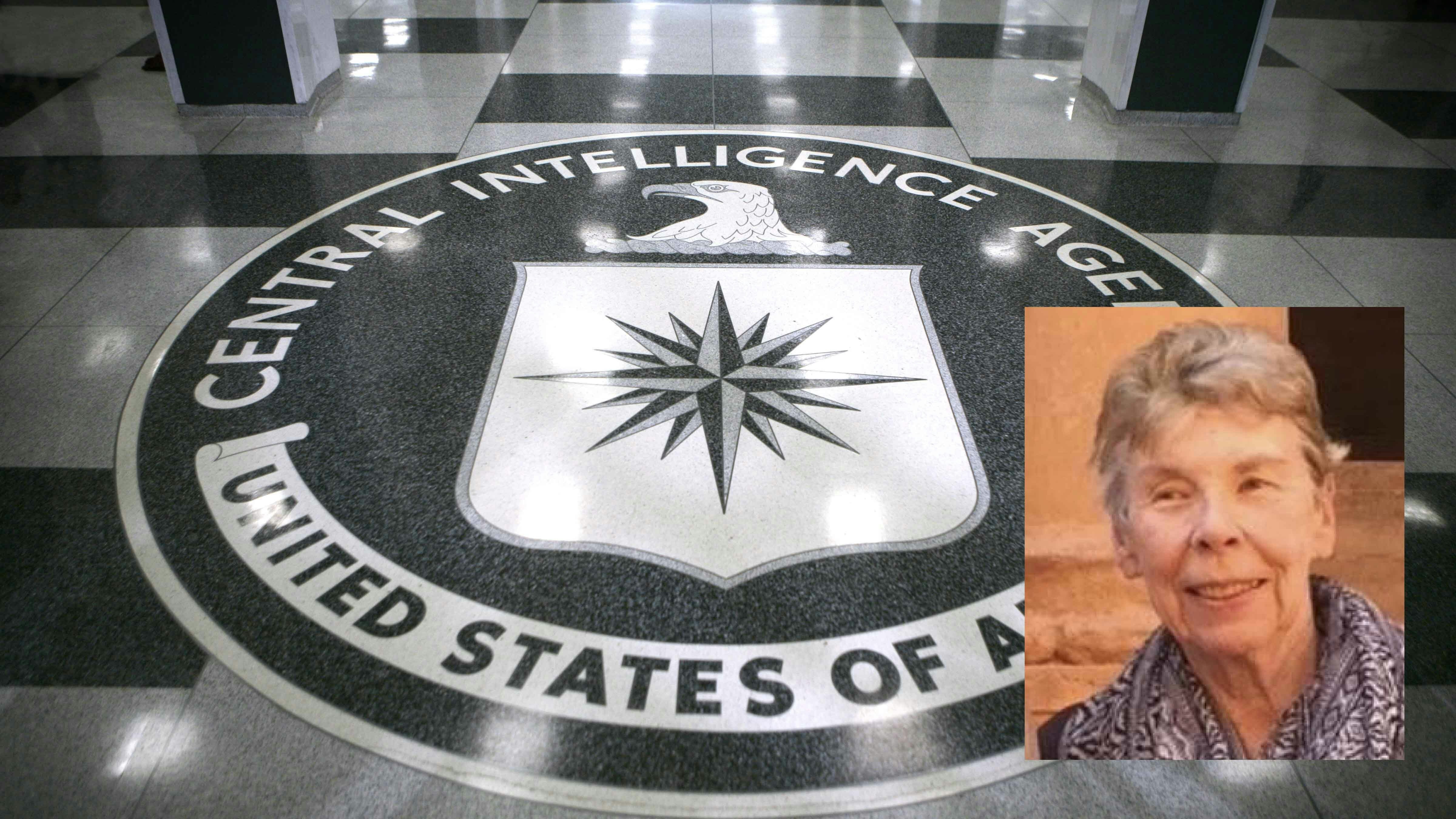

That’s the philosophy of Liz Lightner, of Lander, an end-of-life “doula” since 2020, who helps the terminally ill prepare for death.

“I try to reframe the entire experience people have, sometimes, toward the end of life, from a ‘scared’ experience to a ‘sacred’ experience,” said Lightner.

A doula is usually defined as a woman who provides guidance and support to a pregnant woman during labor.

Lightner’s job is similar, but on the opposite end of life’s spectrum.

A hospice volunteer for nearly a decade, Lightner encounters death often. She knows how to hold a hand, sense a need, and interact gently with someone whose faculties are slowly shutting down.

