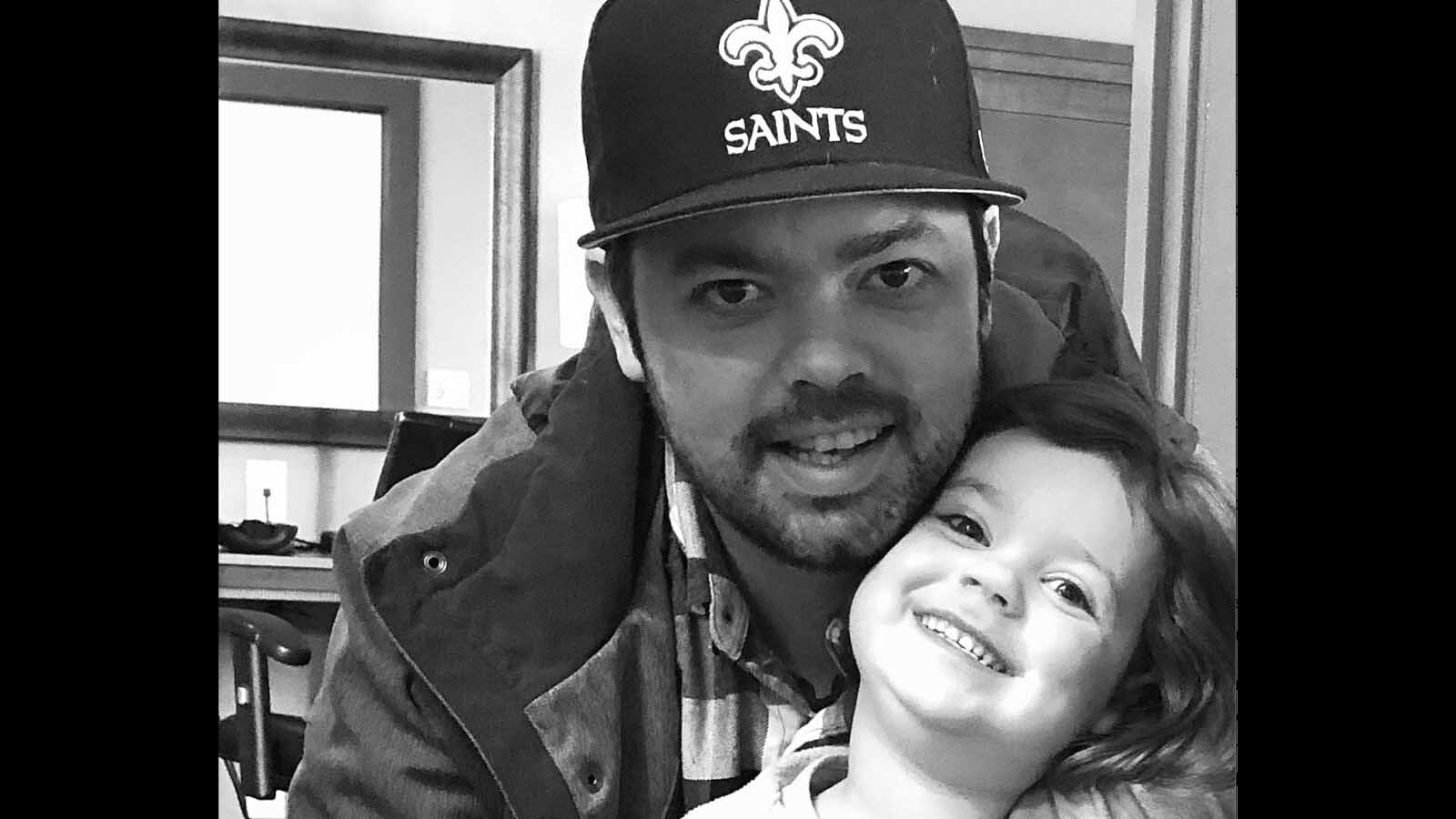

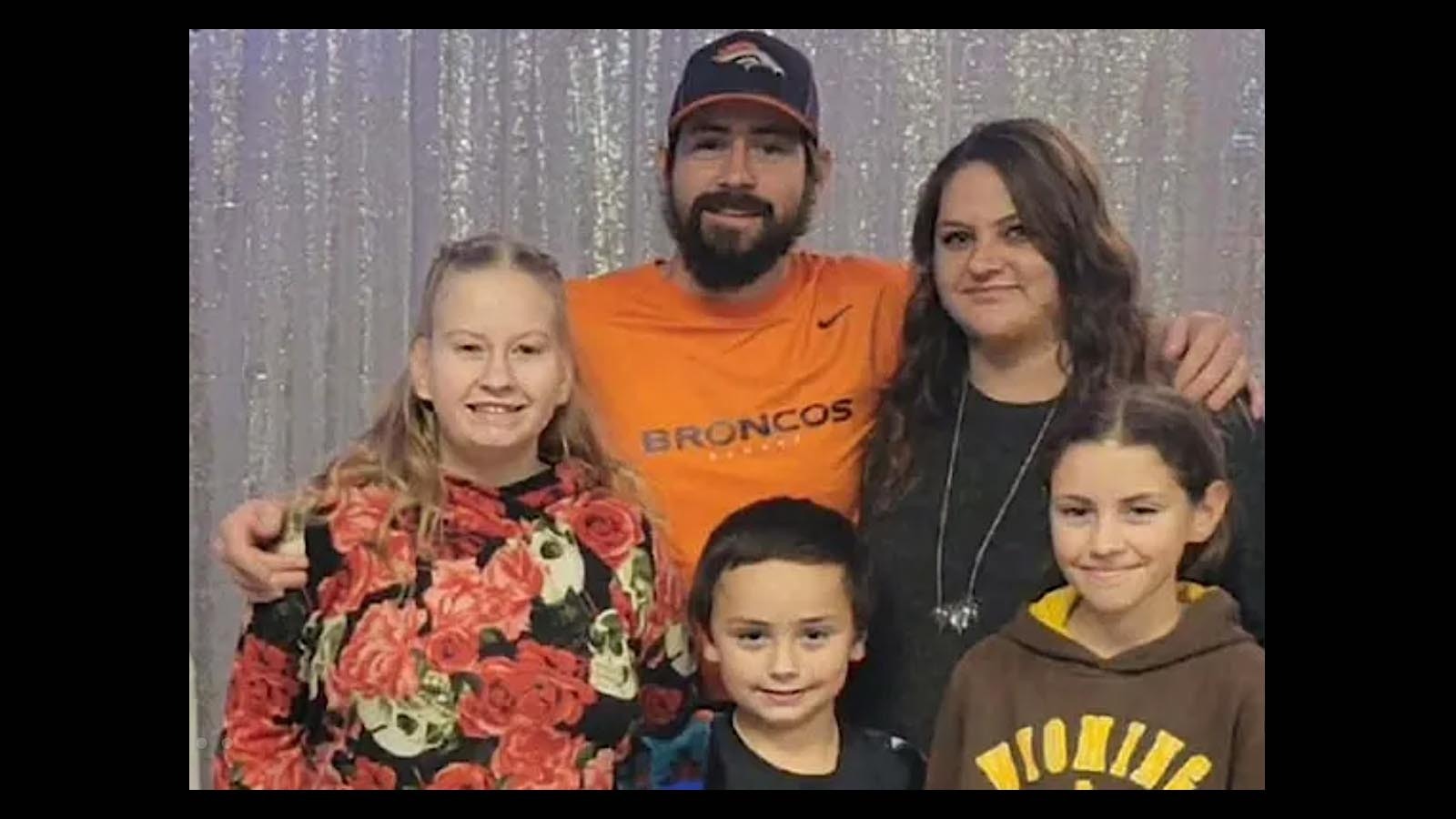

Tanner Wirfel was just 31 when he died from a fentanyl-related overdose in October.

His death — one of 45 fentanyl overdoses recorded in 2021 — is representative of the rising threat posed by the synthetic opioid, which state and federal officials say is rapidly increasing its presence in Wyoming.

According to Tanner’s mom, Tammy O’Grady, it was her ex-husband, Tanner’s dad, who got the ball rolling on his son’s addiction.

“He wanted to be a friend, not a parent,” Tammy said. “When you do that, you ruin your kids’ lives.”

To this end, his dad traded Tanner opioids from his cancer treatments for marijuana.

At age 18, Tanner ended up in rehab, which seemed to take hold. He was clean for 12 years during which time he got married, had a daughter and kept a good job.

Then a divorce put his life into a downward spiral as he once again turned to drugs to tune out.

The spiral didn’t last long, although Tammy remembers every painful minute. It started last Mother’s Day when Tanner was admitted to Cheyenne Regional Medical Center for a drug-induced cardiac arrest.

Tanner was ingesting both opioids and painkillers, and when he started taking meth, it caused narcotic psychosis that lasted up to several days at a time. Tanner’s house bore the scars from these periods of paranoia in which he felt that people were coming to get him. His entire personality began to change, and Tammy recognized the signs from his first round with drugs as a teen.

