By Sam Lightner Jr.

It was my sophomore year in college, 1986, when the hook was set.

On veteran mountaineer Paul Piana’s advice, I’d gone on a quest to find a copy of the Bonney and Bonney book “Guide to Wyoming’s Mountains and Wilderness.” First printed in 1960, this cowboy climbers’ Bible was hard to find, so my buddy Bill Walker gave me his copy.

“You need it more than I,” he said. I raced home, ignored the necessary studying for a history exam (not that much to remember then as not too much history had passed yet), and opened the book to page 498. Randomly hit it, first try.

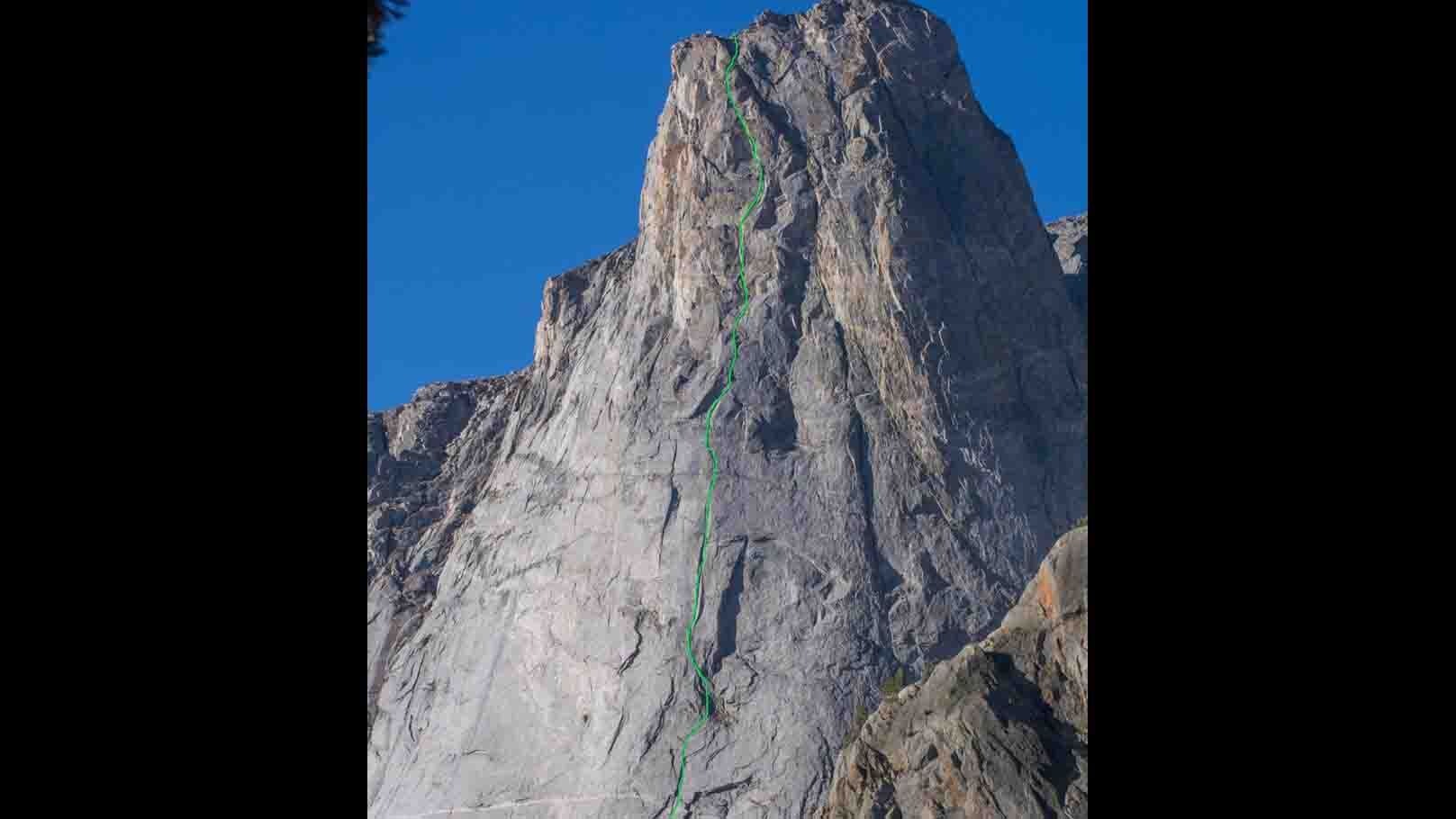

There on 498 was a striking photo of The Monolith, an 1,800-foot buttress of Big Sandy Peak, deep in the Wind River Range. It was an oddly shaped block of Precambrian granite with only one route to the summit, and that one route was not the one I would have chosen for the beautiful wall.

