The widespread water system failures that shut down Rawlins schools and businesses last month could happen almost anywhere in Wyoming, according to a state water expert.

Mark Pepper, executive director of Wyoming Association of Rural Water Systems, told Cowboy State Daily that many of the systems bringing Wyoming residents drinkable water are old and in need of renovation.

Pepper said he hoped the infrastructure spending packaged approved last year by Congress would provide necessary funding to replace aging systems before it’s too late.

“Rawlins is not unique,” he said in reference to a series of events in early March that deprived Rawlins and Sinclair citizens of potable water. “You can throw a dart at a map and hit any (ailing water system).”

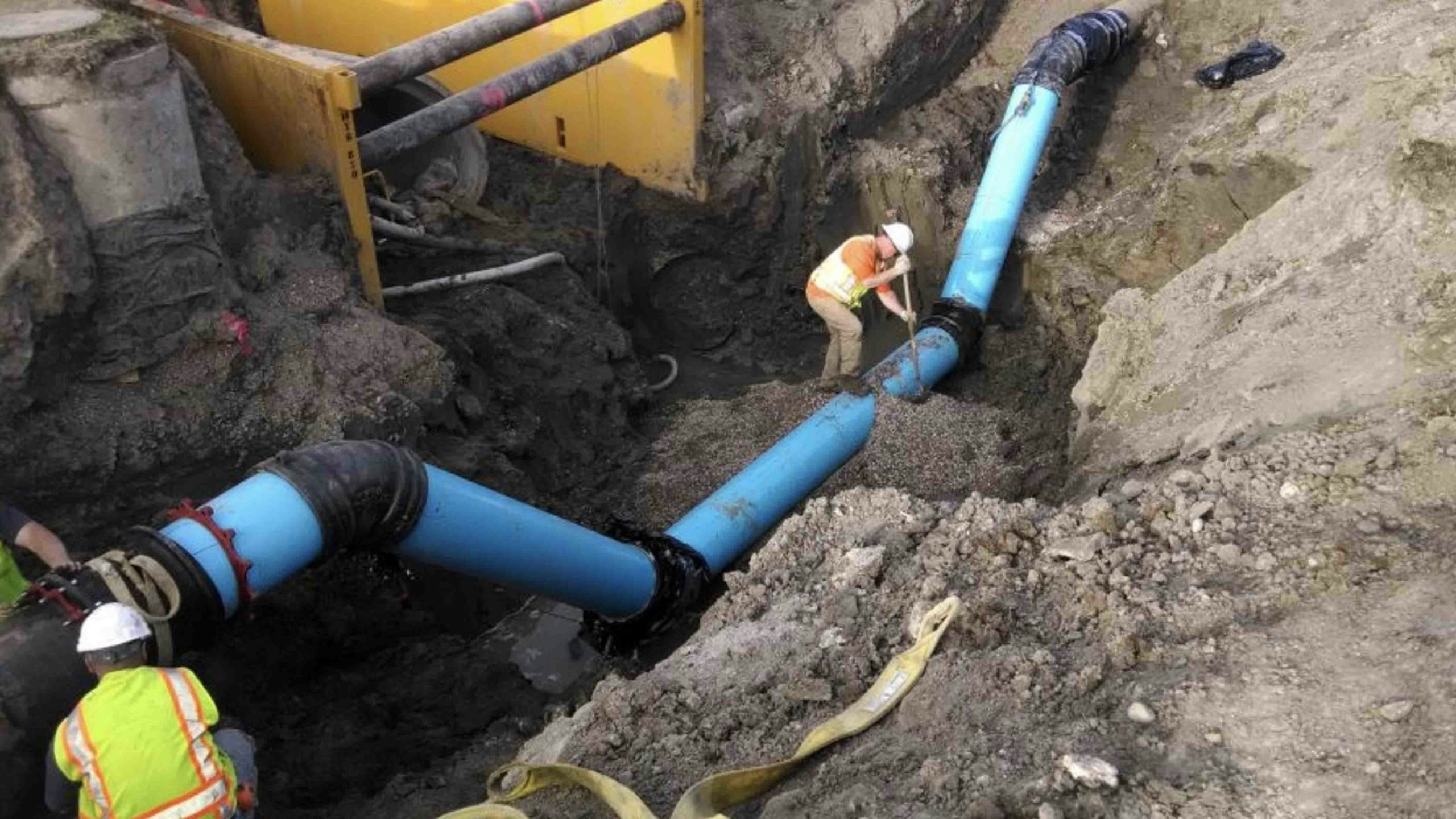

Rawlins had been repairing a 32-mile spring water transmission line since December and replacing its freshwater collection system, made of 108-year-old wood pipes, with PVC.

The repair process deprived the city’s water supply tanks of their usual freshwater influx, to the point of “barely making enough water” to meet citizens’ needs – a hazard that was prolonged by COVID-related supply shortages, according to a March 30 Rawlins water infrastructure report.

When the time finally came to turn the 32-mile spring line back on, a water line in Rawlins suffered what the report called a “full circle break” and allowed water to escape the system at three locations for more than seven hours, draining the freshwater tanks even more.

An integral part of the city’s water pumping system stopped working at the same time, prompting officials on March 3 to recommend that residents boil their water before consuming it. The recommendation was lifted on March 8 after two tests taken 24 hours apart showed no issues of concern.

Rawlins announced in the report that the city’s water is drinkable, but that residents can expect water restrictions moving forward. The city also said the repairs to water line breaks and other weak points in the system could take three to five years.

Since last summer, the report said, Rawlins already has identified multiple leaks, miles of corroded pipeline, faulty blow-off valves, an antiquated controls system, and a prevalence of 108-year-old wooden pipelines.

‘Perfect Storm’

Pepper called the simultaneous issues in Rawlins a “perfect storm.”

“Most water lines have about a 60- to 70-year useful life,” he said, but much of Wyoming “has very old, aging infrastructure.”

There are roughly 334 community water systems in the state, said Pepper, none of which can be fully funded with just consumer water rates. Of those, municipalities own about 96 and can apply tax funds “and whatever else they have in their general funds” to keep up with repairs.

The other two-thirds of those systems, owned by special and water districts and joint powers boards, “just have to rely on their rates and supplemental revenue” by accruing debts or applying for grants through organizations such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture or State Loan and Investment Board, Pepper said.

Community water systems, he continued, “have to be supplemented in some form or fashion” by additional funds – an obstacle that makes stockpiling money for a full replacement less than feasible.

The imminent delivery of state revolving funds for infrastructure upgrades, provided by a federal infrastructure package, Pepper said, are “going to be a Godsend.”

“It’s about triple the amount of money that typically comes to the state of Wyoming through the state revolving funds,” and should enable Wyoming entities to rebuild “a lot of our buried infrastructure,” he said.

The three- to five-year timeline to fix Rawlins’ and Sinclair’s systems, Pepper said, is realistic, “because Wyoming has a very short construction season,” and because “you’ve got to time (digging and replacement) so you don’t get too many people without water for too long.”

Supply chain shortages and inflation won’t hasten the already years-long effort, Pepper speculated.