Wyoming ranchers are used to weathering hard times. In an industry driven by weather and other conditions largely out their hands, agricultural producers are used to rolling with the punches and making do.

For ranchers in northeastern Wyoming, the last two years were hard. This year is shaping up to be even harder for producers who have already weathered two years of severe drought and skyrocketing prices for hay and feed.

Add in record-high diesel prices following a relatively dry winter and there’s not a lot on the horizon at the moment to be celebrated.

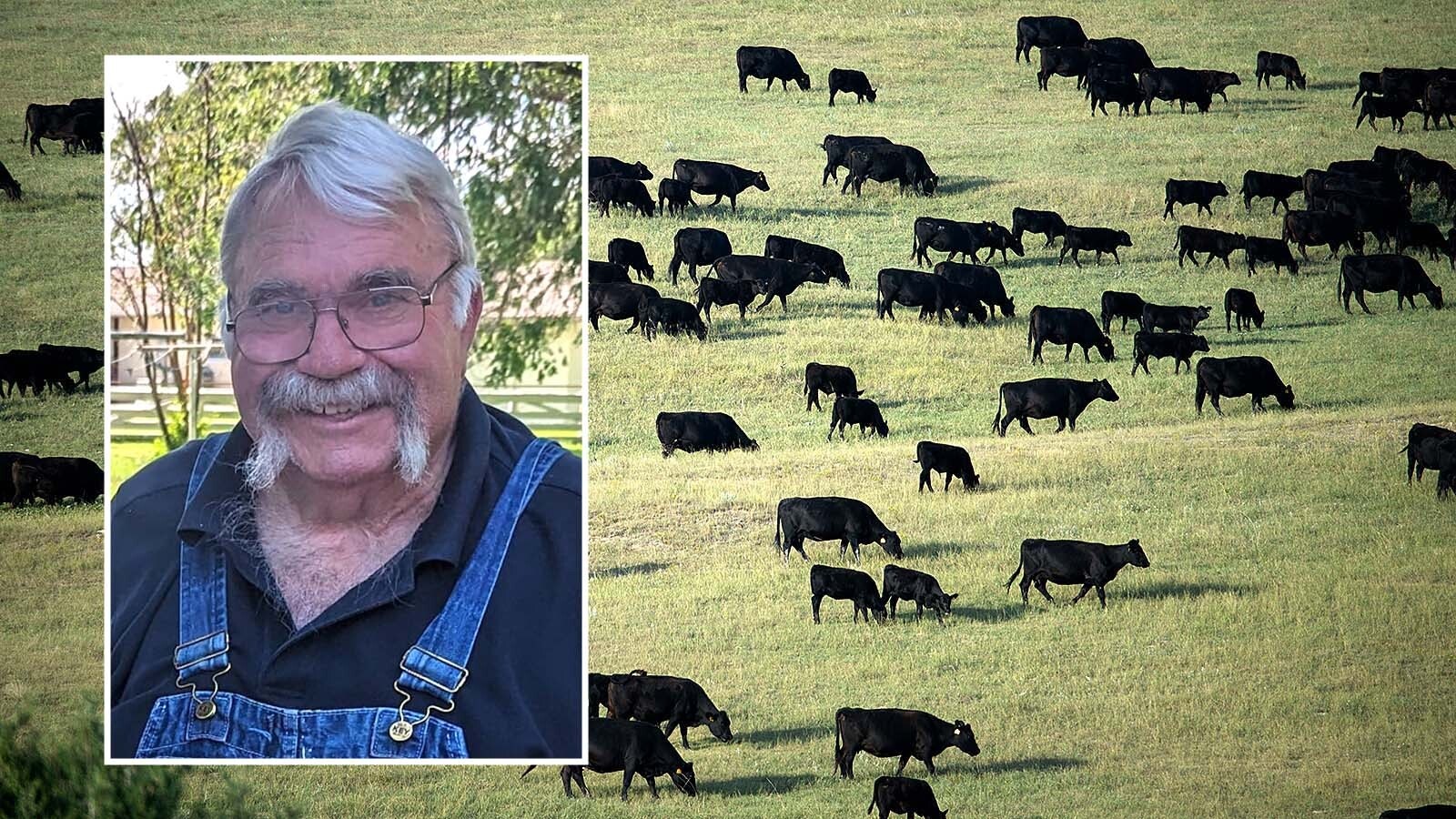

Shawn and Acacia Acord are steely eyed as they preview the season ahead. The reservoirs on the Faddis-Kennedy Ranch north of Gillette, which he manages, are dry, as is the riverbed for the Powder River running through the property.

Acord’s cattle have eaten most of the forage from winter range that had to endure through the last year so the rancher could cut back on buying hay at record prices. Everybody out here is pretty much in the same boat, he said.

“Everybody’s getting down close to the dirt,” he said.

It’s not just here in Campbell County, he said, but extends north to Johnson and Sheridan counties and into Montana.

Right now, the Acords are holding out hope to see some rain or snow this month and next to spur grass growth on their range. If no moisture falls, then the Acords will have to make some hard choices, whether that be to ship their cattle to a feedlot or sell them off early.

“We have nothing to feed, so when we try to truck food in, it’s just that more expensive,” Shawn said. “It’s not the trucker’s fault either. He has to be able to pay his bills, too. It’s getting to be too much.”

Other ranchers have already significantly reduced their herds to conserve pastures following last year’s drought conditions.