While hospice-style care is part of being an end-of-life, or “death” doula, a longer, more active phase of Lightner’s work is helping others plan for death while they still can.

“You’re working, ideally ahead of time, to figure out what people’s wishes are,” she said.

That includes helping people have needed conversations with doctors, family members, and with themselves early on, so the act of dying itself is less hectic.

“And when you talk about it, you enjoy life a little more,” she said. “You realize, we have a finite period here. What are we doing with it?”

‘So You’re Not Left With Guessing’

Most end-of-life preparations aren’t things people think about during their normal routines, Lightner said. And they range from trivial to crucial.

Choose a healthcare proxy, or decision-maker.

Designate a legacy contact to memorialize your Facebook page after you’re gone, or arrange to have the page deleted.

“We have a digital life,” said Lightner. “Each of us probably has at least 20 log-ins and passwords” to accounts that, without some planning, won’t be allowed to pass away when their owner does.

Confer the knowledge of a house’s secret workings – gun safe combinations, gas and water shutoffs, small maintenance habits – onto a spouse who’s staying behind.

Make farewell videos, legacy recordings. Get your “legal ducks in a row,” Lightner said.

Decide whether, facing an irreversible vegetative state, you’d like to be kept on life support or pulled from it.

Document your burial wishes. Plan your ideal funeral.

“Have those conversations you want to have – need to have,” said Lightner. “Sometimes the question is, ‘is there someone you’d like to talk to before you die?’ Talk to them.”

Lightner said empowering others is a large part of her role as doula. “I empower people to have those discussions… so you’re not left with guessing.”

A Funeral Someone Might Not Even Want

The average traditional funeral costs between $7,000 and $10,000.

And these are funerals that a loved one who has died “might not even want,” said Lightner, emphasizing the value of planning ahead of time.

“We’re thinking ‘well, we want to do what’s the best,’” she said. “And maybe there’s some guilt associated with it,” prompting survivors to buy the best casket or the best tombstone.

“Whereas, maybe if the person was asked, they’d just say ‘cremate me and put me in the Popo Agie River,’” she said.

There are “all types of body disposition” from which to choose, said Lightner, including casket burials, aqueous or flame cremations, and green burials.

In a green burial, the deceased is not embalmed and entombed, but simply, “put in a shroud and laid in the ground.”

Death Is ‘Not a Medical Emergency’

After the planning part comes the dying part.

Lightner said the three stages following a terminal diagnosis are the “shock phase” of initial surprise and reconciliation, the “stabilization phase” of cognizant planning, and the “transition phase,” which is the act of dying.

As a longtime acquaintance with death, the doula is meant during the transition phase to be a calm and comforting presence for both the person dying and the grieving family.

Lightner strives to educate the family on “what’s normal,” she said. “Breathing changes, skin color changes; temperature changes,” she said.

All the things that would shock onlookers if they weren’t already expecting a mortal parting.

“There are some family members that don’t want to let go – and there are some dying people that don’t want to let go,” said Lightner. “How can we make that more peaceful?”

One way is with visualization. Hearing is the last sense to leave us in death, Lightner noted, which allows her to “take people places” – by recreating their favorite experiences.

When sitting on a bedside with a person who longed for one last hike, Lightner described blue skies with puffy clouds scudding along, the scents of juniper and sage, the feel of the rocky terrain underfoot and the bracing stroke of mountain wind.

Though the practice is called “visualization,” it evokes all senses; the many scents, colors, sounds and textures of a journey worth dying on.

“It brings people back,” said Lightner, even as they forge ahead.

Though intended for those leaving us, visualization can be a gift for the living, Lightner added.

“I think it’s a lesson to all of us,” she said “to look around. Remember it.”

Beginnings and Endings

Much of Lightner’s care toward others is informed by her own experience with death and birth.

She joined the Peace Corps in the late 1990s in Togo, West Africa, giving maternal care and education and overseeing children’s activities.

“I miss the children and the simplicity of it all,” said Lightner. “And the respect for elders and family.

“(There’s) a pass-down of generation to generation that we’re losing here (in America), I feel like.”

Some of the disconnect between generations, Lightner theorized, has come about because American families can move hundreds of miles apart with ease, and don’t depend on each other as much to raise children and bring in food.

In poverty-stricken areas where communities bond together over every challenge and major life event, we are reminded that “it takes a village to raise a child,” said Lightner.

“It takes a village to help someone die, too.”