His next cardiac arrest was in June, and then every month after until his death in October.

After Tanner’s last hospitalization in August, Tammy begged the hospital to keep him one more day, so she could hire a lawyer and have him declared incompetent, so she could get him some help.

But the hospital considered him an adult under his own care and would release him within a day or two.

Tammy got a brief reprieve when Tanner was arrested for drunk driving following an automobile accident that landed him in jail for 33 days. Tammy did not bail him out, but rather left him there to face the consequences.

On Friday, Oct. 1, Tanner was released from jail and Tammy picked him up, warning him not to revert to his bad habits. He waved off her concerns.

That Sunday, while watching football at a friend’s house, Tammy tried to wrestle a pill out of Tanner’s hand, but he said it was just his prescribed anxiety medication.

After dropping him off at home after the game, the two made plans for their regular Monday lunch at Applebees.

That was the last time Tammy saw her son. When she went to pick him up the next day, the doors to the house were locked. She went home and returned later with a locksmith.

“I knew my son was dead,” she said, her voice choked. “A mother just knows.”

They found Tanner dead on the bathroom floor. The autopsy indicated a fentanyl-related overdose. He had 12 tiny, blue oblong pills in his pocket. Several of them were laced with the fentanyl that killed him.

“He would have never made it through (the pills in) his pocket,” she said.

Tammy is angry, she said, at the hospital for not keeping her son after that last cardiac arrest and for the lack of Medicaid funding to help addicts seek treatment, as they can in Colorado.

“The state doesn’t care about addicts and poor people without money,” she said.

She’s also angry at herself for not being more vigilant even though she was an “in-your-face mom” who did the best she could to keep her two boys out of trouble.

She is quick to warn other parents to be even more aggressive when it comes to keeping their children safe.

The state has an epidemic when it comes to drugs and overdoses, she said, and it needs to be taken more seriously.

“People don’t realize what it does to a family,” she said. “Parents are fighting for their kids every day.”

Skyrocketing Overdoses

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is sounding the alarm as overdose deaths involving the synthetic opioid fentanyl continue to climb at an alarming rate, for the first time topping 100,000 overdoses in the year ending this spring.

The DEA in recent months has also issued warning about the dangers of these counterfeit prescription opioids that are mass produced in labs by drug cartels, primarily in Mexico, and peddled as legitimate. Often, these drugs contain the wrong active ingredients or uncontrolled quantities of active ingredients as well as lethal amounts of fentanyl or methamphetamine.

Because the pills appear to be identical to legitimate prescription drugs, the user is typically unaware of their lethality, as in Tanner’s case.

Whereas prescription drugs are monitored by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), those bought on the street might contain any number of ingredients in varying amounts.

For this reason, it’s been hard for the state of Wyoming to track how many overdoses are related to fentanyl or other illicit ingredients, according to Guy Beaudoin, deputy state registrar for the Wyoming Department of Health.

As Beaudoin noted, until the state employs a better tracking system, it will be hard to truly understand how many people are dying of fentanyl or other drug-related overdoses.

Efforts are underway, however, to tackle this problem. Five years ago, the state incorporated new guidelines for reporting drug-related deaths, particularly when it comes to legal and illicit prescriptions, to try to get a better handle on how many people are dying of unspecified drug overdoses.

Even with the tighter reporting criteria, Beaudoin has been told from coroners that a further problem in zeroing in on these numbers is complicated by the way in which a body metabolizes the drug.

Regardless, given the numbers of overdoses reported in the last three years, there’s indication, Beaudoin said, that fentanyl-related overdoses are on the rise both nationally and in Wyoming.

“It’s not an epidemic yet,” he said, “but it’s concerning.”

Deaths are categorized as occurrent, in cases where a patient, regardless of their home state, was treated and died in Wyoming or residents of Wyoming who may have died in or out of the state.

In 2019, 11 Wyoming residents died from fentanyl-related overdoses, a number that almost doubled in 2020 to 21. The following year, this number more than doubled, increasing to 45 in 2021, with seven more possible overdoses reported already in 2022.

Breaking down the counties in which these overdoses occurred is complicated because due to closed record laws, the vital statistics department is unable to release to the public overdoses in any county where fewer than five deaths occurred.

In 2019, no Wyoming county had more than five fentanyl-related death.

Of the 21 fentanyl-related overdoses reported in 2020, Campbell and Laramie counties both had more than five, although the exact number remains confidential.