With a pen I scribbled in where I would someday go on the mountain, then spent the night paging through the tome of possible Wyoming adventures. I think I got a “C” on that 1986 history exam.

Flash forward 30 years, through dozens of countries and up hundreds of rock walls. Some small and some big, but none like The Monolith.

My friends Shep Vail, Mike Lilygren, and I had made it a yearly priority to climb something, anything, together. With wives, kids, businesses and mortgages, this usually meant something that took no more than a day, but that huge wall, which would certainly take multiple days to ascend, had never been forgotten. In 2015 we made a plan to go into the Winds and try the line I had scribbled into Bonney and Bonney decades before.

With a combined age well over the century mark, our Spartan days of sleeping wet and eating cold were behind us. We decided this trip would be treated like an international expedition, just one to a rock that was 30 miles from our bedrooms.

We hired Miss Jessie Allen, aka Miss Wyoming 2014, to haul in gourmet meals, individual tents with multiple sleeping pads and a half dozen gallons of bourbon, then convinced other friends to join us. One, Elyse Guarino, was willing to do so as our chef. From the shores of Papoose Lake in the Wind River Range, our trip in the mountains was going to be plush and soft . . . except for the climbing.

We made the 1,500-foot vertical walk from the lake to the base of the wall, which faces north and begins at 10,500 feet, the next morning and then began the climbing. “You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” was the adage on that trip, as we had not brought all the necessary big wall equipment needed for an ascent of the scale and altitude of The Monolith.

Too much bourbon, not enough rope. OK, not enough rope, otherwise fine. Dismayed after a week of work, we tucked tail and went home, bound and determined to come back stronger and with more rope the following year.

That year rolled around and Jessie again rolled our stuff off the mules and into Monolith Base Camp. This time we got very high, up to about 12,000 feet of elevation, but a band of bad rock had sent us back to the base.

We were actually in good fortune with that . . . had we topped out on the mountain that day in 2016, we would have had to spend the night there, and thus endured (or not endured) one of the most serious electrical storms any of us had ever seen in the mountains. The summit of The Monolith got pounded like Baghdad on a bad night.

No matter, we were coming back, but the following year we changed tactics. The bottom 1,400 feet of climbing was some of the best we had ever done, so the new goal was to make sure that future generations had a route open that was of exceptional quality.

Only being 300 feet from the top, less than two full rope lengths, the best way to do that was from above. We came into the mountains from the west, without horses, and went up the west slope of Big Sandy Peak. By the end of the trip we had found a route up the big wall that was exceptional in every way.

But there was still a problem; we had not completed the climb in the correct style. In modern rock climbing and mountain climbing, the goal is not to just get to the top, but to get to the top without using the rope for anything more than a safety net.

You are supposed to use the rock for upward movement, not the rope, but there was one section of rock so difficult we could not do it without resting on the rope. If the first attempt had been about “you’re gonna need a bigger boat,” this attempt was “you’re gonna need bigger muscles.”

The fact is one of us might have been able to free climb the crux, but we needed insurance. We needed something that could assure the clean ascent on the next attempt.

We needed youth.

Assuming we could not find a fountain that would provide it, we found someone who still had it; Alex Bridgewater.

Alex was then a 25-year old professional trainer on the cutting edge of difficult climbing in Wyoming. He was also a really nice guy with a witty sense of humor, and at 115 pounds soaking wet, he didn’t eat much. That combination made him perfect for this route.

The following season, 2018, we asked him to join us. Over a two-day period, our team managed to free climb all the hardest portions of the route. We were met on the summit by our chef in the first couple of efforts, Elyse Guarino, and all agreed to name the route “Discovery.”

The name came, in part, from the space ship in the movie “2001; A Space Odyssey” that is sent to research the Monolith, and in part from all we learned about the mountain and ourselves while climbing.

Discovery has since gotten rave reviews by the climbers who have gone into the Winds to find it. We are proud to have been able to find such a thing and open it up to others.

And I am happy to have finally put the dream to rest that started on page 498 in 1986.