“It’s a major struggle right now,” Acacia Acord said. “We’re so weather-dependent, right? You can only do so much.”

Weather Outlook

The good news, said Tony Bergantino, acting director of the Wyoming State Climate Office and Water Resources Data System, is that northeastern Wyoming, including Campbell County, can expect to see anywhere from 1 inch to upwards of 1.5 inches of precipitation within the next week.

The bad news is that it might be too much at once, causing the water to run off rather than be absorbed into the soil, he said. Having the rain soak into the ground is important now because this is the time when grasses grow, he said, from now until around the first week of June.

Looking forward, he said the forecasts are not very promising for more rain ahead. Instead, he expects below-normal precipitation for April through June with above average-temperatures, very similar to last year’s conditions.

“Once we get past this next coming week, it’s not looking too optimistic,” he said. “One storm isn’t going to break a 2-year drought.”

Currently, Campbell, Weston, Johnson and Sheridan counties are experiencing an extreme drought, as are Park and Teton counties in the northwest.

If conditions hold, this will be the third year that the counties will see an extreme drought, an unprecedented development in recent years, Bergantino said, with the exception of shorter drought periods between 2002 to 2004, and more recently, in 2012 to 2013.

Low soil moisture in those areas also exacerbates problems caused by a poor snow season and the combination means entering the growing season with a moisture deficit, Bergantino said.

“Conditions start to stack up on you,” he said.

Tough Decisions

This is the time of year when many ranchers are holding their breath to see what kind of precipitation will fall between now and June.

“Only God knows that,” said Dennis Sun, publisher of the Wyoming Livestock Roundup.

The fourth-generation Central Wyoming rancher is hopeful that producers in the counties hardest hit by drought will see some relief, but without it, many will have to make some tough decisions.

For some, this might mean selling cattle or leasing grazing land in other parts of the state or in surrounding states. On average the cost for leasing land is about $30 a month per cow and calf pair, plus the expense to ship them to either to leased pasture or feedlots in Nebraska and elsewhere.

This third year of dry conditions is difficult, Sun said, noting that in the past, many producers in other states have shipped their cattle to graze in Wyoming and Montana during their own drought years.

“What makes it harder this year is that diesel is so expensive, and trucking (costs) are really high,” he said.

On a positive note, cattle prices remain high because cattle inventory has been going down nationally in recent months, which has raised the price of beef.

The downside for producers forced to sell off their herds is that it takes years to build back. In addition, they lose the genetics that they’ve spent years investing to perfect. Bringing in a new herd sometimes means starting the process over in addition to getting the cattle used to their new homes.

“They’re like kindergarteners, and you have to introduce them to the ranch,” he said. “They don’t do well that first year.”

Regardless, he said, Wyoming ranchers are used to weathering hard times.

“It’s not the first drought if you’ve been in the business,” he said. “They pop up about every 12 to 13 years.”

Everyone Impacted

A lot of ranchers in Campbell County have already taken out loans for hay, which began last fall, according to Justin Holcomb, market president at the Gillette branch of First Northern Bank.

Because people couldn’t put up their own hay last year, they were forced to buy costly hay to feed their herds through fall and winter.

The drought is probably the biggest factor impacting local producers, Holcomb said, as well as high input prices of diesel, fertilizer and the corn ranchers use to feed cattle when they get to the feedlots.

“It’s impacting everyone,” he said. “I don’t think there’s a silver lining.”

Holcomb’s bank has seen a huge demand for such loans, he said.

Holcomb runs cattle himself and is facing the same constraints and having to make the same hard choices of how to best recoup the inevitable losses brought on by this year’s perfect storm.

“One year is bad, and two years are terrible,” he said, “but three years are devastating and we’re about to enter the third.”

Relief programs

The United State Department of Agricultural Farm Service Agency has several programs in place to help Wyoming ranchers.

“They’re going to be hit hard again,” Todd Even, FSA program chief, said, noting there are several programs available to help producers throughout the state.

One is the 2021 Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP) that covers forage losses due to severe drought or wildfire this year.

A second is a new federal program launched by the agency on Monday, the Emergency Livestock Relief Program (ELRP).

This new $750 million program was signed into law as part of the Extending Government Funding and Delivering Emergency Assistance Act to help agricultural producers offset the impacts of drought or wildfires.

The programs, like others, are designed to help ranchers weather bad times, Holcomb said.

“The programs were never intended to make livestock producers whole, but rather help take the sting out of some of it,” he said.

Weathering Tough Times

Despite the tough times ahead, Acacia and Shawn Acord wouldn’t change their lifestyle for anything. Instead, they’ve figured out a way to make it work with Acacia’s full-time job in banking and Shawn’s secondary business training horses for Acord Quarter Horses.

Second jobs are nothing new for farmers and ranchers, Acacia said. Her her dad worked a full-time career “in town” while overseeing two ranches.

“This is the way of life we’ve chosen,” she said, noting that there many ranchers in the area have been through worse, such as the severe drought seen in the late 1980s, when the scorched land was teeming with grasshoppers and the fossil fuel industry was in a slump.

“Some will make it, and some won’t,” she said, “but the bright spot is the community we live in. We’re all in this together, and you can’t find better people than in the ag community. I wouldn’t change that for the world.”

Shawn agreed.

“Sometimes that’s all that keeps you going,” he said. “There are tough times, but there’s no better place to spend those tough times.