In 2021, Laramie County had the highest number of overdoses from fentanyl at 15, followed by Fremont County at 10. No other Wyoming county reported more than five that year.

The numbers are going up, Beaudoin noted, and the coroners are doing a very good job in helping identify overdoses.

Common In Wyoming

The first counterfeit drugs, including the small blue tablets stamped “M30” that closely resemble prescription oxycodone, first began turning up in Campbell County in 2018, according to Eric Small, a detective with the Gillette Police Department.

The drugs are likely being shuttled in by Mexican cartels who obtain the raw chemicals from China to cheaply produce the deadly synthetic opioid, Small said, which is mixed into many illicit drugs and sold to unsuspecting buyers.

Typically, law enforcement officers can look at a pill and detect that it is illicit based on its appearance.

As Small noted, fentanyl is 80 to 100 times more potent that heroin and deadly even in small doses. Because fentanyl is a controlled substance that can’t be obtained without a prescription, drug cartels are pressing it into pills in unregulated amounts because it’s cheap and highly addictive.

Small said fentanyl is becoming a huge issue and is being distributed in other narcotics such as methamphetamine.

Because the illicit drugs are not controlled, people have no idea what they are getting and in what amounts, hence the increase in overdoses.

“The amount of fentanyl in one pill can vary,” he said. “You might get a lot in one and a little in another. The significance in the amount will not be the same every time.”

It’s a dangerous thing, Small added, and is getting more popular particularly for people in their mid-20s to early 30s.

Natrona County, too, has seen an uptick in fentanyl use and overdoses, Natrona County Sheriff’s Office Investigation Sgt. Taylor Courtney said.

A lot of the times the synthetic fentanyl is mixed with a binder like acetaminophen — the active ingredient in Tylenol — that is mixed together and pressed into a pill. It’s becoming increasingly cheaper and more lethal, Courtney said, with the goal of being even more addictive.

The price, too, has dropped significantly, Courtney said, making it cheaper for users to procure.

Depending where a user is on the supply chain, one pill can run anywhere from $10 to $30, whereas a dealer may be paying $2 to $5 a pill, he said. Given the profit margins, distributors are moving massive amounts into communities.

Typically, the drugs are transported along the three major interstates to the larger cities that operate as a hub before being distributed throughout the network established by the cartels.

Unfortunately, Courtney noted, where there is demand, there will always be supply.

Societal Problem

One Narcotics Anonymous sponsor in Cheyenne, R.K., who asked to be identified only by his initials in keeping with the group’s rules regarding anonymity, said that every day he hears about someone dying of fentanyl-related and other overdoses all over the country.

“It really sucks,” he said.

R.K., who is a recovering meth addict who has been clean for 17 years, has been a sponsor to many in Wyoming and elsewhere. Some make it and others don’t, he said. It’s the ones who don’t who weigh heavily on him.

R.K. related the case of a Cheyenne man in his late 20s who died last year of a fentanyl-related overdose.

He said his acquaintance gotten hooked on OxyContin following a sports injury in college. Additional surgeries meant more pain relief. The doctors prescribed him opioids, and months later, he had a hard time getting off of them.

The man was “dope sick,” in the parlance of addicts, R.K. said, which the doctors also understood and cut him off from the drugs.

He then turned to heroin and was on the streets for two to three years before he joined NA and got clean. He’d been doing well, to R.K’s knowledge, and had been clean for about 18 months when he relapsed.

“What happened was he got an abscessed tooth and didn’t have dental insurance,” he said. “He went to doctor to try to get relief, but the doctor wouldn’t prescribe him anything because he was a former addict.”

So, the guy decided to take matters into his own hands and found some heroin, which was laced with fentanyl.

“That’s the thing about the streets,” R.K. said. “There’s no FDA saying you have to have clean drugs.”

Drug dealers are lacing products with fentanyl because it’s so addictive, he said. Increasingly, drug dealers are putting fentanyl in everything they sell from marijuana, heroin, counterfeit prescription drugs and cocaine.

Sometimes dealers purposely will give someone a laced drug, or “hot shot,” to kill them if they owe too much money or for other reasons, R.K. said.

The problem is that those taking the drugs want them so badly that fear of negative consequences isn’t an issue, he said.

The larger problem apart from unregulated drugs, he believes, is that addicts are not getting the help they need.

“Drug dealers and big pharma don’t care, and most don’t care,” he said. “In my opinion, it’s a societal problem. People look at drug users as the filth of the earth. Our system isn’t set up to help them. They go to prison or the mental hospital. The courts aren’t pushing people to go to anonymous programs. It’s a freaking disease.”