It was back in the 1980s that Deborah and Frank Popper published their “daring proposal” to reverse the settlement of America’s Great Plains by having the federal government purchase private property to create a Buffalo Commons they described as the “world’s largest historic preservation project, the ultimate national park. Most of the Great Plains will become what all of the United States once was – a vast land mass, largely empty and unexploited.”

“We are suggesting that the region be returned to its original pre-white state, that it be, in effect, deprivatized,” according to their essay published in Planning magazine. “{T}he government will take the newly emptied Plains and tear down the fences, replant the shortgrass, and restock the animals, including the buffalo.”

Thirty-five years later, the Bureau of Land Management’s approval last week to convert livestock grazing permits from cattle to bison to graze public lands in Montana sets the stage for the 21st Century version of the Poppers’ Buffalo Commons.

But instead of the federal government buying up private property to make a nature reserve, it’s the American Prairie Reserve, a non-profit Montana-based organization that has built up more than $100 million in assets since its founding about 20 years ago.

APR’s stated goal is to create the largest nature reserve in the contiguous United States. Although the nonprofit is located in Montana, that’s not where its money originated. Big business, big money, is funding creation of the reserve.

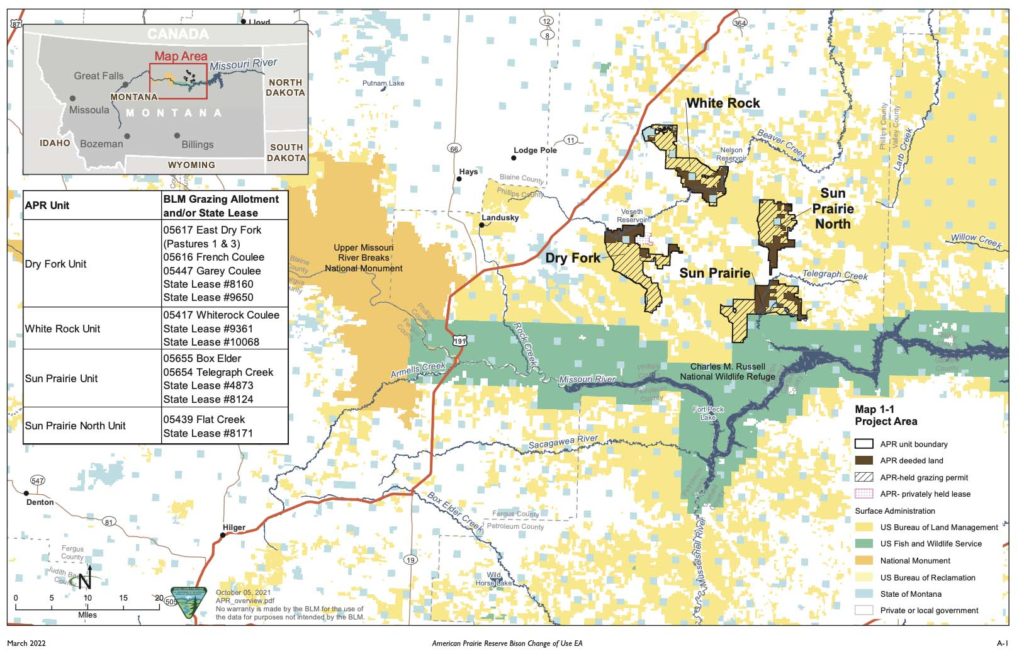

APR’s strategy is straight-forward: “purchase and permanently hold title to private lands that glue together a vast mosaic of existing public lands so that the region is managed thoughtfully and collaboratively with state and federal agencies for wildlife conservation and public access.” Through the purchase of private ranchlands, the group hopes to “stitch together” more than 5,000 square miles of public lands “in order to create a seamlessly managed wildlife complex.”

How does a large region of public land under multiple-use mandates of the Bureau of Land Management become a “wildlife complex?” Enter APR’s bison program.

When APR purchases a ranch, it also acquires the base property and associated livestock grazing permits for public lands administered by the BLM. Now the APR has convinced the BLM to convert those cattle allotments to bison allotments. That’s not unheard of – there are other grazing permits for bison use on BLM-administered lands in the Western states.

But those previous bison permits are for commercial bison production, which is livestock production. That’s not what APR is doing. They are running a “conservation” herd of bison– under a livestock grazing permit.

The BLM decision authorizes year-round bison grazing on three APR grazing permits, and seasonal bison grazing on three others. When the BLM authorized APR to switch from cattle to bison, that authorization used a 1:1 conversion ratio, meaning that for every cow permitted, one bison is now permitted. The decision allows for nearly 8,000 animal unit months of permitted use by bison.

The ironic part of this is that when the Taylor Grazing Act was enacted by Congress in 1934, it specifically stated that the purpose of the law was “to stop injury to the public grazing lands by preventing over-grazing and soil deterioration, to provide for their orderly use, improvement, and development, to stabilize the livestock industry dependent upon the public range, and for other purposes.”

The law provided for grazing permits to be issued with preference be given to landowners “engaged in the livestock business.” Does it seem APR is in the livestock business? Only if you warp or redefine that phrase.

APR isn’t engaged in the livestock business, and that will be at the core of the arguments that will surely wind up in federal court. The Taylor Grazing Act didn’t specifically define livestock, so the BLM issued regulations doing so, and those regulations define livestock as “Livestock or kind of livestock means species of domestic livestock – cattle, sheep, horses, burros, and goats.”

Those federal regulations adopted in 1978 authorized the BLM to issue “special grazing permits … authorizing grazing use by privately owned or controlled indigenous animals. These special grazing permits could be “issued at the discretion of the authorized officer. This use shall be consistent with multiple-use objectives.”

The BLM has decided it has the authority to authorize livestock grazing permits for bison as “indigenous animals” even though they aren’t used in livestock production. APR readily acknowledges that its bison are a “conservation herd” in which calves won’t be raised and sent to market for human consumption.

To control the population, APR will distribute some animals to other conservation herds, such as Native American tribes. Otherwise, APR allows hunting of a limited number of bison but refers to it as “public harvest” instead of public “hunting” – specifically because it views its bison as livestock (in order to get the grazing permits).

It’s bad public policy for those with deep pockets, enabled by a federal agency, to use their coffers to buy public policy. In this case, the BLM didn’t conduct an environmental review of turning a large portion of north-central Montana into a nature reserve, with a herd of bison at its core.

Instead, it did an assessment of switching livestock classifications on existing livestock grazing permits, knowing all the while that livestock grazing is not what is being done here. It allows the establishment of a bison herd on public land, complete with hunting – even though it’s called “harvest.”

The semantical gymnastics by BLM and APR remind me of former President Bill Clinton’s famous, “It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.” That’s certainly not an honorable or honest path to follow.

Cat Urbigkit is an author and rancher who lives on the range in Sublette County, Wyoming. Her column, Range Writing, appears weekly in Cowboy State Daily.